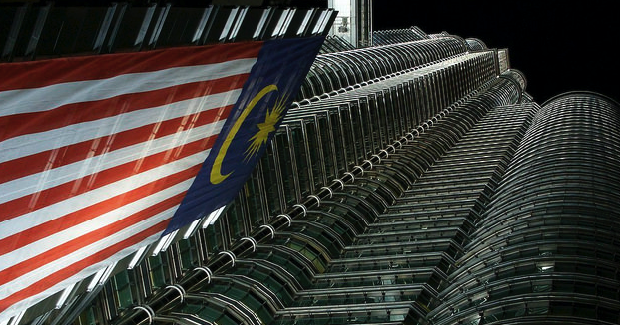

Malaysia: The Tangled Web of the 1MDB Scandal

Protests in Kuala Lumpur last weekend highlighted Malaysia’s ongoing 1Malaysia Development Berhad or 1MDB scandal. In July, the US Attorney General brought the outrage to a crescendo with the claim that more than US$3.5 billion belonging to 1MDB was “allegedly misappropriated by high-level officials of 1MDB and their associates” between 2009 and 2015. Although the case is officially closed in Malaysia, Prime Minister Najib Razak’s difficulties remain.

In 2015, evidence reported by The Wall Street Journal and individuals associated with the anti-government website, Sarawak Report, suggested that Prime Minister Najib Razak had received around US$680 million into his personal account. The Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission found that the money came from “donors” and disputed that the funds came from 1MDB. A complex series of foreign transactions obscured the ultimate source of the funds.Najib was officially cleared of any wrongdoing by Malaysia’s Attorney General in January 2016 despite news sources alleging that Malaysia’s Anti-Corruption Commission had privately recommended he face criminal charges. What does the scandal tell us about the global financial system?

Global financial institutions had key roles to play in constructing 1MDB’s edifice of debt. In 2014, questions were raised in Malaysia about the reported RM1.7 billion (US$476 million) in commission paid by 1MDB to Goldman Sachs in 2012 and 2013. An opposition politician called for an investigation into “the significantly higher than normal interest rates paid for the 1MDB bonds as well as the excess of 10 per cent “commissions, fees and charges” paid to Goldman Sachs International”. Two years later, the US Department of Financial Services investigation into the role played by Goldman Sachs raised questions about the due diligence performed by Goldman in connection with its bond sales for 1MDB between 2012 and 2013. Some of the funds raised by Goldman Sachs were transferred through the Singapore office of BSI—a Swiss bank that specialises in private wealth management services.Another institution to be implicated was the private wealth arm of the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), RBS Coutts. It has since been revealed that Swiss authorities were investigating client accounts at Coutts, which used to be part of RBS’s private bank. It is claimed that a number of other financial institutions were also involved in the web of 1MDB transactions.

Regulatory action extends beyond the United States. Singapore government authorities have seized assets worth around US$89 million from a colourful Malaysian deal broker, Jho Low. Singapore also laid charges of money-laundering against a former private banker who had worked for BSI. The Singapore operations of BSI have since closed, with the managing director of the Singapore Monetary Authority describing the bank’s behaviour as “the worst case of control lapses and gross misconduct that we have seen in the Singapore financial sector”.

BSI is also facing charges from the Swiss financial services regulator, FINMA. It has alleged that BSI “failed between 2011 and 2015 to identify risks around ‘dubious’ transactions totalling hundreds of millions of dollars involving ‘politically exposed’ persons”. Following the US government’s allegations in July 2016, Swiss police were reportedly investigating a former senior Abu Dhabi finance official over alleged attempts to embezzle money from 1MDB.

Official action has only come as a result of private individuals taking enormous risks—and paying a very high price. Xavier Justo, the former Swiss banker who leaked key information now languishes in a Thai prison. Xavier first made his explosive revelations privately in 2013 to Clare Rewcastle Brown—the key figure behind Malaysia’s Sarawak Report—who enlisted the support of a Malaysian media tycoon to publicise the story in 2015.

Regulators in global financial centres failed to take significant action when they were first made aware of potential problems. An insider had reportedly told the British authorities in 2008 that BSI was offering services that could facilitate tax evasion and money laundering. But the authorities took no public action over the financial-secrecy services that the bank was providing—and there was no indication that they took any private action.

In Singapore, the monetary authority had issued adverse rulings against BSI as early as 2011. They found “serious shortcomings” when they inspected the bank for a second time in 2014. They only closed its Singapore operations after another inspection in 2015 found “multiple breaches of anti-money-laundering regulations and a pervasive pattern of non-compliance”. By this time, the 1MDB case was making headlines around the world.

Mahathir Mohamad, Malaysia’s former prime minister, has criticised Singapore for not taking more robust action, claiming that the government of Singapore “is very reluctant to pinpoint the people involved in this corruption”. He also suggested that the reticence to act was motivated by its concern to maintain its reputation as a financial centre.

It seems unfair to single out Singapore when the problem is systemic in a world of globalised finance. As underlined in the so-called Panama Papers, the global financial system is one in which complex offshore financial deals by private individuals are routine. The line between perfectly legal tax minimisation and illegal tax evasion is blurred.

But there is a line. It is clear that the system is essentially designed to facilitate transfers which have the purpose of concealing beneficial ownership and reducing tax payments. This suggests that the problem is systemic rather than being a matter of a closing a few loopholes or bringing a few rogue bankers to heel.

Professor Natasha Hamilton-Hart joined the Department of Management and International Business at The University of Auckland in January 2011 after positions at the National University of Singapore and the Australian National University. Natasha is also the Director of the New Zealand Asia Institute. This article was originally published on 30 August by East Asia Forum and is republished with permission.