Mad, Bad and Dangerous? Australia in Chinese Eyes

Chinese people once regarded Australia as a friendly, safe, stable country with a beautiful natural environment and reliable system of law and government. Now, Australia-China relations have surely never been more critical.

Once upon a time, Chinese people regarded Australia as a friendly, safe, stable country with a beautiful natural environment and reliable system of law and government. No longer. In 2018, Chinese parents prefer Britain or Canada when considering where to send their children for education. Chinese scholars note that Australia has been involved in every war launched by the United States. Since they do not regard Donald Trump as a responsible leader, they think it quite likely that he could launch a military attack on China. In that case, they believe that Australia would side with America.

The biannual conference of the Chinese Association for Australian Studies in Beijing 21-23 June provided a venue for discussion of the current state of bilateral relations with over two hundred participants and a range of experts from both countries. Professor Zhang Yongxian of Renmin University, Beijing has been monitoring them relationship over many years. He placed three markers on the trajectory of its decline in the last decade, starting with Rudd’s speech at Peking University in 2008, when he said that Australia wanted to be a zhengyou or “true friend” to China. The term denotes someone who dares to point out mistakes even if this is jeopardises a friendship, so basically a critic. That a foreign leader would use such a term did not go down well with the audience.

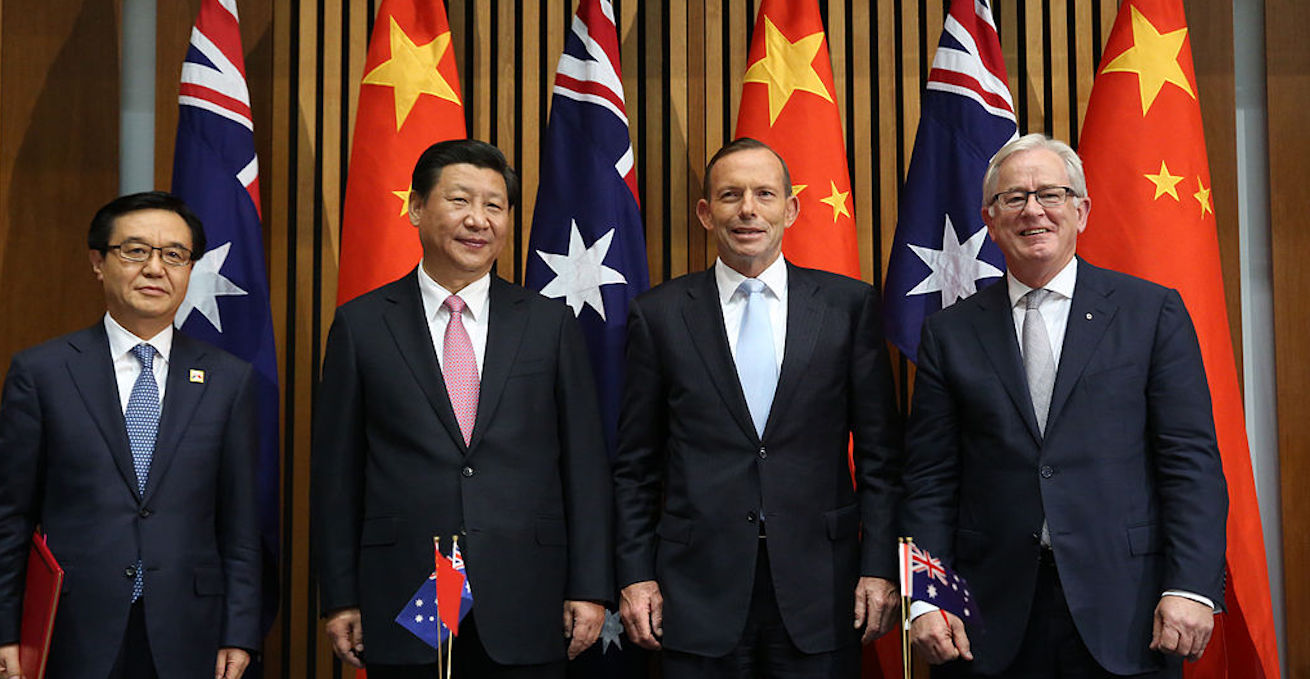

Next, Abbott told Japanese Prime Minister Abe in 2014 that he admired the skill and “sense of honour” of Japanese soldiers. To the Chinese, this remark apparently ignored the atrocities the Japanese inflicted on Chinese civilians during the Second World War. Thirdly, Turnbull said in 2017, using both English and Chinese languages, “The Australian people stand up,” quoting Mao Zedong’s words that originally marked the end of the Japanese occupation of China. To Chinese people, this clearly indicated that Australia regarded China as an aggressive power. They noted also that Turnbull and Bishop had both described the Chinese government as a “regime,” a pejorative term implying oppressiveness or illegality.

Quite a few Australian conference delegates gave their perspectives on the current state of bilateral relations. It was good for them to hear about the Chinese public response, particularly as Professor Zhang’s remarks did not touch on China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea or on Australian domestic security and political interference concerns.

Zhang added that he had several questions about Australia’s attitude to China that worried him. Why did the press accuse China of being lawless and unjust when CRA executive Stern Hu was sentenced to jail for corruption in 2010? How widely were the racist views of the One Nation Party shared by the Australian public? Were the two countries’ economies really complementary, as claimed by the Australian government? (The general view in China is that Australia is increasingly economically dependent.) Most Chinese people felt proud to host the Olympic Games in 2008 and loved its grand opening ceremony, so why was it interpreted by Australian journalists as aggressive and threatening? Was this and other reporting on China a negative reaction to the tightening of censorship?

Over the last week Turnbull and Bishop have tried to moderate the debate over the “Chinese threat.” Both turned out for the annual networking event of the Australia China Business Council in Canberra on 19 June. Bishop stressed that Australia’s Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with China was, in diplomatic terms, the highest level of a relationship between governments. She described that relationship as “robust … where we can manage our differences.”

Gerald Thomson, Deputy Head of Mission at the Australian embassy, elaborated further when speaking to the Australian Studies conference, stressing that Australia was committed to a long-term relationship with China and did not see China as a threat. He noted how broad and deep the relationship is and how many institutional links have been established, including between universities in both countries. While the US plays a central role in Australia’s prosperity and stability, Australia did not agree with everything, did not want a trade war and had told the US that it regretted their withdrawal from the UN Human Rights Commission. Thomson said recent tensions between China and Australia were “partly” due to Chinese actions and admitted that on the Australian side some messaging had been poor. He regretted that the relationship had become disconnected from its fundamentals.

Australia-China relations have surely never been more critical. However one looks at them, one must conclude that it is time that they were fundamentally re-set.

Professor Jocelyn Chey FAIIA was the founding director of the Australia China Institute for Arts and Culture at Western Sydney University, and visiting professor at the University of Sydney. She was previously the Australian Consul General to Hong Kong and was recognised as a Fellow of the Australian Institute of International Affairs.

This article was first published in Pearls and Irritations on 27 June 2018 and is reprinted with permission.