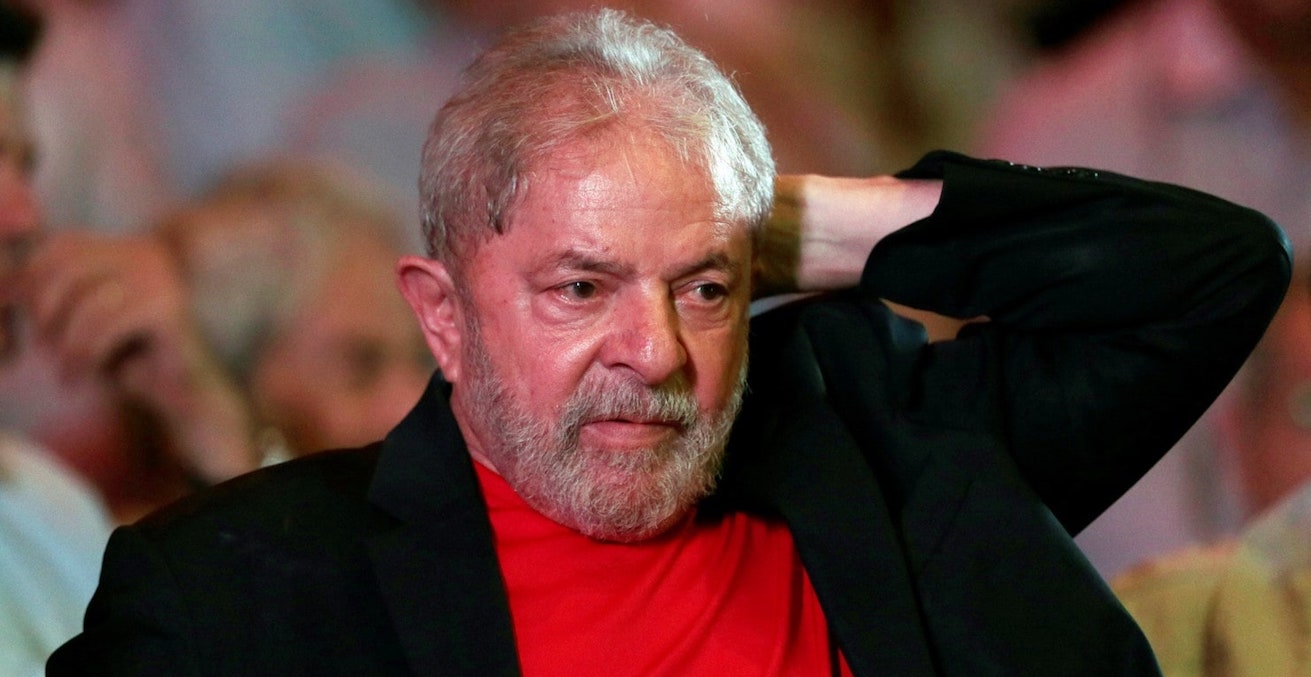

Lula Locked up and Brazilian Politics in Upheaval ... Again

Former Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva turned himself in to police on the weekend to begin serving a 12-year prison sentence for corruption. It derails his bid to return to power at this year’s presidential election and adds to growing instability in Brazil.

Former President, Lula da Silva, from the Brazilian Workers Party (PT), has been jailed for corruption, nepotism and mismanagement of public funds. He was found to be part of the Car Wash scandal that involved bribery linked to Brazil’s Petrobras oil company and has led to the incarceration of several other Brazilian politicians.

The contentious and dividing consequences of Lula’s imprisonment are enormous.

During Lula da Silva’s administration, Brazil’s economic boom was capitalised into his signature program, the bolsa familia (family allowance). This program was a conditional cash transfer providing a monthly stipend to low-income mothers to take their children to school and for regular medical checks. Some argue that the bolsa familia was an act of political demagoguery, but in 2012 it was heralded by the World Bank as a “new lesson to the world” on improving living standards for the poor. Indeed, between 2003 and 2012, poverty rates dropped from 40 per cent to 20 per cent

This is perhaps why, in spite of Lula da Silva’s condemnation, before he handed himself in to police, 47 per cent of Brazilians still wanted him to run in the 2018 presidential race. In fact, many of these supporters claimed that Lula’s trial was politically motivated to prevent him from running.

Looking back, the appointment of Michael Temer to succeed Dilma Rousseff in May 2016, indicated a conservative shift in Brazilian politics. Temer took office and with it took on the herculean job to deal with the administrative and institutional chaos. There were hopes that he would introduce pension, tax and electoral reforms to encourage business, private entrepreneurship, and to combat the endemic corruption that plagues the country. Regrettably, no reforms have been introduced and the modus operandi enabling the institutionalised corruption remains unchallenged. In fact, Temer has not appointed a single African, Brazilian or a female minister during his time in office. At one point, Temer was also being investigated in relation to the Car Wash corruption scandal, but his accusations have been frozen.

The matters which concern Brazilians most today are staggering levels of violence, endemic corruption and the current institutional crisis. There are fears that the institutional chaos and state of despair might create political momentum for an ultra-conservative and authoritarian uprising. In that regard, the recent assassination of human rights and LGBTQI activist, single mother and Rio de Janeiro councillor for Socialism and Liberty (PSOL) Afro-Brazilian Marielle Franco, created significant disquiet. Before her death, Franco publicly denounced police abuse in favelas and frequently vocalised her opposition to federal military intervention in Rio de Janeiro. Political commentators have pointed to this tension and the link between the nine millimetre bullets that ended her life and the bullets used by Brazilian federal police.

The federal military intervention increased federal powers over the state of Rio de Janeiro. It reminds Brazilians of past political trend when centralisation led to political authoritarianism and the suppression of democratic rights and freedoms. Franco argued that young black men living in favelas are greatly affected by police brutality and violence and that a military clamp-down will only increase murder rates by targeting the poor. Afro-Brazilian murders are approximately 70 per cent of Brazil’s annual murders, many of which are perpetrated by the police. Last year more than 1,000 were allegedly murdered in favelas in the state of Rio de Janeiro by police authorities. Franco’s assassination is a slap in the face of those fighting for the empowerment of women and people of colour in Brazilian society, and for human rights activists worldwide.

The Car Wash trials, Franco’s assassination and Rio’s military intervention could be symptoms of a more complex political scenario: a lean to the right where the political freedoms and the right to free speech enshrined in the 1988 Brazilian Constitutional Charter could be under threat. The assassination of Marielle Franco was received with shock by the international community, and is already creating tensions in the EU-Mercosur relationship.

Last week there were calls for the European Union to suspend trade talks with the Mercosur block. Additionally, the European parliament in coalition with 52 European representatives is lobbying the European Commission to suspend negotiations for a trade agreement with Mercosur until Brazil takes a serious stand on violence against political opposition, and particularly on those fighting for human rights in the country.

In a country marked by entrenched social inequality and racial divides, Lula da Silva’s imprisonment, the assassination of Marielle Franco and the federal military intervention in Rio de Janeiro might indicate a political trend which leads to political polarisation, confrontation and repression. Brazil is still a leading country in the region and a Latin American industrial hub, but political instability and the increasing popularity of ultra-conservativism and populism, raise fears that authoritarianism might be looming.

Flavia Bellieni Zimmermann is a sessional academic and PhD candidate with the School of Social Science at the University of Western Australia’s Centre for Muslim States and Societies. She is on the council of AIIA for WA and is a commissioning editor for Australian Outlook.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.