Money, Power and Muscles: Women in Nepalese Politics

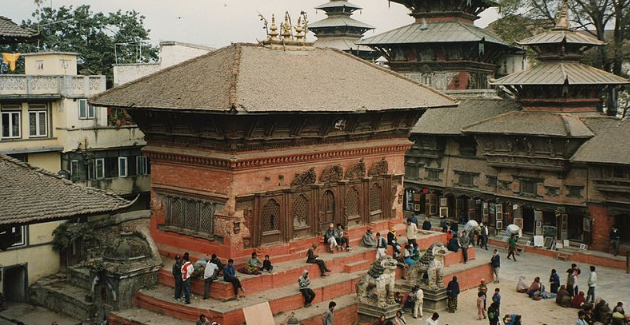

Voting in Nepal’s first local government elections in 20 years begins on 14 May. While women’s rights in Nepal have made significant progress since the 2006 Comprehensive Peace Treaty, considerable barriers to Nepalese women’s equal political and economic participation remain.

Nepal is undergoing its first local level elections since the suspension of local government in 1997 during the decade-long Maoist conflict. That conflict was about fighting structural discrimination based on class, ethnicity, language, religion and gender. Today, for the first time in Nepalese history, political parties must nominate at least one woman for major or vice-major positions at village, municipal and district levels. Further, two out of four seats on every ward committee must be filled by a woman and a Dalit woman. Otherwise, they must remain empty.

At the last local elections in 1997, women constituted just 20 per cent of candidates. This time, 40 per cent of representatives could be women—that is, 13,000 women, including 6,000 Dalit women. During the announcement of these historic elections, I was in Nepal to investigate how Nepal’s 2006 and 2015 peace agreements and 2015 constitution are being implemented and to what extent they have affected women’s political and economic participation in the post-conflict society.

Social science research shows that conflict transitions provide a ‘windows of opportunity’ for increasing women’s civic and political participation. At first glance, this is demonstrated in Nepal, where women were engaged in the conflict as combatants but were also adversely affected by it, including through sexual violence. How has this transformation period enabled or constrained women’s participation?

Women’s rights have come a long way since the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2006. Today, Nepalese women are more visible in society, defying gender norms that privilege men’s presence in public spaces. Historically, the proportion of women representatives had never exceeded 6 per cent. Today, many women from various backgrounds have become representatives in the Constituent Assembly (CA) due to the 33 per cent gender quota. Furthermore, women occupy the positions of chief justice, president and speaker of the CA. Some could write this off as tokenism. However, these women challenge perceptions of women in politics and leadership and have had significant policy impacts, such as contributing to the constitution-drafting process, advocating for greater levels of women’s representation and drafting laws such as the Domestic Violence (Crime and Punishment) Act of 2008.

Five recurring themes emerged from our interviews with civil society, government and international organisations in Kathmandu about the barriers women face in participating in substantive decisions in economic, political and social realms. First, we found that there is a lack of implementation of Nepal’s peace agreement in every day life, particularly in rural areas. This is not to say that progress has not been made, but participants expressed frustration that the status quo at the higher political level remains unchanged.

The second and related challenge to women’s post-conflict participation concerns patriarchal expectations for and constraints on women’s and men’s roles. Nepal is a deeply patriarchal society and nearly every interviewee identified patriarchy as a major impediment to women’s rights and participation. Patriarchy here refers to male domination and female subordination in both the private and public spheres. This hierarchy is characterised by norms and practices that are distinct for Nepal, such as Chaupadhi Pratha, a practice whereby women are segregated to cow sheds during their menstruation period. Other manifestations include citizenship rights (women in Nepal are unable to pass their citizenship onto their children) and inheritance rights (wives of disappeared men are unable to claim their property until 12 years have passed).

A third theme is the intersectionality of gendered oppressions and identities. This is not surprising, given that Nepal is made up of many castes and ethnic groups. Regional- and language-based identities affect women’s literacy rates, mobility, access to education and reproductive health. The research team called it an “onion of marginalisation” because of the multiple layers of discrimination experienced by differently situated women and girls and the interrelated nature of the issues they face due to gender as well as caste and ethnic inequality.

The fourth issue reflects gender inequalities in education and literacy as well as in life skills, such as confidence and experience, all of which constrain women’s potential to influence decisions. Women’s own self-perceptions and external perceptions of them by society reinforce their perceived lack of capacity for leadership and participation.

The fifth and final challenge relates to the burden of care faced by women, as in so many contexts around the world. In Nepal, the extra reproductive care roles women must perform include caring for dependents, household chores and collecting food, water and fodder. Furthermore, the growth of labour migration and increasing proportion of Nepal’s economy consisting of remittances have resulted in ‘female-only villages’. In these villages, women’s burdens are doubled if not tripled as they take on additional workloads.

These five challenges to women’s post-conflict participation in Nepal are interconnected and mutually-reinforcing. They hinder women’s participation as candidates, supporters and voters in these local elections. For instance, those we spoke to consistently emphasised the lack of resources, “money, power and muscle”, as a major challenge to women competing on the same level as men in election races.

Participants from women’s civil society organisations are especially concerned about the stipulation that women only need be nominated for candidacy: the actual major or vice-major posts do not have to be filled equally by women and men. They argue that political parties are nominating women only for the vice position or in districts where they have extremely slim chances of winning. Moreover, coalition government between parties could effectively put men in both leadership posts.

While women’s rights have come a long way in Nepal, dynamics around the current local elections, gender-inclusive quotas notwithstanding, reveal the enduring patriarchal attitudes and hierarchies that entrench women’s inequality. The outcome of Nepal’s local government elections on 14 May–14 June in which 19,332 women are contesting seats in 383 local levels across 34 districts will show just how far Nepal has come in realising women’s rights to participate in the governance of their post-conflict society.

Sarah Hewitt is a PhD candidate with the Monash Gender, Peace and Security Centre, working on the Australian Research Council Linkage Project, “Towards Inclusive Peace: Mapping Gender Provisions of Peace Agreements”, partnered with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.