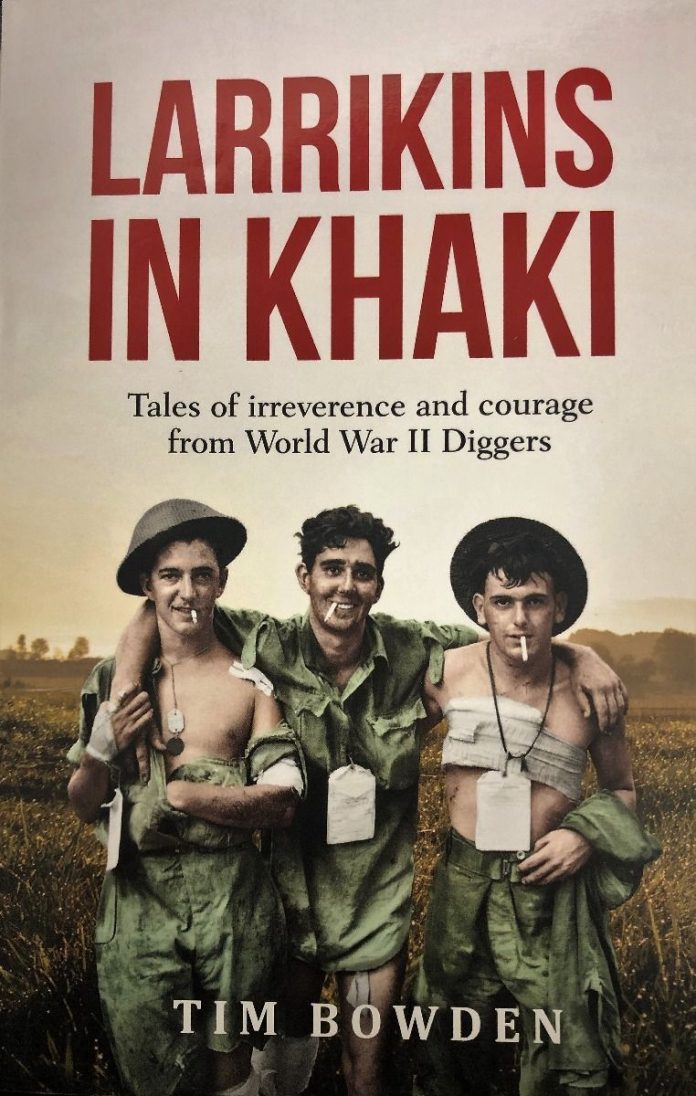

Larrikins in Khaki - Tales of Irreverence And Courage From World War II Diggers

Tim Bowden takes a compassionate yet irreverent look at the experiences of Australian diggers in World War II. Even today, it provides valuable perspectives into the lives of Australian service men and women.

Two diggers are leaning against the side of a trench, smoking and holding their .303 rifles in one hand. A senior British officer followed by a gaggle of junior officers pick their way briskly past them. The diggers don’t shift or salute. After the senior officer has passed, a junior officer spins around and comes back. “Don’t you know who that was?” The diggers consider the question. One answers “Nope. You ever met him Barney?” “Nah, not me.” Junior officer: “That was General Birdwood!” The first digger says, “Well he didn’t have feathers on his arse like any other bird would.”

That occurred on the western front during the First World War. But as Tim Bowden observes, Australian army humour was the same during the second great catastrophe, for which Australia, like Britain, was equally ill-prepared. Amid the tactical stuff-ups, and the puzzle of why fighting Italians and Germans in Egypt, Libya, Greece, and Crete was protecting Australia from invasion, the Australians developed a protective carapace of cynical humour.

The madness began in 1939 and 1940 at recruiting centres and drill halls in Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane. Cursory medical examinations and lax questions as to age allowed both unfit men and under-age youths to slip into the ranks. A dearth of modern weapons had men drilling at Ingleburn and Puckapunyal with broom sticks as rifles and gum trees as artillery pieces.

The madness continued as Winston Churchill and the British cabinet played their strategic games. After the fiasco of Dunkirk, their unwillingness to invade any part of Nazi-occupied Europe had to be justified by action elsewhere to prove to Roosevelt that Britain was taking the fight to the Axis powers. So in 1941 and 1942, the Eighth Army, of which Australian divisions were a substantial part, fought Rommel in Libya and German armies in Greece and Crete. The tide turned against Rommel in Egypt and Libya with an offensive that began in October 1942 at El Alamein. But Greece and Crete were lost.

Bowden lards his narrative with anecdotes about the digger’s contempt for authority, and his driving interest in alcohol and recreational sex. Typical was a 10-platoon man, Corporal Stan Montefiore, who had dined and wined too well at a roadside cafe in Greece. Staggering outside, he encountered Sir Thomas Blamey and his tribe of “shit-kickers” all riding by on horseback. Full of joie de vivre, Monty called out “How are you going Tom, you white-whiskered old bastard?”, an unusual greeting to a man who headed Australia’s army. Blamey reined in his horse and told a side-kick to “tear the stripes off that man and put him under close arrest.”

The diggers’ contempt might have been greater, however, if they had known of the cynicism with which Churchill moved Australian divisions around his strategic chess board, none of it directed at the defence of Australia. Unknown to the average Australian, Churchill had no capacity nor intention to honour Britain’s pledge to protect Australia from Japan from its naval stronghold in Singapore. His strategy, secretly shared with Roosevelt, was to defeat Germany first, and worry about the Far East second. In this scenario, Australia was considered expendable, to be recaptured when the tide of war turned in the Allies’ favour.

These priorities remained even after several military catastrophes occurred between December 1941 and February 1942. Japanese forces occupied Hong Kong and Malaya, and Japanese aircraft sank the Royal Navy’s Prince of Wales and Repulse, all in December 1941. Japanese ground forces then took Singapore with a force vastly outnumbered by the defenders in February 1942. Prisoners from Australia’s 8th division rotted ignominiously in Changi, or joined thousands of POWs and Asian conscripts assigned to build the Japanese railway from Kanchanaburi in Thailand to Thanbyusayat in Burma. Many in the work force were starved or beaten to death – a death for every sleeper. Many more would have died but for the courage and steadying presence of an Australian Army doctor, Colonel Edward “Weary” Dunlop.

But as Bowden recounts, even under such trying circumstances, the diggers’ rebellious spirit lived on. When a Japanese officer resplendent in ribbons, leather boots, and sword mounted a podium at Changi and ordered the assembled prisoners to toast the Emperor on his birthday with sake, there was dead silence. The officer repeated the order, accompanied by clicks as machine guns trained on the multitude were cocked.

Then out stepped Vern Rae, a rugged 15th Battery intelligence officer from Tasmania, who thundered out, “Boys, we will drink to the Emperor!” He held up his mug. “FAAAARK the Emperor!”

A great roar went up.

“The Emperor – FAAAARK the Emperor,” the assembly shouted as they quaffed their sake.

The Japanese officer then dutifully completed his toast “Ah sō … FAAARK the Emperor!”

Bowden briefly describes the well-known tussle between Churchill and Curtin about bringing the 6th, 7th, and 9th divisions from the Middle East back to Australia to face a feared invasion by Japan, and Churchill’s attempt to divert some of them to defend Burma instead. A soldier arrived in Sydney on 31 May 1942 just in time to witness midget submarines torpedoing HMAS Kuttabul in the Harbour. Bowden describes another digger’s anti-climactic homecoming after years of war in the Middle East:

Arriving at Devonport, Ivan (Ivo) Blazely was offered a lift home to Winkleigh by Claude, a sergeant and his wife who had picked him up at the dock. They dropped Ivo at a cross-roads about 100 yards from his family home at Winkleigh. Just as Ivo got out of the car, his old man came out of the house to collect the mail. “I thought that was you” was all he said. Sentiment never ran high in the Blazely family.

Bowden briefly sketches the soldiers’ re-training at such army bases as Pukapunyal and Canungra before being re-equipped and thrown into battle at Milne Bay and along the Kokoda Track to defend Port Moresby. Armed with mortars, Bren and Owen guns, as well as standard Lee Enfield rifles, they were better armed and equipped than the earlier Middle-East Force. But regular AIF soldiers regarded those drafted into the Citizens Military Force (CMF), the “chocos,” with contempt, until the chocos bravely acquitted themselves in desperate fighting in New Guinea.

Meanwhile, the diggers’ interest in alcohol remained strong. As Bowden tells it, a booze committee was formed in Bougainville and shareholders were acquired. Sugar was liberated from the battalion cooks, alcohol from range finders and compasses. Two 44-gallon drums were welded together and placed in a clearing hacked out of the jungle behind tents. The brew was left to ferment in the heat for a week. Canned blackcurrent juice was added for flavour and effect. The smell resembled that of a urinal at an Australian pub near closing time on a Friday night. The chief brewer, Slim, took a swig. His tongue shrivelled and he gasped “It’s ready.” The committee decided to trade some for Lucky Strike cigarettes with members of the US Marine Air Group 25. A Marine guard took a swig. His eyes bulged and he breathed deeply. The moonshine was duly delivered. The next night there was a riot in the Marine lines during which shots were fired and officers assaulted. The committee buried the remaining moonshine, laid low, and decided to abandon the liquor business.

Bowden accurately describes Australian actions in the last stages of the Pacific War as unnecessary. MacArthur had island-hopped his way up to Okinawa and Japanese garrisons from Borneo to Bougainville were cut off from supplies and literally starving. Yet MacArthur ordered Blamey to fight them and he did.

When the Japanese surrender followed the atom bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945 respectively, around 14,000 Australian POWs out of 22,000 captured by Japanese forces survived. Their homecoming was delayed and traumatic, resulting in enormous difficulty in adjusting to civilian life. In the closing chapter of his book Bowden shows great compassion for these challenged men. Larrikins in Khaki should be compulsory reading for all Australians interested in military history. It would provide a much-needed perspective about the challenges facing Australian service men and women involved in today’s undeclared and unreported wars.

Richard Broinowski AO was an Australian diplomat who served in Iran and several South East Asian countries. He was Ambassador to Vietnam, Republic of Korea, and to Mexico, Central American Republics, and Cuba.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.