K-pop May Be On a "Coronavirus Lockdown" But It's Unlikely to Slow Down for Long

K-pop is the South Korean phenomenon with a passionate global audience. The impact of coronavirus on K-pop is just another example of how the pop music genre sits at the intersection of performance, profit, and politics.

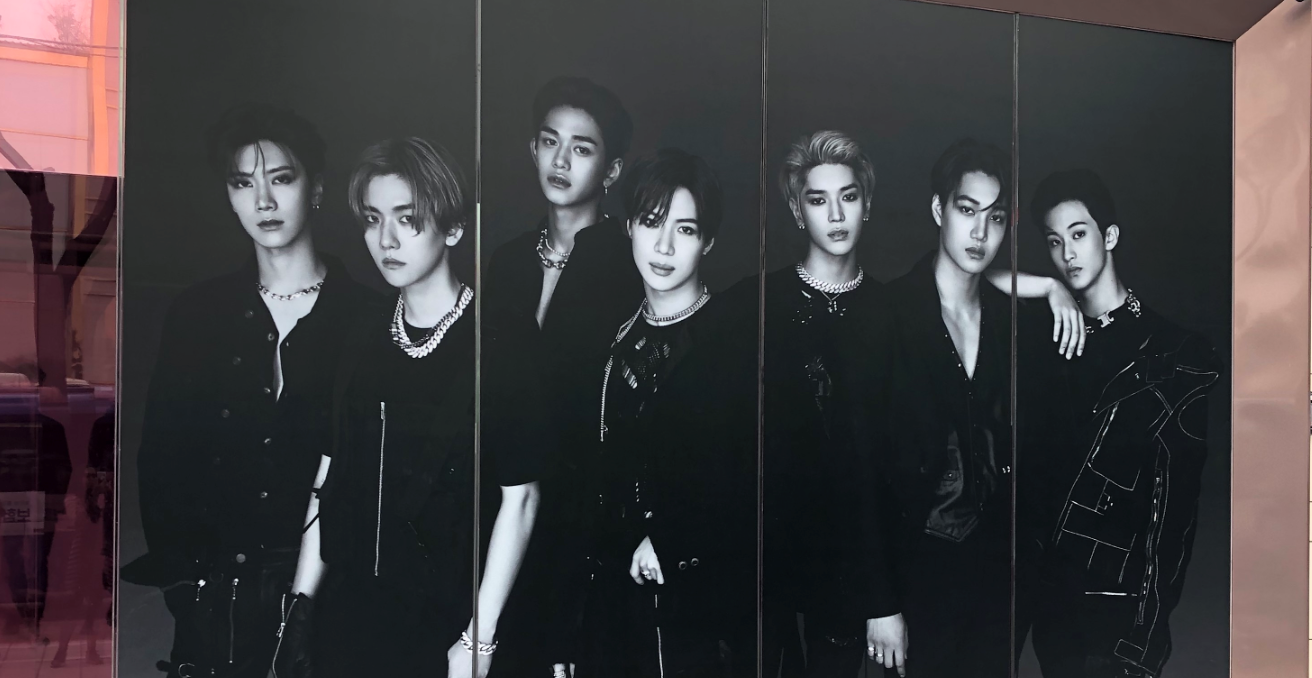

Across East and Southeast Asia, concerts and other fan-focused events that are a mainstay of K-pop have been cancelled or modified over coronavirus concerns. Popular boyband Seventeen cancelled its world tour, Big Hit, the entertainment agency that manages K-pop megastars BTS, stepped back from its plan to open its annual corporate briefing to reporters and fans, and major weekly music shows did recordings without live audiences. Genre veteran Super Junior postponed its Malaysian tour dates, while the group’s junior label-mate NCT 127 pulled China and Macau from its schedule of concerts, prompting Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post to hyperbolically declare that K-pop was on a coronavirus lockdown.

K-pop is a national entertainment industry which, more than any other, is supported by the South Korean government, making K-pop a fascinating exercise in soft power. Its association with South Korean cultural diplomacy, and its firmly-entrenched foundations in consumption, reflect commodity capitalism’s borderless appeal. The 2019-nCoV outbreak is not the first time the popular music industry has been impacted by developments far removed from the entertainment world. For example, in 2016, when Seoul incurred Beijing’s wrath by permitting the US missile defence system THAAD in South Korea, China’s economic retaliation included blacklisting K-pop, one of South Korea’s most lucrative and widely popular exports among young Chinese fans. Any K-pop fan can attest that ‘stanning’ (that is, closely following a particular group in the increasingly popular genre) is a process that involves far more than just listening to music. Like many other fandoms, the K-pop fandoms have a specific parlance and language, infighting between, and sometimes within, fandoms, “rules” that are fluid and, to an outsider, often illogical, and rampant, crazy consumption.

K-pop is spoken of in “generations,” with the earliest iteration of Korean popular music influenced by global genres such as rap and hip-hop, rock, and electronic music emerging in the 1990s. K-pop stars are referred to as ‘idols’, and idol culture began with boy bands amassing enormous, domestic fandoms skewing young – made up of teens and young adults. Pioneering members of K-pop’s first generation included Seo Taiji and the Boys, H.O.T, and solo idols like Rain, who were influenced mainly by Western hip hop and RnB. Like Japanese idols, South Korean ones were groomed and prepared with military precision (and often in military-like conditions) with lessons in singing, rapping, and especially dancing – with complex choreography performed with knifepoint precision being an integral part of the genre’s appeal. The end goal of the gruelling training and diet regimens was to maximise artists’ appeal – and profit-making ability – among the industry’s core markets – young, overwhelmingly female fans.

In the early 2000s, the so-called second generation of idol groups looked to new sources of revenue from potential fans overseas. At first, these second generation groups like Super Junior, TVXQ, Wonder Girls, and Big Bang set their sights on South Korea’s East Asian neighbours, Japan and China. Further expansion meant targeting ASEAN countries, where K-pop remains a tour de force today. These are also some of South Korea’s key trading partners, after the US and China. The second generation also helped K-pop to become popular in emerging markets in the Middle East (Super Junior was the first K-pop band to perform a concert in Saudi Arabia) and South America. The next couple of decades (2010 onward) saw the rise of the third generation of K-pop, with groups like the Chinese-Korean boy band EXO, who were lauded by the South Korean government and dominated the music scenes of various Asian countries.

This third generation also continued the tentative steps taken by second generation groups like Super Junior to recruit non-Korean idols. EXO began with four Chinese members, although three left citing discriminatory practices by entertainment company SM. Its sole remaining Chinese member, Zhang Yixing, has been prevented from performing or promoting with the group since the THAAD fiasco. An industry outsider, Psy, broke Youtube viewing records in 2012, and became the first South Korean winner of a Billboard Music award, with his maddeningly catchy ‘Gangnam Style’. The song contained a subversive message mocking South Korean society’s obsession with material wealth and consumerism – a theme explored in detail by Parasite, the 2019 winner of an Academy Award for Best Picture and the first non-English language film to achieve that honour. Finally – supported by its massive, loyal, and global fandom – BTS stormed the gates and led K-pop to even greater heights in the West.

With a blurring of the exact years delineating each generation, fans dispute whether the “third gen” is over yet. They do generally agree that it is undergoing its final laps. This is not the case with K-pop in general, which has become firmly entrenched as contributor to South Korea’s soft power and its economy. BTS alone is believed to enrich South Korea to the tune of more than four billion US dollars per year , making the boy band as valuable to the country’s bottom line as chaebols like Samsung or Hyundai.

Given its international reach, this attractive, addictive, and sometimes infuriating industry is bound to be affected by the shifting sands of bilateral relations and global epidemics.The domestic and global hurdles faced by the industry – the fraying of ties with China over THAAD, a sex scandal engulfing some key players, the suicides of idols, and outbreaks of disease – will be swatted away, and K-pop’s fourth generation of young men and women, with impossibly good looks, killer dance moves, and swoon-inducing voices, will invariably emerge.

Dr Nasya Bahfen is a senior lecturer in the Department of Media and Communication at La Trobe University.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.