Justice, Syria and the International Criminal Court

President Bashar al-Assad and members of his regime may soon face charges in the International Criminal Court. But there are significant hurdles that must be overcome to prosecute the crimes committed against the Syrian people.

This article was originally published on Australian Outlook on 13 March 2019.

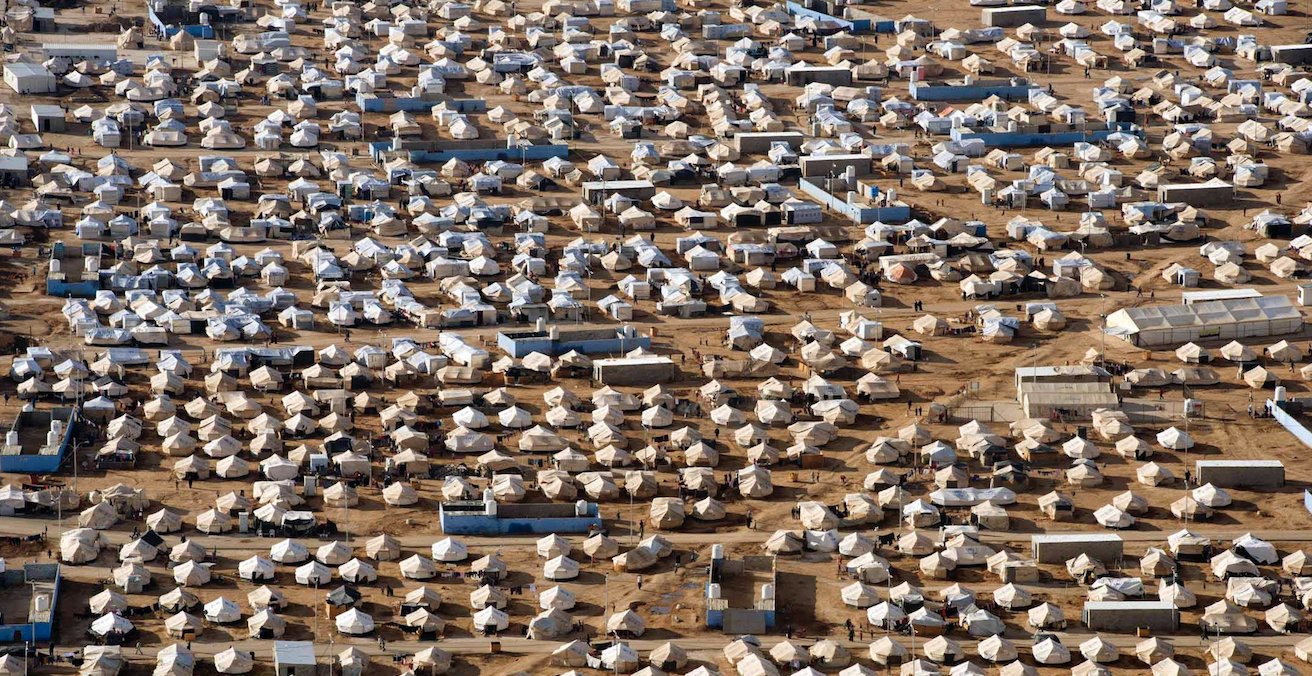

Early last week, several news agencies reported that the first cases against Syria had been filed with the International Criminal Court (ICC). For those seeking justice for the nearly 10 million displaced and over 500,000 civilian casualties, there was welcome relief in the hope that those most responsible for the heinous and barbaric crimes committed against civilians during this conflict might finally be brought to account. However, there remains a number of significant hurdles to overcome. These impediments serve to highlight the ongoing limitations of a permanent court that is designed to prosecute the “worst of the worst” but which operates in a society of increasingly self-interested states.

Syria is the ICC’s bête noire. The conflict, characterised by numerous and egregious violations of the laws of war and crimes against humanity, is exactly the type of conflict that the architects of the ICC envisioned it as a response to. It was to act as a court of last resort, where heads of state and high-ranking government and military figures, whom domestic courts either could not or would not prosecute, could be held to account for their crimes. In doing so, it was intended to overcome claims of “sovereign immunity.”

But the ICC has limited jurisdiction in Syria as it is not a party to the Rome Statute (the ICC’s governing treaty). The only other means by which the ICC could investigate alleged crimes committed in Syria is via a United Nations Security Council referral. However, as is well documented, Russia, a strong ally of the Assad regime, has vetoed or threatened to veto all efforts by the Security Council to refer the situation in Syria to the ICC.

Thus, there is great interest in the method being used in the attempt to prosecute Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, and others, for alleged crimes committed in Syria. Relying on the precedent established in 2018, when the ICC Pre-Trial Chamber ruled “that the Court has jurisdiction over the alleged deportation of members of the Rohingya people from Myanmar to Bangladesh,” the human rights groups who filed the cases are looking to the ICC to make a similar ruling regarding refugees who have fled the conflict to neighbouring Jordan.

On the face of it, the precedent is compelling. Syria, like Myanmar, is not a party to the Rome Statute, and similarly, Jordan, like Bangladesh, is a party to the Rome Statute. Furthermore, the experiences of those fleeing the respective conflicts have been well documented. But the seemingly compelling precedent is persuasive for a further, arguably more important, reason.

The heady optimism created by the signing of the Rome Statute in 1998, and the ICC coming into effect in 2002, has been juxtaposed against a weary resignation – created by the inability to prosecute those responsible for genocide and crimes against humanity in Myanmar and war crimes and crimes against humanity in Syria – that we had returned to the dark, pre-Cold War days of impunity and immunity informed by conceptions of raison d’état. Therefore, the ruling by the Court’s Pre-Trial Chamber served to re-enthuse those who had lost faith in the post-Cold War shift towards justice beyond the nation-state that was created first by the two UN-backed ad-hoc tribunals, then later by the ICC itself.

Yet there are at least two identifiable problems with the Myanmar precedent. The first is that with regards to Syria, it might not be a precedent at all. The Bangladesh/Myanmar preliminary investigation is concerned with crimes under article 7 of the Rome Statute, and, in particular, “deportation or forcible transfer of population.” Whereas there is clear evidence of a Myanmar, military-backed policy of deporting Rohingya people from Myanmar to Bangladesh, there is no evidence of such a policy as it concerns deportation or forcible transfer from Syria to Jordan. According to Josie Ensor, writing in The Telegraph, the 28 refugees on whose behalf the case has been filed, have testified “about being bombed, shot at, detained, tortured, and having witnessed mass killings since the war began in 2011, which forced them to flee.” While the gravity of the alleged crimes committed should not be diminished, the degree to which this constitutes deportation or forcible transfer, even if it was through “other coercive acts from the area in which they are lawfully present” (as outlined in the Rome Statute), will still be much more difficult to prove than in the Myanmar/Bangladesh case.

The second problem concerns the degree to which the examples of Syria and Myanmar/Bangladesh provide evidence of an ICC that has been reduced to seeking justice where it can, rather than where it should. While the ICC’s decision to pursue the Myanmar regime for “crimes against humanity” is to be applauded, there remains a sense that it would have been better had the Court been able to open an investigation into accusations of genocide.

Similarly, the crimes that have been committed during the conflict in Syria are well documented and fall under the jurisdiction of the ICC. Thus, in not pursuing the Assad regime for what one might consider the graver Article 8 crimes, such as “intentionally directing attacks against the civilian population” and the regime’s flagrant use of chemical weapons, we are left with the impression that the Court can no longer prosecute “the worst of the worst.”

It’s not all bad news, however, for those seeking justice in Syria. Courts in France, Germany and Sweden are currently investigating several Syrian individuals, including regime intelligence officers, suspected of serious crimes. Similarly, the very existence of the ICC, and other new supranational mechanisms to prosecute violations of the laws of war, genocide and crimes against humanity, has no doubt encouraged the unprecedented collation of evidence of the nature and magnitude of atrocities committed in Syria, in the hope that one day those responsible will be held to account for their crimes.

After years of frustration, the news that there are avenues for the ICC to prosecute those responsible for the crimes committed is Syria and Myanmar is be welcomed. But this remains limited justice and, as such, this might be as good a time as any to reassess the idea of the ICC as a panacea of international criminal justice.

Dr Matt Killingsworth is a senior lecturer in International Relations at the University of Tasmania. He is co-editor of Violence and the State (Manchester University Press, 2015) and the forthcoming Civility, Barbarism and the Evolution of International Humanitarian Law: Who Do the Laws of War Protect? (Cambridge University Press). His current research focuses on the evolution of the modern laws of war and the International Criminal Court. He is the chair of the Tasmanian Red Cross International Humanitarian Law Committee and a regular contributor to local and national media. He tweets at: @mevanworth

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.