Justice for the Rohingya: Regional Responsibility

Myanmar’s treatment of the Rohingya has passed the threshold for action under the Responsibility to Protect doctrine. As a regional leader, Australia has a duty to act.

This article is the second of a two-part series examining the prospect of justice for the Rohingya and encouraging anti-impunity measures in Myanmar. The first part is available here.

In 2005, the UN General Assembly adopted the World Summit Outcome Document, which included three paragraphs on the Responsibility to Protect (R2P). Since then, the principle has been referred to in multiple general assembly informal sessions, security council sessions and resolutions, and the UN secretary-general has issued a report on the principle every year since 2009.

The principle stated in the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document is the following:

- Each individual State has the responsibility to protect its populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. This responsibility entails the prevention of such crimes, including their incitement, through appropriate and necessary means. We accept that responsibility and will act in accordance with it. The international community should, as appropriate, encourage and help States to exercise this responsibility and support the United Nations in establishing an early warning capability.

- The international community, through the United Nations, also has the responsibility to use appropriate diplomatic, humanitarian and other peaceful means, in accordance with Chapters VI and VIII of the Charter, to help protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. In this context, we are prepared to take collective action, in a timely and decisive manner, through the Security Council, in accordance with the Charter, including Chapter VII, on a case-by-case basis and in cooperation with relevant regional organisations as appropriate, should peaceful means be inadequate and national authorities manifestly fail to protect their populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. We stress the need for the General Assembly to continue consideration of the responsibility to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity and its implications, bearing in mind the principles of the Charter and international law. We also intend to commit ourselves, as necessary and appropriate, to helping States build capacity to protect their populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity and to assisting those which are under stress before crises and conflicts break out.

- We fully support the mission of the Special Adviser of the Secretary-General on the Prevention of Genocide.

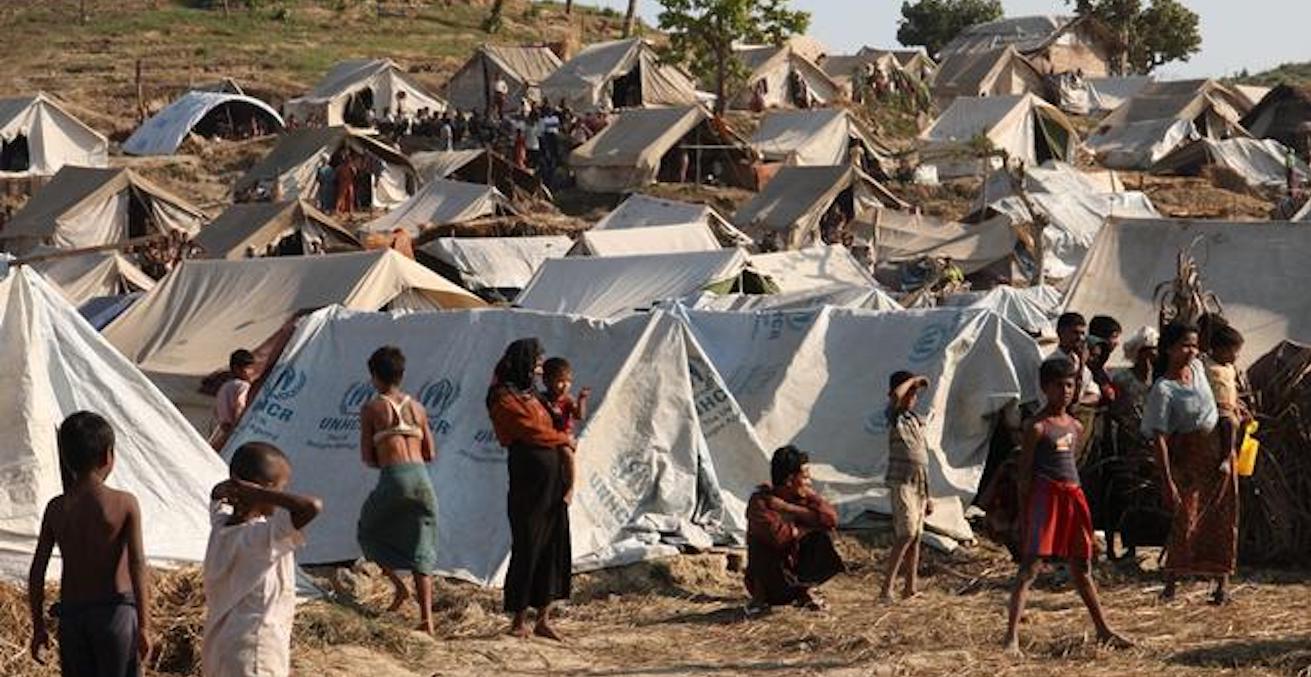

The situation in Myanmar—the constitution, the nationwide ceasefire agreement (NCA) and the political precariousness of the state counsellor role—has meant that the state is unable, probably unwilling, to protect the Rohingya population, to safely return the 700,000 living in asylum on Cox’s peninsular in Bangladesh, or to investigate the crimes committed during mid to late 2017. As such, paragraph 138 of the Outcome Document, does apply here: “The international community should, as appropriate, encourage and help States to exercise this responsibility”.

There have been three situations where the region has failed to exercise its responsibility; and there are three situations where Australia—a friend of R2P—could exercise its responsibility in the future.

First, during the UN General Assembly vote condemning the situation of human rights in Myanmar in November 2017, it was wrong of Cambodia, China, Fiji, India, Japan, Nepal, the Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Timor-Leste and Vietnam to abstain or vote against the resolution.

Second, a month later in December 2017, the UN Human Rights Council convened a special session on Myanmar. Here again, regional countries with membership on the UNHRC derogated from their obligation by abstaining (India and Japan) and voting against (Philippines and China). A UN Human Rights Council vote on the human rights situation in Myanmar was held again in March 2018 and (again) China and the Philippines voted against; Japan, Mongolia and Nepal abstained. Australia, Pakistan, and Republic of Korea voted yes. A draft resolution is once again before the council.

At the UN General Assembly vote it was disappointing to see that countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia were in the minority. A number of the countries that abstained or voted against are post-conflict countries themselves. Others are powerful states within the region: key donors and/or members on the Security Council. Collectively, their responsibility is to uphold the UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights enshrined in that charter, and to seek the protection of civilians in the region who are under threat of attack. A peaceful and secure region will not be achieved while populations are being cleansed and forcibly relocated into neighbouring territories and waters. These governments may have done a ‘favour’ for Myanmar but they have not done a favour to their regional security or their responsibility as sovereign nations.

The third occasion where it was disappointing to see little said on the situation in Rakhine State was at the ASEAN-Australia Summit in Sydney. The Malaysian president, facing accusations of corruption within his country, was the one voice that spoke out against the silence on the Rohingya situation. While we maintain that the quarrel is not with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, it was an opportunity missed to suggest a regional approach to the situation and an exploration of what ASEAN can do to support human rights in its member states. At the very least, there should have been an attempt to use this forum to push for Myanmar to agree to let the Special Rapporteur, Yanghee Lee, visit Myanmar, and to assess durable solutions for displaced persons with UNHCR.

We suggest three steps the Australian government—which has a seat on the UN Human Rights Council and is an advocate for the ASEAN regional organisation—could promote in the immediate future to address the authority, power and impunity problem in Myanmar.

First, seek to build constructive relations with the Myanmar government, specifically the state counsellor’s office with responsibility for the NCA. Discussions should focus on regional assistance and peer-to-peer exchange on supporting the NCA ceasefire monitoring committees at the state level, as well as directing funds towards legal reform and reform of the security sector within country.

Second, the avoidance of the word ‘Rohingya’ has not resolved the problem. In fact, it went a long way towards permitting the military to believe that they would get away with the cleansing operations that commenced in mid-2017. It is time to talk about citizenship, hate speech and minority communities as part of the transitional justice project in Myanmar. The NCA states that ethnic groups are equal under the constitution and that displaced communities should return to their homes. There should be priority for public information campaigns that raise awareness of hate speech, the peace process and human rights. Instead, the civil society space is shrinking, with crackdowns on journalists and repressive new protest laws.

Finally, resistance to these programs should be coupled with the public-private partnerships that are occurring in Myanmar at the same time. The peace support fund, with the assistance of the US, UK, Nordic, Canadian, German and Australian consulates, should support corporate sector engagement with justice, legal and public information campaigns. For too long the corporate sector has been permitted to get on with business while the hard work of peace to support that business is left to the government and the aid sector. Mining companies, textile and manufacturing, engineering and logging industries want to be in Myanmar, and Myanmar wants their presence; it makes sense to ensure that companies are meeting their corporate social responsibility in the locations where they seek to invest and build local business.

The world has struggled with questions of due authority, power and impunity in Myanmar for long enough. It is time to take responsibility for failing to protect the Rohingya from displacement and mass atrocities.

Associate Professor Susan Harris Rimmer is an Australian Research Council future fellow in Griffith Law School, and an adjunct reader in the Asia-Pacific College of Diplomacy at the Australian National University.

Associate Professor Sara Davies is an Australian Research Council Future Fellow and Associate Professor, Centre for Governance and Public Policy, School of Government and International Relations, Griffith University. She is also an Adjunct Associate Professor, School of Social Sciences, Monash University.

This article is part of a two-part series examining the Justice for the Rohingya and encouraging Anti-Impunity Measures in Myanmar. The first part is available here.

This article is published under a Creative Commons licence and may be republished with attribution.