ISDS Arbitration Upholds Australia’s Plain Packaging Laws

Tobacco giant Philip Morris has lost a major international legal battle to reverse Australia’s plain packaging laws by using the Australia–Hong Kong Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement (IPPA) of 1993. On 17 December 2015, a three-member arbitral tribunal at the Permanent Court of Arbitration ruled that Philip Morris had no jurisdiction to bring the case against Australia. This means that Australia’s plain packaging laws, which ban all branding from cigarette packets, will remain in force.

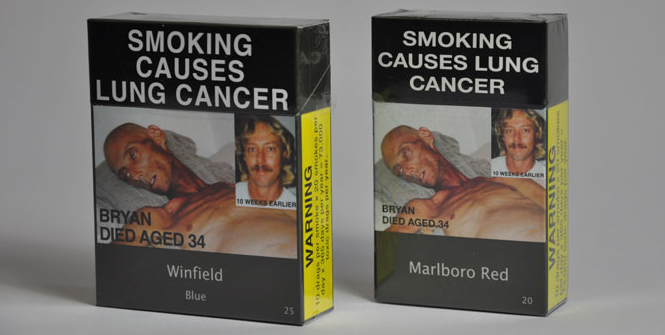

In 2011, Australia enacted the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act and enforced regulations that prohibit the display of brand trademarks, logos and designs on cigarette packets. Under these rules cigarette packets should follow standardised branding and include graphic health warnings.

Australia’s IPPA with Hong Kong provides for an investor–state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanism under which foreign investors can sue host states directly and seek monetary compensation if their profits have been hurt by the introduction of undue regulatory measures. After having lost a case in the Australian courts, Philip Morris Asia Limited (Hong Kong) initiated an ISDS claim in 2011. The arbitration hearings began in early 2015 in Singapore.

Philip Morris challenged Australia’s plain packaging laws on the grounds that the ban on trademarks breached the investment protection obligations listed under the Australia–Hong Kong IPPA. Relying primarily on the fair and equitable treatment provision, the company argued that the plain packaging laws constitute an expropriation of its intellectual property rights. The company demanded that Australia suspend the enforcement of these laws and compensate it for any losses.

For its part, the Australian government claimed that plain packaging rules were implemented for the legitimate public purpose of protecting public health. The government maintained that plain packaging measures would help in reducing the appeal of tobacco products, while mandated graphic health warnings would educate consumers about the harmful effects of smoking. According to official estimates, smoking alone kills 15,000 Australians each year and costs AU$31 billion (about US$22 billion) in social and economic costs.

The Australian government sought to dismiss the case on procedural grounds. In particular, the government raised objections to the manner in which Philip Morris restructured itself when its Australian subsidiary (Philip Morris Australia) became wholly-owned by Philip Morris Asia Limited (Hong Kong) in February 2011.

Australian authorities argued that the rearranging of company’s assets was conducted so that the dispute would be covered by the Australia–Hong Kong IPPA. They claimed that the dispute was the sole intention of the acquisition and that the company made false statements before the concerned authorities at the time of acquiring the Australian subsidiary. The government contended that the commencement of the arbitration by Philip Morris shortly after the restructuring of assets should be considered an abuse of rights and the company was therefore not entitled to an ISDS claim under the IPPA.

The unanimous decision to uphold the tobacco control measures has been welcomed by public health experts and civil society groups throughout the world. While Philip Morris may appeal the decision, it would be a herculean task to prove that such measures do not yield positive health outcomes. Australian authorities stress that the full effects of anti-tobacco measures will be seen in the long term, but statistics already show that the total consumption of tobacco and cigarettes has declined in the country since the measures were introduced in 2012.

While Australia is the first country in the world to implement tobacco plain packaging laws, the verdict against Philip Morris may encourage many other countries to implement anti-tobacco measures within their jurisdictions. New Zealand is expected to pass the Smoke-free Environments (Tobacco Plain Packaging) Amendment Bill in early 2016. And France, Ireland and the UK have also announced their plans to introduce similar measures. The inclusion of the tobacco ‘carve-out’ in the negotiated text of the investment chapter of the Trans-Pacific Partnership is viewed by many as another major victory for public health.

Still, the grim fact remains that Australia is a signatory party to more than two dozen agreements with ISDS obligations that grant foreign investors the right to challenge tobacco plain packaging and other initiatives to protect public health.

Australia is already facing another legal battle against plain packaging rules at the WTO. In 2012, Indonesia, along with Ukraine, Honduras, the Dominican Republic and Cuba challenged Australia’s plain packaging regime on grounds that they are inconsistent with the country’s obligations under the WTO’s Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights agreement. In June 2015, Ukraine decided to drop its legal proceedings against Australia but the other four tobacco producing countries are still pursuing the case. A decision is expected sometime in 2016.

Yet, the Philip Morris case highlights that investor–state arbitration has substantial financial implications even if the host state wins the case. Unofficial estimates suggest that the Australian government might have spent anywhere between AU$30 and AU$50 million (about US$21–32 million) in defending the case. The high costs of ISDS agreements point to the need for India, Indonesia and other countries that are currently revisiting their investment treaty regime to seriously rethink the inclusion of ISDS mechanisms in future investment treaties and trade agreements.

Kavaljit Singh works with Madhyam, a policy research institute based in New Delhi. This article originally appeared on East Asia Forum on 15 January. It is republished with permission.