Is Saudi Arabia's 2030 Vision Short-Sighted?

With the drying up of oil revenues and lower oil prices, Saudi Arabia now has a vision document in place to deal with its social and economic crises. But given a weak public administration and lack of demand for private jobs, the state will have a tough time altering the social contract with its people.

The fall in oil price from its mid-2014 peak of US$100 per barrel to around US$45 today has forced Saudi Arabia, which produces around 13 per cent of the world’s oil, to rethink its social and economic policies. The ruling family has a dilemma: without limitless wealth to hand out, how can it keep its citizens content? Published on 25 April, Vision 2030 provides a statement of aspirations which describe a series of major reforms. Fronted by King Salman’s son, Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the document advocates structural changes to the state and growing the private sector.

Over 70 per cent of the Saudi government’s income consists of oil revenues. This money is distributed to its people through a mixture of subsidies and public sector jobs. Petrol costs US$0.24 a litre. The King Abdullah Scholarships Scheme has sent over 180,000 Saudi students to international universities, costing US$6 billion. The ruler’s largesse is not solely altruistic; it forms a social contract between him and his citizens that replaces democratic participation.

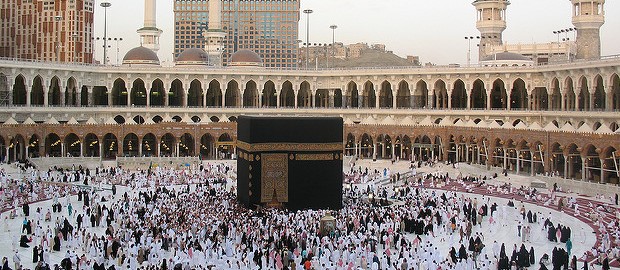

In addition to financial generosity, the King’s legitimacy is derived from his position as a custodian of Mecca and Medina, two of Islam’s holiest sites. The kingdom also encourages social conservatism by imposing a strict form of Sharia, which prohibits women from driving and results in arcane punishments. A favourite Saudi apocryphal anecdote involves a man congratulated by friends for overturning a theft charge. He has stitches around his wrist where his hand has been sewn back on. Nevertheless, shifting demographics suggest possible change; 47 per cent of Saudi’s 31 million people are less than 25 years old.

With the low oil price, the state can no longer keep its end of the bargain. Vision 2030 lays out the objectives of the transformation. The primary aim is to reduce the economy’s reliance on oil revenue. This will be achieved by floating 5 per cent of ARAMCO (the state-owned oil company estimated to be worth US$2 trillion) and placing it into the Public Investment Fund, which will invest in private enterprise. The document provides initiatives for the private sector. For example, Saudi’s enormous defence budget will be used to develop an indigenous defence manufacturing capability within 14 years and require foreign arms sellers to build in the kingdom. Public subsidies of fuel will be cut. Desert nights will get colder and heating bills will rise by over 50 per cent. Earlier this month, the document provided the catalyst for what is regarded as Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s cabinet reshuffle, which gave more power to technocrats and the younger generation. The elderly oil minister was replaced and a new competition authority was established to challenge entrenched interests.

The kingdom must uphold or alter the social contract. However, Vision 2030’s goals will be difficult to implement given the lack of depth and skills in the public administration. Furthermore, the labour market will have to be reformed. It will be hard to persuade Saudi citizens who expect state jobs to take low-paid, demanding jobs in the private sector.

Currently, the economy depends on foreigners who make up 30 per cent of the population for menial labour and management expertise. Added to Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s uneasy relationship with the conservative clerics and the ongoing tension with Iran, the task is enormous. In any event, the document’s time frame is highly ambitious and relies upon 80-year-old King Salman surviving. If he dies, Mohammed bin Nayef, the current crown prince and a highly effective interior minister, will become king and Saudi may go in a different direction. The question is whether there is enough time to transform Vision 2030 from imagination to reality and keep the 47 per cent happy.

Dominic Williams is an economic and political analyst at Dragoman Ltd. Follow him and his employer on Twitter @domwilliamsinic and @DragomanPtyLtd. This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.