Is Democracy in Retreat?

As part of the Millenium Project, 15 Global Challenges have been established to provide a framework to assess the global and local prospects for humanity.

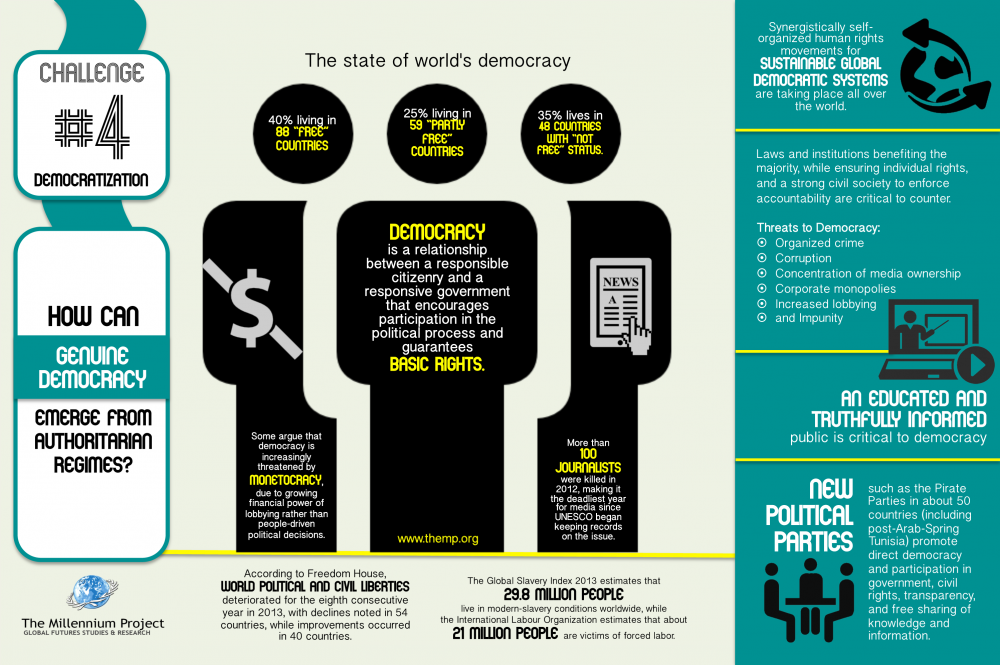

One of these urgent challenges is the retreat of democracy around the world as more nations roll back the hard fought democratic freedoms.

After peaking in the late 1990s, democracy around the world appears today to be in retreat, with a resurgence of authoritarian regimes such as Russia and the failure of weak quasi-democracies across the world.

Freedom House, the US think tank, produces an annual report on political rights and civil liberties in 195 countries around the globe. Their latest report, Freedom in the World 2015 – ominously sub-titled ‘Discarding Democracy: the Return to the Iron Fist’ – cites more aggressive tactics by authoritarian regimes and an upsurge in terrorism as key factors.

They found a decline in the extent of democracy globally over 2014 – a process of democratic drawback that is now in its ninth consecutive year. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a rollback of democratic gains in Egypt, Turkey’s intensified campaign against press freedom and civil society, and further centralization of authority in China were all cited as evidence of a growing decline of democratic liberties.

According to Freedom House, less than half the world’s states – and much less than half the world’s citizens – are now located in democracies, a sharp decline on a decade ago. Of the 195 countries assessed, 89 (46 percent) were rated Free, 55 (28 percent) Partly Free, and 51 (26 percent) Not Free.

These trends suggest that “acceptance of democracy as the world’s dominant form of government—and of an international system built on democratic ideals—is under greater threat than at any point in the last 25 years … developments in 2014 were exceptionally grim. The report’s findings show that nearly twice as many countries suffered declines as registered gains, 61 to 33, with the number of gains hitting its lowest point since the nine-year erosion began”.

There is, however, some brighter news closer to home. The Asia-Pacific was the only world region that registered as many gains as declines in civil rights and political freedoms. Even there, however, gains in East Timor and the South Pacific were offset by ongoing uncertainties in the political evolution of transitional states such as Myanmar and Thailand. Indonesia, possibly the most important test case for democracy worldwide given its size and religious composition, was relegated to ‘party free’ status by Freedom House in 2014 as a result of its declining civil liberties.

We are thus left with something of a paradox. Today, more Asians live in electoral democracies than ever before, and Asian regimes are increasingly using their democratic status to lift their prominence in the international arena. New or restored democracies ranging from Mongolia in the north to East Timor in the south have joined Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines and Indonesia as classic ‘third wave’ democracies in which governments are chosen and changed via the electoral process. In short, gains in the formal institutions of democracy such as elections and political parties have been widespread.

At the same time, however, as the scope of democracy across Asia has spread, its quality has arguably declined. Some former democracies, such as Thailand, have experienced repeated and debilitating democratic failures, while others, including the crucial case of Indonesia, have seen an apparent erosion of democratic capacity and commitment even as their formal processes such as elections improve. Ineffective governance, rising intolerance of religious minorities and the ever-present scourge of corruption all undermine the promise of democracy, particularly in comparison to the ‘Beijing model’ of centralised state-led development.

The geopolitics of democracy is also becoming more important in Asia. The rapid integration of mainland SE Asia into a China-centred regional economy is inevitably having political as well as economic impacts, making it increasingly difficult for countries seeking to (re)transition to democracy, such as Thailand and Myanmar, to exercise their full sovereignty within the context of a regional “great game” for supremacy in Asia.

Conversely, resolutely authoritarian states like Vietnam are under pressure to loosen their political model and address human rights issues in part because of their growing rapprochement with the United States – itself driven, of course, by concerns about China. Similarly, North Korea’s totalitarian regime continues to be propped up by China — in part because of China’s aversion to the idea of a united (and pro-US) Korea on its doorstep. More than ever, it is hard to disentangle democracy’s domestic context from its international one.

Professor Benjamin Reilly is Dean of the Sir Walter Murdoch School of Public Policy and International Affairs at Murdoch University. This article can be republished with attribution under a Creative Commons Licence.