International Security and Antimicrobial Resistance: Why Policy Coherence Matters

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a health security issue presenting unique challenges not only to human and animal health but also to economic and trade agendas.

Current tactics to combat AMR focus on preserving the effectiveness of antibiotics and on developing these unique health tools. While increased public funding has produced some progress (along with the recent announcement that scientists have discovered what could be the first new antibiotic in 25 years) scientists caution that the availability of new antibiotics is still some years away.

Public health experts generally accept the World Health Organisation’s Global Action Plan concerning AMR. However, much of their framework remains to be given concrete form, including the basic usage and surveillance data necessary for any evidence-based policy approach.

Comprehensive data about the translational effects of antibiotics across various sectors of the economy is necessary to develop coherent strategies to combat AMR. Of particular concern is that we don’t yet understand how using antibiotics in industrial food production may undermine their effectiveness, nor do we understand the health consequences of new bugs that may evolve in this environment. An alternative policy could be adopting a more proactive and precautionary approach, implementing more stringent standards for food production. However, industry pressure would likely inhibit governments from taking such measures.

Concerns about AMR transcend national boundaries. Nevertheless, political leaders have been slow to recognise how the public, health systems and the economy are impacted by AMR. A recent report undertaken in the UK provides rather scary food for thought, asserting that drug-resistant superbugs could cost the global economy as much as $100 trillion between now and 2050.

Reasons for this slow response can be traced back to the diversion of resources and health policy leadership after 9/11. WHO issued its first major report on AMR – Global Strategy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance – on the eve of 9/11, meaning little if any notice was taken of its attempt to issue a health security wake up call. A decade and a half on, governments are beginning to take notice. However, much more attention is needed to combat the challenges of AMR.

Market Failures

Despite the recent announcement that scientists have discovered a new antibiotic teixobactin, no new class of antibiotic has entered the market since the mid-1980s. This is a significant and disturbing market failure notwithstanding the legal and monopoly privileges provided to patents as well as the substantial political support offered to the pharmaceutical industry.

While slightly chastened and aware of the public relations consequences, pharmaceutical companies may still be tempted to manipulate this health security issue to argue for further monopoly protection. However, the EU and US are already providing significant incentives to counteract this problem. The US has provided greater patent support against generics entering the market introducing the GAIN Act and, along with the EU, provides major funding support to develop new drugs alongside specific innovation rewards. On the regulatory front, the EU and US are working to minimise the time and administrative burdens for obtaining regulatory approvals.

A Clash between Health Policy and Trade Obligations

There are a number of economic and legal obligations that need to be included in the policy framework addressing AMR. Existing WTO obligations should be sensitised and in some cases neutralised proactively to prevent AMR policies from clashing with trade obligations. The quantitative data pertaining to industrial food production is startling, indicating that between 70 and 80 per cent of antibiotics are used in various forms of food production. National measures to block importing antibiotic resistant strains via food production should not become hostage to threats of a WTO dispute resolution, despite the incumbent political baggage that this may involve.

Here, WHO/FAO Codex Alientarius is an important institution, setting international food safety standards used by the WTO. Given the heath security problems associated with AMR, the Codex system needs to be made more sensitive. Effective global databases to collect and quickly disseminate information about AMR are also essential.

Further, cheap, accurate and rapid diagnostic tests to identify bacterial infections (essential to conserving antibiotics) have not been developed. However, recent changes to US intellectual property policy may promote development of diagnostics by placing limits on patents concerning gene sequences. Other countries should follow the US’ lead, since the EU, Japan and Australia continue to allow patents over naturally occurring gene sequences.

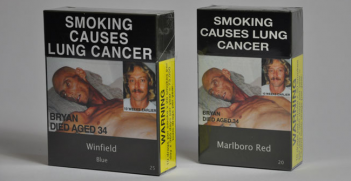

Alarmingly, investment agreements promoted in bilateral and regional FTAs can be used to sue governments for implementing policies or regulatory changes to counter AMR. For example, corporations can challenge domestic or import production standards for food production processes or labelling requirements, many of which may compromise AMR strategies. Phillip Morris’ case against the Australian Government’s plain packaging policy for tobacco illustrates corporations’ willingness to initiate these challenges.

However, agreements such as the Australia-US FTA and the Trans-Pacific Partnership are also used to promote and harmonise regulatory measures, standards and labelling requirements across borders. These legal obligations enable corporations to lobby at governmental levels about health or transparency measures. For example, the US introduced domestic changes to the use of antibiotics in animals. However, this was limited to ‘voluntary’ implementation.

The global health industry is also influenced by trade imperatives, promoting the comparative advantage of developing countries’ ‘health tourism’ initiatives. Western governments seeking to minimise their domestic health budgets may be tempted to actively promote such policies. Unfortunately, this may lead to greater AMR transmission globally, increasing domestic health costs. Governments and/or health insurers tempted to minimise costs by promoting these models should consider the price of dealing with increased cross-border transmissions of superbugs.

Overall, the most effective means we have to address AMR is implementing better basic public health strategies. These strategies are neither novel nor rocket science. Nevertheless, millions of citizens do not have access to hygiene, sewerage, toilets or clean water. The rise of AMR is yet another reason to prioritise these essential life-enhancing services.

Anna George is Adjunct Professor, Sir Walter Murdoch School of Public Policy and International Affairs, Murdoch University and Associate Fellow, Centre on Global Health Security, Chatham House. This article can be republished with attribution under a Creative Commons Licence.