Inequality and Indifference: The 2020 US Presidential Race

In the Democratic Party’s presidential primaries, the candidates face a paradox: the country is confronting worsening inequality, yet there is consistent indifference to the issue within key constituencies.

In the midst of a divisive impeachment trial of the 45th president of the United States, ongoing tensions in the Middle East, and a global health emergency, eight candidates have been campaigning to secure the nomination of Democratic presidential candidate. While ongoing problems are a constant source of media attention, the Democratic presidential hopefuls have been consistently emphasising another issue: inequality. Why have the Democratic primary candidates given such priority to the issue of inequality, and how are they talking about it?

The most unequal industrialised country

At first glance, the answer to why the Democratic candidates are emphasising inequality seems obvious: the US is the most unequal liberal democracy in the industrialised world. The wealthiest ten percent of households control approximately 79 percent of wealth. Large corporations avoid federal taxes, and the country has one of the lowest minimum wages at US$7.00 per hour. The country lacks universal public healthcare, access to higher education is strongly determined by family wealth, and homelessness has grown rapidly in key cities. Racial and ethnic divides compound economic inequalities, producing residential segregation, disproportionate incarceration rates, and higher poverty rates for Latinos, African Americans, and Native Americans.

However, the American public does not appear to be especially concerned about inequality. This is partly because inequality is a complex, multidimensional concept. Inequality is shaped by many elements, including wages, wealth, tax and benefit systems, and access to public and private services. Because of its complexity, discussions about inequality often reduce the issue to statistical measures, oversimplifying the phenomenon and turning it into an abstract, impersonal issue.

Another reason may be cultural. In the US, there is a pervasive assumption that wealth and poverty result from personal effort rather than structural forces beyond an individual’s control. A recent survey found a majority of the population – even in the poorest segments of society – believes that through hard work, everybody can succeed in the “land of opportunity,” that they will be better off than their parents, and their children will be better off than them. Furthermore, only 37% of low-income (below $35,000) Americans believe that economic success is the result of being raised in a well-off family. 87% of the same cohort think hard work is the cause of personal prosperity.

Given the indifference in the public’s attitudes towards inequality, the degree of attention paid to the issue by democratic candidates is surprising. Still, worsening inequality negatively affects the Democratic Party’s core constituency and so the candidates face pressure to address the issue.

Framing income and wealth inequality

To address inequality in political debates and public policy, it must be framed as a problem needing public intervention and capable of rectification. Framing involves three interconnected elements: selecting, naming, and storytelling. Selecting involves highlighting particular features of an issue while leaving aside others. Naming is the political act of applying labels to policy problems to invoke particular values, shape public interpretations, and evoke reactions to an issue. Storytelling ties the elements of a policy frame into a coherent narrative that simplifies the problem for easier public transmission and reception. Stories often identify and separate out the ‘good guys’ from the ‘bad guys’ in a policy issue, and always tell us how the proposed policy solution will solve the identified problem.

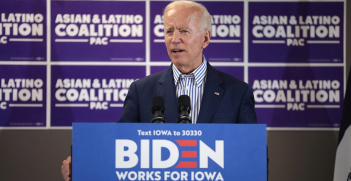

The Democratic primary candidates have deployed different frames to talk about income and wealth inequality. Joe Biden’s plan – “Joe’s Vision for America” – frames inequality by selectively focusing on the middle class, which he names “the backbone of the country.” Relying heavily on the idea of the “American Dream,” Biden avoids direct references to inequality, keeping the issue abstract. However, he offers hints about it, and even acknowledges intersections of inequality. His storytelling suggests that investing in infrastructure and transportation will lead to job creation. Taxing the super-wealthy and corporations, closing tax loopholes, and strengthening workers through unionisation and collective bargaining, will rebuild the middle class. Biden avoids explicitly identifying “bad guys,” though he clearly sees the middle class as the “good guys” of society and an expanded middle-class as the major driver of fairness and opportunity.

In contrast, Sanders’ rhetoric confronts income and wealth inequalities directly. His framing focuses on tax and names problems of “extreme wealth,” which is expropriated by “the rich” and “large corporations” at the expense of a “disappearing middle-class.” Sanders suggests taxing extreme wealth to finance housing, universal childcare, and healthcare for all. His “income inequality tax” plan aims to pay workers “adequate wages” by taxing corporations in which there are excessive gaps between CEO and median worker pay. Revenues will be used to eliminate medical debts. Finally, through “tax increases for the rich,” he suggests progressive estate taxes on multi-millionaire and billionaire inheritances and a Wall Street speculators tax. Sanders explicitly names the irresponsible speculators, domineering corporations, and the selfish super-wealthy as the “bad guys.”

Elizabeth Warren’s platform is also explicit about the issue of inequality. Warren focuses on the wealthiest households, claiming that her “ultra-millionaire tax” – two percent on incomes over $50 million – will help to rebuild the middle-class. Warren plans to address income inequality through combating wrongful practices created by giant corporations and “their allies in Washington and in state governments.” She plans to extend rights, strengthen workers’ protections, and raise wages and minimum safety nets. Similar to Sanders, Warren names the bad guys and tells a story about saving the disadvantaged and the middle-class from powerful economic and political interests.

Finally, Pete Buttigieg follows Biden in generally avoiding direct references to inequality. Nevertheless, Buttigieg acknowledges that inequality harms not only the economic security of working and middle classes, but also democracy. In contrast to his colleagues, he avoids talking about taxation. Buttigieg promises to lower costs on key goods and services – housing, childcare, education, healthcare, and prescription drugs. He wants to raise incomes, especially where gender, race, and ethnicity have led to pay gaps. Finally, he aims to create jobs and strengthen workers’ rights and protection. Buttigieg does not directly identify the “bad guys,” but provides a broad coalition of “good guys” who he claims will benefit from his multifaceted plan for economic renewal.

Implications for the politics of inequality

Wealth and income inequality are not new phenomena in the USA, but they are reaching levels that concern scholars and policy makers. Inequality impacts the daily lives of millions of people, as well as the accessibility and effectiveness of democratic processes and institutions. Wealth, like poverty, is intergenerational. If existing concentrations of wealth, where the bottom 60% of the population only holds 2% of total net wealth, are not addressed, then the “American Dream” will cease to have meaning for much of the population.

Democratic primary candidates emphasise the issue of worsening inequality because it directly affects their core constituency, offends their values, and presents a serious policy problem for the country. Yet each candidate has taken a different route to navigate this complex and controversial issue that struggles for broader political attention.

The unfolding primary elections will show which frames will gather more support. In the process, candidates are triggering dynamic policy debates. While these efforts to highlight and frame the issue of inequality may not result in policy change in the short term, they could change the attitudes and beliefs of voters about the impact of inequality on individuals’ life chances.

Diana Leon-Espinoza is a PhD candidate at Griffith University researching gender politics and work-family policies in Latin America. Dr Cosmo Howard is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Government and International Relations at Griffith University.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.