The Indonesian Oligarchy’s Islamic Turn?

Former Jakarta Governor, Ahok, withdrew his appeal against blasphemy charges this week and will spend two years in prison. Rather than a broad turn toward Islamism, however, the case shows Indonesian oligarchs’ willingness to exploit social divisions to advance their own interests.

Unlike the close election predicted by most pollsters, in the end former Minister of Education Anies Baswedan soundly defeated incumbent Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (‘Ahok’) in the hotly contested second round of the Jakarta gubernatorial election on 19 April 2017. To add to Ahok’s woes, a Jakarta court subsequently slapped him with a two-year sentence for committing ‘blasphemy’ against Islam during an off-the-cuff campaign speech and he was promptly jailed on 9 May.

The 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election was the most divisive in Indonesian history, even more so than the 2014 presidential election in which Joko (‘Jokowi’) Widodo defeated New Order-era strongman, Prabowo Subianto. The outspoken and abrasive Ahok was hampered both by his Chinese Christian ethnicity and by his urban rejuventation policies, which have evicted many urban poor in Jakarta. He made himself an easy target for mass mobilisations, which combined calls for Islamic solidarity with a longstanding narrative about the oppression and marginalisation of the ummah (community of believers). This narrative goes hand in hand with the idea that Indonesia’s ethnic Chinese minority disproportionately benefited from preferential economic treatment by the Dutch as well as the authoritarian New Order, at least until its final years.

So, has Indonesian democracy been overwhelmed by an aggressive ‘Islamism’ or even ‘Islamic radicalism’? This is a significant question given that Indonesia has been seen as a case of successful democratisation since the fall of Soeharto’s New Order in 1998. It is now considered the third largest democracy in the world. As a multi-ethnic and multi-religious country with the world’s largest concentration of Muslims, it has also been depicted as a place where a ‘moderate’ form of Islam could cohabit with social pluralism and democracy. This is despite the Bali bombings and the presence of small bands of violent Al Qaeda or ISIS-admiring terrorists. Does the spectacular fall of Ahok, who was considered almost unbeatable a year ago, mean that we must revisit our assumptions about Indonesia?

Another way to understand the events surrounding Jakarta’s gubernatorial election is to connect it to broader conflicts within Indonesia’s oligarchy. It is true that the mobilisation of Islamic identity against Ahok, spearheaded by the notorious Islamic Defenders Front (FPI), was crucial in Anies’s victory. This is so even if the FPI’s efforts initially seemed to cater toward Agus Yudhoyono, son of former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, who was eliminated decisively in the first round. But all three candidates essentially served as proxies for different coalitions of long-entrenched oligarchic elites. Ahok himself represented a coalition driven by the PDI-P (Indonesian Democratic Party for Struggle), led by another former president, Megawati Soekarnoputri, with which Jokowi is aligned. Anies, who had been sacked from the Jokowi cabinet, competed on behalf of a bloc put together by Prabowo’s Gerindra (Greater Indonesia) Party, which had the apparent backing of the ambitious ethnic Chinese tycoon Hary Tanoesoedibjo and the Soeharto family, keen on making a comeback after two decades in the political wilderness. Agus Yudhoyono’s candidacy represented an attempt by his own family, which controls yet another party, the Democrats, to establish something resembling a political dynasty.

Jakarta’s gubernatorial election was therefore a dress rehearsal for the upcoming Indonesian presidential election in 2019. It is likely that Jokowi (notwithstanding intermittent problems with the PDI-P’s matriarch) will be pitted against Prabowo again. The president remains popular, notwithstanding his failure to deliver on many of his campaign promises, dependent as he has been on oligarchic elites in control of the parties that nominally support him in parliament. Few would be surprised if Prabowo put his hat in the ring again for the next contest. Ironically, he might be somewhat wary of Anies’s own presidential ambitions. Prabowo has reason for concern: though instrumental in Jokowi’s ascension onto the national political stage, the latter ended up scuppering the former Soeharto son-in-law’s presidential bid in 2014. One way to avoid a repeat scenario might be to pick Anies as running mate.

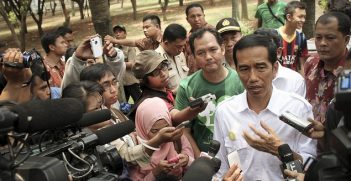

It is against this background that events rapidly followed Ahok’s defeat. Ahok was sentenced to a heavier term than the prosecution had requested, and many supporters lamented Jokowi’s perceived lack of protection for the deputy who served him when he was governor of Jakarta in 2012-2014. Leaving aside that such an intervention posed its own legal and ethical problems, they would not be wrong to think that the president is looking out for his own political future. It is likely, after all, that the same tactics of mobilising identity politics against Ahok will be used against him. There is already rumour-mongering in social media about Jokowi’s background (which, if to be believed, would mean that Indonesia’s president is a closet ethnic Chinese communist, a characterisation well-suited to building up Islamist antipathy).

But Jokowi has had to play a careful balancing act. He needed to offer something tangible to those who see him as a bulwark against Islamic radicalism. There is delicious irony in the police investigation into the leader of the FPI, Habib Rizieq Shihab, for an alleged indiscretion laughably prosecutable under a wide-ranging anti-pornography law; but clamping down on the organisation directly would be politically difficult. Not only does the FPI have backing within Indonesia’s military, it has shifted from the fringes of politics to nearer the centre due to its ubiquitous role in the anti-Ahok mobilisations. More vulnerable is the Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia, which the Indonesian government is attempting to ban, ostensibly for being against the state ideology known as Pancasila. No doubt the move is also meant to strike fear among those preparing to mobilise hard-line Islamic groups against the president.

In the meantime, the ad-hoc nature of political coalition building in Indonesia’s democracy has been openly displayed. Golkar stalwart and businessman Aburizal Bakrie was seen partaking in Anies’ victory celebration despite the party officially backing Ahok. Even Vice President Jusuf Kalla, another Golkar stalwart and businessman, quietly backed Anies, perhaps as a reaction to being sidelined. Much more credible than the likes of Prabowo, Bakrie or the Soehartos as a Muslim leader, Kalla glaringly failed to offer help to Ahok in dispelling criticism that he harboured an anti-Islamic agenda.

Ahok’s defeat in the face of FPI-led mobilisations is less a sign that Islamic radicalism has gained ascendancy in Indonesian politics than of the ability of oligarchs to use their social agents for their own interests. But by facilitating the venting of the frustrations of ordinary Indonesians through a religious-political lexicon, Indonesian oligarchs have all but ensured the further growth of illiberal forms of Islamic politics, which will challenge Indonesia’s social pluralism and tolerance. In turn, Indonesian democracy will be ever poorer in safeguarding citizens’ rights compared to safeguarding elections.

Vedi R. Hadiz is Professor of Asian Studies at the University of Melbourne.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.