India at 70: The Absurdity of Hope

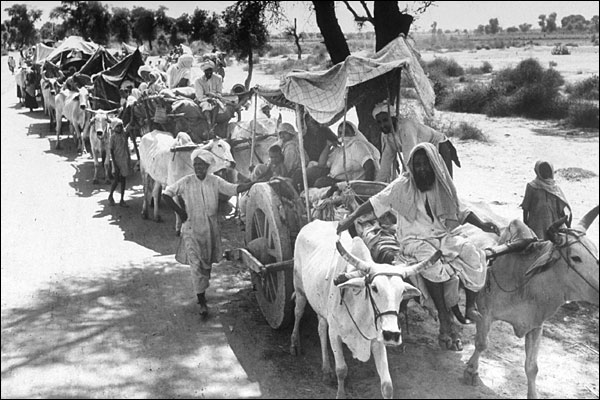

The 15th of August is celebrated by more than a billion people as Indian Independence Day, but the irrational circumstances of the Partition continue to cast a shadow 70 years later.

The most important thing to keep in mind about the Partition of the subcontinent is that it was completely absurd. The Indo-Pakistani writer (Partition divided him, like so many others) Saadat Hasan Manto expressed this absurdity in his short stories about the event. He captured the physical, emotional and psychological violence of Partition in a way that very few could or would. Manto’s story, Toba Tek Singh, is something that should be read by all scholars of South Asia.

Today in India, 70 years after Partition, much of the absurdity continues. The political wing of the organisation that inspired the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi runs the government; in the heartland of this rising global power there have been lynchings over the possession and consumption of beef; the world’s largest democracy is fiddling its history textbooks once again. What would Manto say?

Most analyses about the impact of Partition begin with Kashmir, and perhaps with good reason. But like so many stories about Partition, its history is also somewhat absurd. From the outset there was trouble in Kashmir, as there is still.

At the time of Partition it was ruled by the slightly off-balance—if highly entertaining—Maharaja Sir Hari Singh. Sir Hari was a favourite of Time Magazine, which was only too pleased to report his many and various indiscretions, particularly a rather amusing Parisian jaunt in 1919 that featured the “bewitching” Mrs Maudie Robinson and her furious husband.

At home in Kashmir, the Maharaja was in theory pro-British but in practice a thorn in the Raj’s side. Sir Hari took some delight in irritating the British as much as possible. In 1928, while the British Resident was out of Kashmir on official business, Hari had the flagpole bearing the Union Jack removed from the lawns of the British Residency and disappeared. (Needless to say the Resident was equally baffled and disgruntled.)

As British withdrawal from India gathered steam and the princely states began to choose between India and Pakistan, Sir Hari’s astrologer and clairvoyant declared that the long-deceased founder of the state, Maharaja Gulab Singh, favoured an independent Kashmir. Sir Hari seemed similarly inclined. Yet, when the time came to make a decision, the Maharaja feigned an attack of colic and went into hiding. He would (eventually) accede to India under the threat of insurrection from a Muslim resistance movement that united with tribesman from the north-west frontier territories (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa).

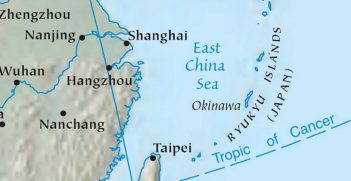

Today, the Kashmiri border between India and Pakistan is rather wistfully called the Line of Control (LOC). The LOC denotes the ceasefire line agreed upon in the 1972 Simla Agreement and it is marked, on the Indian side, by a 550km-long fence.

In 2011, Rashid Lone, a farmer in the Gurez Valley in Indian Kashmir’s Bandipora district, explained that “cattle put out to graze in the area between the fence and the LOC wander off to the Pakistani side and are lost forever.” Lone’s neighbour, Touseef Bhat, whose scenic seven-acre farm featured an incongruous electrified barbed wire fence cutting across its centre, added, “sometimes we have to walk several kilometres to a crossing point just to visit a neighbour who may only be a shouting distance away on the other side of the fence.”

While Sir Hari was stealing the British Resident’s flag and gallivanting around the French capital with Maudie Robinson, far more brilliant minds were thinking about what an independent India should look like. Amidst this milieu of Indian nationalist thought, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) developed as a reaction to the perceived threat of Muslims to Hindus.

The RSS existed then, as it does now, in the guise of a paramilitary organisation and relied on a particularly xenophobic brand of nationalism that regarded Muslims as second-class citizens and Hindus as the original, rightful people of India. The organisation found meaning and an ideological identity in the idea of Hindutva, or Hindu-ness. The RSS recruited—and still recruits—young men, and trained them for a life of service to the Hindu Rashtra (Hindu nation) and sought to create a nation state run for and by Hindus. It remains controversial; Gandhi’s assassin, Nathuram Godse, had been a member of the RSS.

The political wing of the RSS is the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), now in government under the leadership Narendra Modi. In February 2002 the western Indian state of Gujarat—then governed by Narendra Modi—witnessed large-scale rioting. Official numbers released in 2005, reported that 790 Muslims and 254 Hindus were killed, with 223 people reported missing and 2,500 injured.

Modi was denied a United States visa for his role in the riots, until his election as prime minister of India in 2014. Modi has always denied any role in the rioting but his rise to power caused much soul searching in India, and much commentary abroad. When it became clear that he was positioned to become India’s next prime minister, there was a wringing-of-hands, led mainly by left-leaning ‘intellectual’ Indians who were no longer resident in the country. Salman Rushdie, among others, wrote an open letter to The Guardian arguing: “Were [Modi] to be elected prime minister, it would bode ill for India’s future as a country that cherishes the ideals of inclusion and protection for all its peoples and communities.”

Others, myself included, were doubtful of how far down the path of radical right-wing Hindtuva Modi could travel in an India that was still democratic and (officially) secular, without seriously jeopardising his party’s re-election chances in 2019. However, with growing numbers of ‘beef lynching’ incidents there has come the realisation that even if Modi is (at least to some extent) bound by political restraint, his followers—including the RSS—are not.

As the Indian government saunters closer to Hindu majoritarianism the old ghosts of Partition—or were they never really ghosts?—rise up. The most devastating ‘ghost’ being that the Hindu-Muslim violence of Partition was inevitable and somehow is still inevitable in India. Gandhi had told Mountbatten repeatedly that there were only two options: continued British rule or a bloodbath. Mountbatten eventually turned to Gandhi and asked what he should do. Gandhi replied, “you must face the bloodbath and accept it”. Partition makes us wonder if the djinn of communalism will haunt the subcontinent forever.

It is right to remember Partition with deep anguish, but it is also right to recall the hard-won independence that followed it. I think this is what Manto would tell us, were he alive today.

The most absurd thing about the extreme violence and destruction of Partition was the enormous, overwhelming hope that followed it. As Nehru said on 15 August 1947, “At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom.”

India will always be, at least to some extent, defined by hope; a sort of youthful enthusiasm for the future that seems to refresh itself with each new generation. That’s why this most recent flirtation with Hindu nationalism will be short-lived, and it is why Kashmir is sadly condemned to its troubles for many years more. In India, where there is anguish, there will always be hope. Perhaps not so absurd, after all.

Dr Kimberley Layton holds a PhD in international studies from the University of New South Wales, where her research focused on Hindu nationalism in the Indian diaspora. She is also a former AIIA Euan Crone Asian Awareness Scholarship holder and National Office intern.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.