In the Mirror Darkly: Considering the Attack on the Capitol through the Lens of Contemporary Radicalisation Literature

After the symbolically poignant attack on the US Capitol and a sitting Congress, it would be easy to rush policy decisions targeting the people responsible. While some may adopt emotionally charged or partisan responses, it is appropriate to lean on contemporary radicalisation literature to gain perspective.

It is difficult to consider the events of January 6 without a broader appreciation of the history of the radical right and the white supremacist movement in the United States. It may feel salient to point to Trump, to the rise of the alternative right, and to recent events in legislation and culture as adequate contest explaining why this event has occurred. However, there is nonetheless a deeper and more complex history to consider.

The events of January 6 occurred in a country which inspired the Nazi racial laws, emulating the earlier Jim Crow laws. They happened in a nation where, after Black Panther leader Fred Hampton was assassinated by the FBI in 1969, the Democrats and the Republicans supported David Duke’s election campaign, despite him being a leader of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. Despite attempts to reconstrue the story, there is a bipartisan inability to acknowledge the history of racial tensions in the United States. Without the reference point of a shared understanding of American history, it will always be difficult to facilitate discourse in an already divided nation.

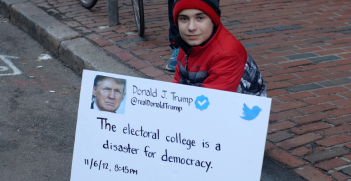

In 1983, the American radical right declared war on the United States of America at the Aryan World Congress. This marked a significant shift towards anti-establishment sentiment and action, including but not limited to the actions of the terrorist organisation The Order and paramilitary training camps organised by the KKK and other white supremacist groups. Pursuant to 1991, the end of the Cold War and the cessation of anti-Communist sentiment in American discourse saw this distrust of the government bleed into the growth of militias and the survivalist right, as well as contributing to events at Ruby Ridge and Oklahoma City. Until 2016 and the election of President Trump, the radical right maintained a feeling of being outsiders, which was a sentiment informing their susceptibility to radicalisation.

Radicalisation feeds off of perceptions and narratives of victimhood. While there is no correlation between socio-economic background and vulnerability to radicalisation and pursuant acts of violent extremism, there is correlation between perceiving a loss of stature and a vulnerability to radicalisation. It does not necessarily matter the physical attributes of a story. It matters how it is told, how it is held.

Through the election of the Trump administration, and the emergence of the pro-police Blue Lives Matter movement, the radical right found itself for the first time in a long time aligned with the government ideologically, and it identified with key legislative and executive decisions. Though the attack on the Capitol itself is an event of significance, we must also consider the threat that the pursuant reactions of the radical right pose, as well as the significance of the government’s response in the narratives that will be circulated around these events. Considering the work of McCauley and Mosalenko in their 2011 text, Friction, which assessed different pathways towards the activation and mobilisation of radicals, there are two key factors that we must consider in our analysis and commentary of the events and our predictions going forwards.

Jiu Jitsu Politics

First, let us consider the sensation of jiu jitsu politics as it pertains to narratives of radicalisation. The term, coined by McCauley and Mosalenko, describes a phenomenon in which a small group might provoke a larger one, often an establishment, into violent or aggressive action. This allows the smaller group to present itself as a victim and suggest that the repercussions of its own actions are unjust.

There will no doubt be copious books written about the role of President Trump in the events of January 6. However, it is also worth considering the key issue of assessing the actors’ motivation to invade the Capitol without present leadership from members of the state and establishment, which lends itself to a narrative in which members of the radical right were betrayed by their leadership and the elected state in their war against the establishment.

When a rally of actors affiliated with the radical right climbed walls and penetrated the Capitol, they set in motion a chain of events that must include government retribution, but that may not end there. The government response to the attack must be proportionate lest it provoke more individuals at risk of being radicalised to lend their weight in support of those who are punished for their actions.

Martyrdom

Second, we must consider the significance of stories. On the January 6, after being told to desist and refusing to, Ashli Babbitt tried to enter the chambers of the Capitol and was shot by Secret Service agents protecting members of Congress. Ashli Babbitt was a veteran that had survived four tours of duty. For four tours, she had prepared herself to die for her cause and country, and then, faced with the same choice at the Capitol, she chose to put herself in a position in which she might die for what we believed in. She did so.

There is a tradition in the United States of “throwing away” men and women who have served once they come home. Pursuant to the Vietnam War, former soldiers flocked to radical groups on the left and the right when they felt they had been forgotten. However much analysis may come about regarding the ideologies of Ashli Babbitt, how she was radicalised, and what these ideologies meant to her, what matters more now is that people will tell stories about her. McCauley and Mosalenko describe the significance of martyrdom as being not self-evident, but rather something that must be constructed in the public eye. It matters less now who she was than who she can be represented as, and who this new character can stand for.

Going forwards, it matters less who Babbitt and other characters that died on January 6 were, but what they will mean to the radical right. Already there are rallies being organised in the name of Ashli Babbitt that will call her a martyr. Unless alternative narratives can be offered through traditional media to those at risk of radicalisation, Babbitt’s death may yet be an electrifying moment for the radical right.

As we consider the actions of violent extremists and put our eye to radicalisation, we must strive to be able to look with sympathy, but never be sympathetic. We must understand, but never be understanding. The events of January 6 were unprecedented, but that does not mean they can be unmatched.

Benjamin Fincham-de Groot is a postgraduate candidate in international relations at Deakin University.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.