Challenges on the Move: Access to Education

The International Committee of the Red Cross is promoting the need to question the status quo and encourage the commitment of governments and international actors to providing services, including education, to displaced and migrant populations.

“Even as a child, I knew that education was the key to my future. So, when I fled Syria, the only belongings I took with me were my school books,” explains Muzoon Almellehan. Almellehan is one of the lucky ones; there are 263 million displaced children that may never again have access to education.

Millions of children struggle to access education when they are displaced. And regardless of their status as internally displaced people (IDPs), refugees or migrants, the children who suffer disruptions to their education are five times less likely to be later enrolled in primary or secondary school. In protracted crises, many of these children grow up without any education at all.

One of the foreign aid priorities for the Australian government is “providing access to education to the poorest and most marginalised children including in fragile and conflict affected states”. At Australia’s instigation, the MIKTA (Mexico, Indonesia, Republic of Korea, Turkey and Australia) partnership launched the Education in Emergency Challenge in 2017, which awarded $2 million to 7 winners to develop and test their innovative solutions to ensure access to education in emergencies.

The ICRC vulnerability approach

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) assists people affected by conflict around the world, including IDPs, refugees, asylum seekers and irregular migrants. The ICRC is primarily concerned by the vulnerabilities and needs of people on the move whose status can be changeable depending on the situation.

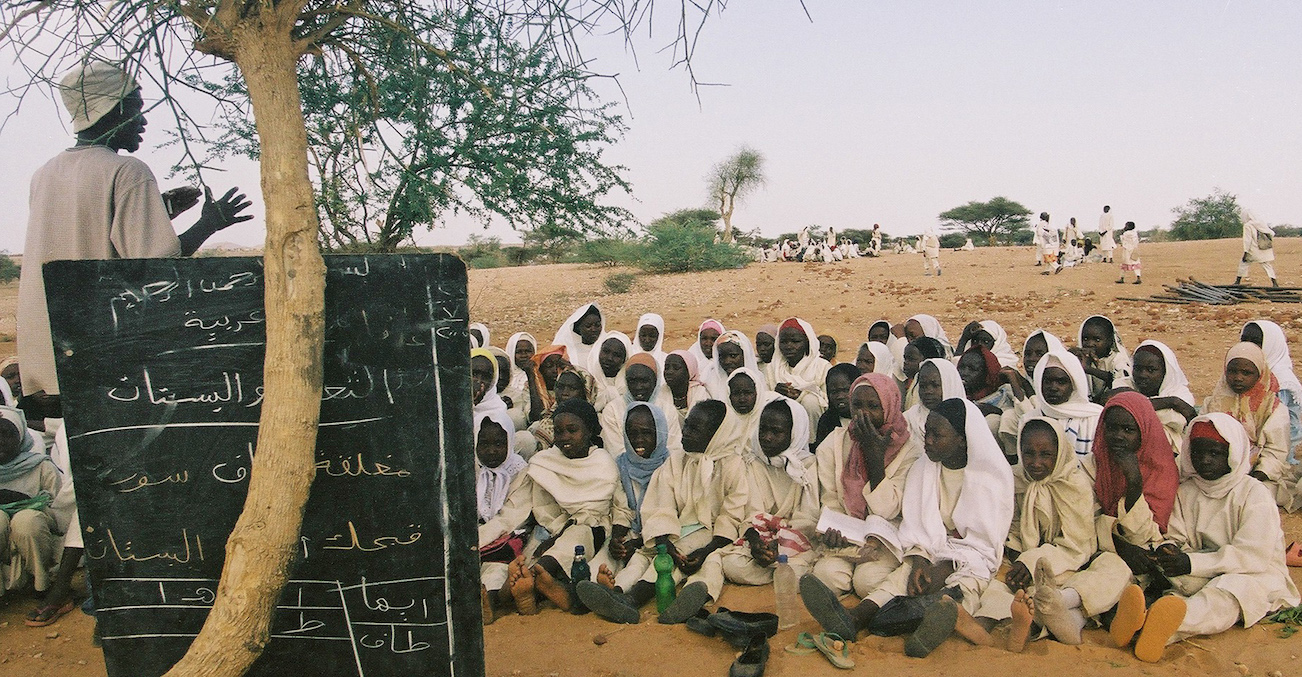

One vulnerability that the ICRC focuses on is access to education. Although education is crucial to secure stable and decent living conditions, children and young migrants often remain out of school simply because education is rarely accessible. The ICRC endeavours to integrate education-related activities in its humanitarian response to conflict situations. For example, education is often disrupted when school grounds are used as emergency housing or children are displaced far from their schools. The ICRC aims to find solutions to disruptions, such as erecting shelters to provide alternative housing or facilitating transportation for school children.

Obstacles and barriers

“Access to education does not mean only going to school or the availability of teachers… It means there is an environment within the family or community that can support the educational process,” says Salim Salama, a 25-year-old from Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp whose law degree was disrupted by the recent Syrian conflict.

Displaced people face a number of specific obstacles as they seek education. These can include basic survival, administrative challenges and the capacity of host communities. Displaced people lack access to living essentials, such as drinking water, food and adequate shelter. Unsurprisingly, these are usually prioritised over education. People on the move also lack economic security. As a result, children and youth often work to earn money to support their families instead of going to school.

Migrants who flee from conflict commonly lack personal identification and other official documentation. This creates an administrative barrier to education. In some cases, education may not be accessible to non-residents and many parents fear that revealing their children as irregular migrants could jeopardise their security.

The capacity of schools in host countries is a critical factor in whether children receive education. Attempting to find education in one’s own language, or even culturally appropriate education, can be ambitious for migrants. The psychosocial needs of displaced children who have endured hardship in their lives creates an additional challenge to find a suitable school where they can feel safe and comfortable to learn.

How to respond

Education is a high priority for refugees, asylum seekers, irregular migrants, and IDPs, but appears to be less so for governments and international actors.

Only 2 per cent of humanitarian funding is directly allocated for education. The humanitarian situation continues to deteriorate as millions of displaced children are uneducated. These children will remain invisible as they lack the tools needed to ensure financial security.

Host countries often lack the resources needed to ensure education for displaced people. Humanitarian organisations should therefore have access to the affected population so they can enable the provision of and access to educational facilities for displaced children and youth. Perhaps even more importantly, the public must question the status quo and encourage the commitment of governments and international actors to providing services, including education, to displaced and migrant populations.

The ICRC continues to engage with parties to conflict regarding their obligations under international humanitarian law, especially in relation to the rules protecting civilians and civilian objects, such as teachers, students and schools.

Otone Tatsumi is a student of policy studies at Kwansei Gakuin University, Japan, and is currently completing an internship with the International Committee of the Red Cross, Australia Mission.

Ahead of an upcoming issue of the International Review of the Red Cross on migration and displacement, this article is part of a series (see earlier posts, Going Missing and Legal Protections) examining some of the humanitarian challenges faced by people on the move, be they internally displaced, refugees or migrants.

This article is published under a Creative Commons licence and may be republished with attribution.