Humanitarian Irony: Avoiding COVID-19 Despite No Mask, No Soap, and No Hope

The pandemic has forced many of us to experience similar concerns to those living in armed conflict. Empathising with them helps the ICRC to shape a response that reflects its values.

How do you avoid getting coronavirus when you are sitting shoulder-to-shoulder with hundreds of strangers, with no cleaning or protective items, and no way to escape? From the safety of working from home, I think about people like Japhet*, a detainee I visited in the Democratic Republic of the Congo with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), who cracked his eyes open as light flooded into his crowded, unventilated cell. Japhet shared a single bucket with thirty others as a toilet, was allowed outside once per day for fresh air, and had no soap or running water.

The ICRC works for people affected by armed violence – think wars, tribal conflicts, and civil uprisings. I have been part of the ICRC’s Protection department since 2009, in contexts as varied as Sri Lanka, DR Congo, Colombia, and Niger. Protection teams focus on whether people’s rights are respected and whether armed or civilian authorities are fulfilling their obligations. Concretely, this means working to improve the treatment and conditions of people deprived of their liberty; mapping out and responding to the consequences of war on civilians; re-establishing contact between family members or seeking to clarify their fate; and advocating for the dignified management of the dead.

Armed violence may seem faraway if, like me, you are from Australia and have benefitted from security, education, and health services all your life. However, coronavirus has forced many of us to experience firsthand some of the daily concerns of people living in conflict zones.

Firstly, for both coronavirus and conflict, it’s not easy to understand what is going on. Information can be piecemeal, polarised, and politically charged, yet at the same time, crucial for making potentially life-saving decisions. Does “100 coronavirus deaths” mean coronavirus was confirmed, or suspected? Did people die with Coronavirus, or from Coronavirus? And how many cases are we missing? In conflict settings, the ICRC analyses similar information: who are the vulnerable, how are they affected, what is the cause, and what could be the best response. We talk directly to people on all sides of a conflict, and crosscheck internally with legal, military, medical, and other experts.

Understanding this information helps us minimise fear, manage uncertainty, and evaluate risks. We are all wondering whether physical distancing and wearing masks is effective enough to interact with others, or how risky coronavirus is compared to everyday occurrences like car accidents. Similarly, people affected by armed violence are constantly assessing risk factors: new armed groups, political changes, gunshots heard in the night… For many of these people, coronavirus is yet another threat to add to the menu of violence, poverty, displacement, and poor basic services. In the ICRC’s response, we strive to provide the information needed to assess risks and take action, whether it be public health messaging to help stave off coronavirus among displaced communities, or high-level discussions with authorities about respecting people’s right to seek asylum, even when border closures are being implemented.

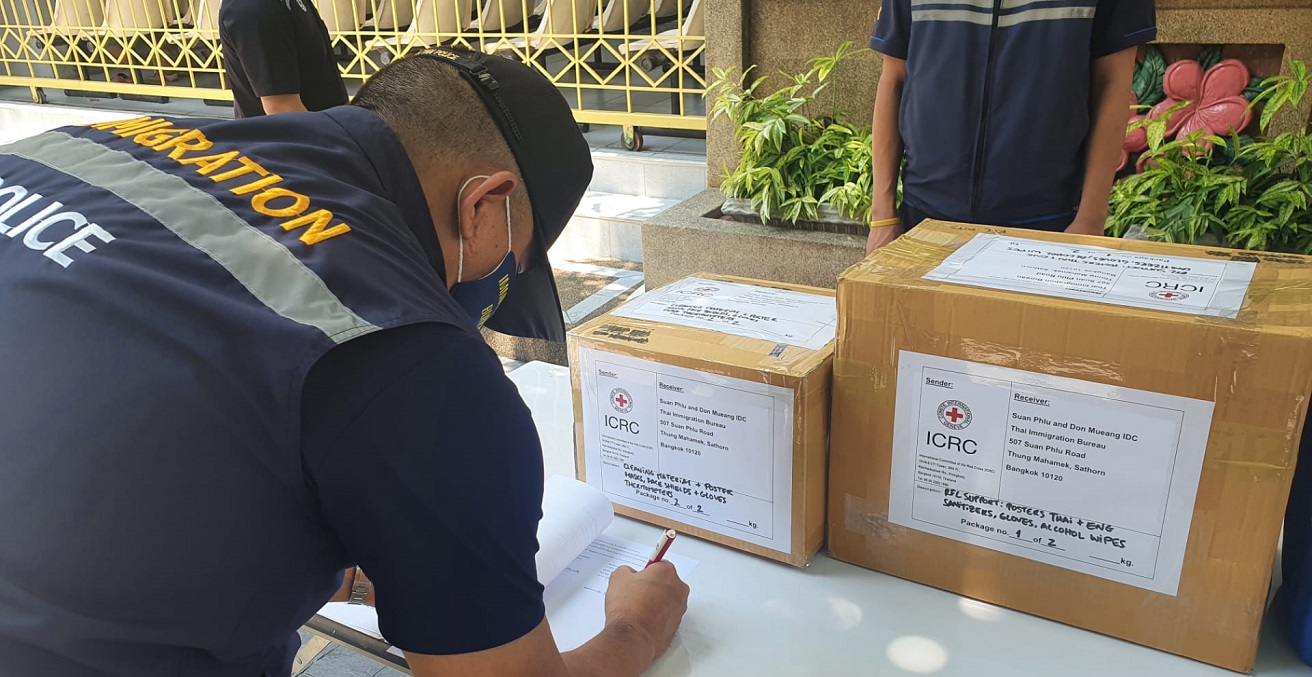

Conflict and coronavirus also demand that we prioritise what is important. I feel fortunate to have a home to be safe in, where social distancing is no challenge. Yet social distancing is not so easy for detainees like Japhet, living in decrepit facilities, migrants living in crowded ghettos, or people living under siege. The ICRC is helping vulnerable people and authorities to address these situations by preventing coronavirus from occurring in the first place, implementing hygiene measures, and supporting health services.

Family is the other key priority for me: as the pandemic sweeps across the globe, families have been rushing to their phones to check on the safety and wellbeing of loved ones. People do the same during outbreaks of armed violence. The ICRC works closely with the National Red Cross and Red Crescent societies worldwide to search for people who have gone missing. We facilitate phone calls or exchange letters to help people keep in touch. These activities are all the more important during restrictions of movement, transport shutdowns, or additional law enforcement measures, which we see in both conflict and coronavirus settings.

Finally, both crises force us to think about what kind of future we want. In times of strife, what are the overarching values we want to display? The ICRC is used to dealing with emergencies, analysing the context, and documenting good or emergent practice, while simultaneously deploying a response. This response is always guided by our core values: to show humanity to those who are most in need, regardless of who they are or where they come from. For coronavirus, we need to ask ourselves what health, economic, social, and political consequences will affect the most vulnerable in our communities, and what measures we are taking to care for them.

If we have the privilege of being in a home we feel safe in, to be in contact with our loved ones, and with some hand sanitiser nearby, then we are far more fortunate than Japhet was when I visited him. Just as we did not choose to be affected by this pandemic, others do not choose to be affected by violence. Recognising that we all have similar needs and concerns, we need to consider how the most vulnerable are affected by both conflict and pandemic, and how each of us can have a role to shape a collective response that reflects our human values.

* Name has been changed for privacy reasons.

Tanya Brown is the Regional Protection Trainer for Asia-Pacific with the International Committee of the Red Cross based in Bangkok.

This article is part of the “Conflict and COVID-19” series by the International Committee of the Red Cross in partnership with AIIA, highlighting the overlapping humanitarian fallout of war and pandemic. The views expressed above are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent those of the ICRC.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence, and may be republished with attribution.