Hong Kong Stands on the Brink of Change

Summary

A violent end to the protests in Hong Kong has been avoided, with crowds of pro-democracy demonstrators dwindling from peak turnout over the past two days. A few protests persist, but in the short term, most of the disputes will move to the negotiating table. Coupled with irreconcilable differences with Beijing, the protests could eventually bring Hong Kong, a city-state best known for order, stability and a welcoming business culture, to a turning point.

Analysis

For decades, Hong Kong was characterized by its vibrant civil society, liberalized economy and rule of law, features that were not always reconciled with traditional Asian culture. Although the city-state’s protest culture is rich, it is nonaggressive and nonviolent by nature. In many ways, protests in Hong Kong have not had much to do with the political authorities — neither the British colonial government nor the authoritarian power in Beijing — at least in the early years after the 1997 handover, nor have they been overly concentrated on political issues such as elections, voting participation or democracy. More fundamentally, Hong Kong’s protest culture is rooted in the city-state’s democratic values of free speech and the right to protest.

Moreover, Hong Kong’s population has a strong desire to preserve the qualities that set the enclave apart from mainland China: political autonomy, financial liberalization and relatively democratic institutions. This desire has grown more prominent over the past decade, during which Beijing’s political dominance and cultural and economic influence in the city-state have grown.

In recent years, Hong Kong has seen a rising tide of political polarization and, in some cases, radicalization among a demoralized democratic movement. The city-state is divided by frustrations over an influx of mainland investors and tourists and by ambivalence toward Beijing and its perceived limitation of Hong Kong’s freedom. Hong Kong is still known for its civility and stability. However, moderate actions such as marches and sit-ins are no longer seen as the most effective tools for advancing the political demands of a more progressive and independent democratic movement made up especially of Hong Kong’s youths. The new protest actions include mass street mobilizations and counteractions that paralyze commercial districts and government buildings. Hong Kong is a city-state with a growing identity crisis, and these more aggressive protest measures are feeding its political polarization.

What Has Gone Wrong in Hong Kong

There are several reasons for Hong Kong’s growing agitation. First are concerns about mainland China. Hong Kong’s population, feeling that Beijing’s political and economic domination is straining the city-state’s limited resources and space, is holding steadfast to its desire to preserve Hong Kong’s political autonomy, democratic values and resources. Not only is this rising antagonism between the mainland and Hong Kong divisive for the city-state’s indigenous political balance and society, but it is also giving rise to a political impasse between Hong Kong and Beijing. Controversies between the city-state and the central government have erupted over universal suffrage and the election of Hong Kong’s chief executive. Hong Kong’s democratic demands, particularly from the younger generation, contrast with what Beijing is willing or able to offer, despite the concept of “one country, two systems.”

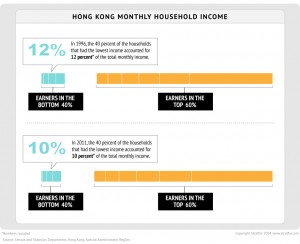

However, politics are not the only issue. Despite the growing wealth in the city-state since 1997, the past decade has given Hong Kong one of the highest income disparity rates in the developed world. Wealth and resources are concentrated among a small number of established business and financial magnates with strong political backing. Meanwhile, space is becoming scarcer, and opportunities for upward mobility for most of the public, particularly the youth, are declining.

The wealth aggregation seen in Hong Kong is achieved mostly through the manipulation of the land supply, which, combined with a staggering concentration of mainland capital inflow into the real estate sector, has led property prices to soar — nearly quadrupling over the past decade while median pay increased by only 10 percent. Many low-income and young residents of Hong Kong have become disillusioned as their hopes of buying a house were dashed and as much of Hong Kong became devoted to serving as a service hub and investment destination.

Without manufacturing and high-tech industry to drive economic development, Hong Kong relied on trade, finance and tourism — most of which came from the mainland — for more than 90 percent of its economy. Its reliance on the mainland created a paradox for Hong Kong: Without more self-driven development, the enclave will continue to depend on the mainland to generate wealth and employment, but the resulting integration reduces the distinctions between the mainland and Hong Kong that made the city-state competitive. Moreover, integration intensifies the identity crisis — and even reignites nativism — that drove Hong Kong away from Beijing.

One of the undeniable factors in Hong Kong’s decades of economic strength is its role as the major — if not the only — transport, trade and investment conduit between the mainland and the rest of the world. Its Western-style regulatory system, free port, liberalized economy and, of course, proximity to the Chinese economy all played a key part. Moreover, the central government granted Hong Kong fiscal, investment and political preferences to capitalize on the city-state’s position. These privileges reached their peak by the time mainland China emerged as an economic powerhouse. Hong Kong, which was a declining manufacturing base in the 1970s, became the world’s leading re-export and financial center in the 1990s and has maintained this status, surpassing many of its regional peers such as Taipei, Kuala Lumpur and even Singapore.

Nevertheless, the conditions that gave rise to such unprecedented success will eventually evaporate. For one thing, China is undergoing a political and economic transformation; for another, competition from mainland cities such as Shanghai, Shenzhen or Guangzhou is mounting. In the past two decades, Hong Kong’s gross domestic product as a share of the mainland’s GDP plummeted from 25 percent to 3 percent. Competition could increasingly limit Hong Kong’s re-export- and logistics-oriented economy. (The two economic areas accounted for 25 percent of Hong Kong’s GDP over the past five years.)