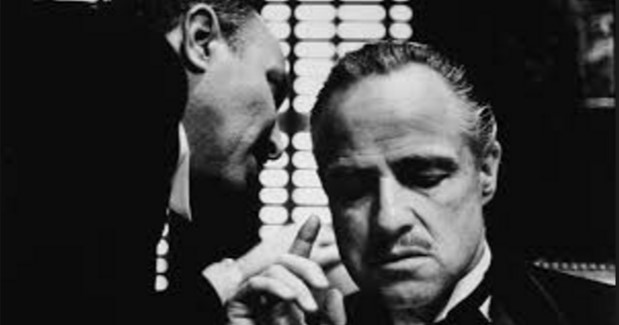

Hidden Power: Organised Crime in International Politics

All too often criminal mafias determine political outcomes by influencing elections, changing constitutions, fomenting terrorism, waging war and even negotiating peace deals when it suits them. Earlier this week, former Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott warned of the “potential for corruption” in the New South Wales Liberal Party, as power brokers and lobbyists grow increasingly close.

Concerns about corruption are a perennial factor in democracies. But we tend to assume that even if organised crime wields influence over government, that influence stops at the water’s edge.

Why? Given what we have learned from authors such as Misha Glenny about the globalisation of organised crime, and from analysts such as Moisés Naím and others about the convergence of criminal power and political power, is this assumption safe?

On the shores of Lake Geneva

In 1999 a former CIA director, Jim Woolsey, appeared before the Committee on Banking of the United States House of Representatives. He explained:

If you should chance to strike up a conversation with an articulate, English-speaking Russian in, say, the restaurant of one of the luxury hotels along Lake Geneva, and he is wearing a US$3,000 suit and a pair of Gucci loafers, and he tells you that he is an executive of a Russian trading company and wants to talk to you about a joint venture, then there are four possibilities. He may be what he says he is. He may be a Russian intelligence officer working under commercial cover. He may be part of a Russian organised crime group. But the really interesting possibility is that he may be all three—and that none of those three institutions have any problem with the arrangement.

Woolsey was warning that mafias, businesses and states were becoming difficult to tell apart. What does this mean for how we understand contemporary international affairs? My new book Hidden Power: The Strategic Logic of Organized Crime seeks to tackle this question. Drawing on unpublished government documents and mafia memoirs, Hidden Power explores a century of efforts by American and Italian organised crime groups, in Sicily, New York, Cuba and the Caribbean, to influence not only national but also international politics.

It reveals criminal groups influencing elections, changing constitutions, fomenting terrorism, waging war and even negotiating peace deals when it suits them. It uncovers the unrecognised role of criminal actors in the defence of the US eastern seaboard and invasion and of Italy during World War II, the Bay of Pigs fiasco and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

When criminal and political actors cooperate

These criminal groups rarely sought to assume political responsibility themselves. More typically, criminal strategy has involved the creation of political influence without political responsibility. Criminal actors seek to wield a hidden power.

As Tony Abbott’s remarks remind us, this does not necessarily mean that political and criminal actors will compete for political influence. On the contrary, the danger is precisely that they will sometimes cooperate or collaborate. Political actors can take formal responsibility for rule, while criminal actors wield influence behind the scenes.

Hidden Power identifies several different patterns that this accommodation between criminal and political actors seems to fall into.

Mafias—like those in Italy, America, and even Australia—typically pursue an intermediation strategy, brokering between upper-world political actors and difficult-to-access markets and populations. There are indicators of mafias emerging in numerous Asian countries. Political actors acquire money and votes; mafias receive power and protection.

In contrast, warlords and gang rulers adopt a different strategy—one of autonomy. Instead of sharing space with the state, like mafias do, these actors set themselves up as subsidiary rulers, sustained by control of informal and illicit markets. Afghanistan and Africa provide many recent examples.

In extreme cases criminal and political actors adopt a third, merger strategy, vertically integrating their organisations. In cases as diverse as 19th century New York, 20th century Palermo and Havana, and 21st century West Africa, criminal assets have been used to govern, and state assets to create criminal profits.

Confrontation

Sometimes, however, political and criminal actors confront each other in a competition for governmental power. Again, we see different patterns emerging.

Criminal groups may adopt terrorism as their strategy, intimidating the population into forcing the government to change policies that harm criminal interests. The Sicilian mafia did this in the 1990s, bombing politicians and prosecutors in an effort to stop state investigations. A case currently in the Italian court system is exploring whether the Italian state negotiated a deal with the mafia to end the violence.

In other cases, the criminal group may avoid confrontation by moving to another market—or even creating an entirely new one. In Hidden Power we see several examples of this, with the New York mafia kicked out of Cuba by Fidel Castro, mounting an unsuccessful armed invasion of Haiti, before developing a more fruitful collaboration with political rulers in the Bahamas.

Is criminal power growing in international affairs?

Perhaps most disturbingly, in some situations one set of criminal and political actors will team up to compete with another set of criminal and political actors. We saw different political-criminal alliances competing for power in New York in the 1930s. The question now is whether similar arrangements are emerging on the international stage

We appear to be witnessing a convergence between criminal strategies and the strategies of some state actors. As the Malaysian scandal around 1MDB shows, the line between visionary state-building and elite self-dealing can be perilously thin. Equally, some states—from North Korea to actors in Eastern Europe—appear to be using organised crime to achieve geopolitical and geo-economic effects designed to magnify their own power on the international stage.

In an era in which so-called state capitalism is an increasingly acceptable template for statecraft, the line between neo-mercantilism and transnational organised crime may grow even more blurred. As Jim Woolsey and Tony Abbott both pointed out, that may suit not only the criminals, but also some political actors.

Their gains will inevitably come at the expense of someone else: the global public.

Dr James Cockayne is a strategist, international lawyer and author. He is head of office at the United Nations for United Nations University, a global think-tank created by the UN General Assembly.

Hidden Power: The Strategic Logic of Organized Crime (Hurst/OUP, 2016) will be published in early September in the UK. It is available for sale on Amazon or through the publisher’s website.

The article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.