Here We Go Again? Electoral College Reform

For much of American history, the Electoral College, a product of 18th-century skepticism towards democracy, has simply been a quirk of the presidential election process. With direct democracy now broadly accepted, the Electoral College is actively undermining the democratic process in the US.

In 1845, Congress fixed Election Day to the first Tuesday of November. November was conveniently placed between harvest and winter, while Tuesday gave America’s mostly agrarian population a day to travel to polls after church on Sunday. They could arrive, vote, and then stay for market day on Wednesday. Almost two centuries on, Americans still vote on the first Tuesday of November. However, in recent years, post-election Wednesday is better known for demands to reform the Electoral College.

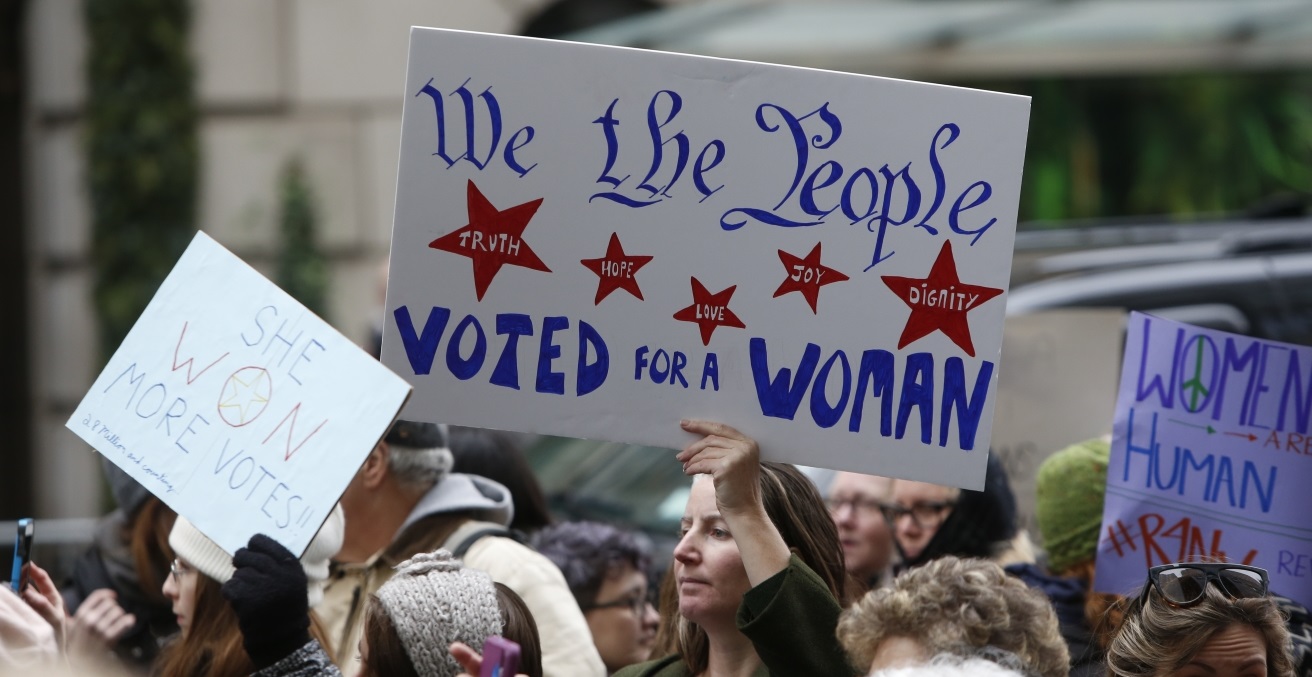

This election is no different. Since the election, various voices have called for the college to be abolished or reformed. Were residents elected by popular vote, Biden’s more than five million vote lead would make Trump’s current legal shenanigans almost impossible.

The Electoral College was the result of the founding fathers’ skepticism of direct democracy, and a constitutional compromise made with slave-owning states. Presidents were not to be elected directly. Instead, voters would elect party representatives called electors, and it is they who cast the votes that decide the presidency. Today, they number 538, and 270 votes are needed to win. Not foreseeing the rise of political parties, which the founders disliked, the hope was for the president to be chosen through sober and impartial deliberation amongst the country’s elite. Today, electors are neither impartial nor elite. Almost all are low-level party functionaries who can be relied on to vote as they are told.

Each state has electors equal to the total number of their senators and representatives; Washington, D.C. also has three. Since each state has two senators and at least one representative, sparsely populated states have proportionally more electors than more populous states. For example, one Electoral College vote is cast per 254,000 North Dakota residents, whereas in California, the ratio is one per 718,000.

Forcing candidates to win majorities across a broad swathe of the country was intended by the founders to counter majoritarian rule from populous urban areas. Today, population growth and urbanisation are creating the threat of minoritarian rule, as a shrinking proportion of the population maintains political power. According to the Wall Street Journal, by 2040, a third of the population will elect 70 percent of the Senate. Since Senate seats also grant electors, this system disproportionately empowers rural white voters.

One quirk of the system is that sometimes, presidents who lose the popular vote still win elections. This has happened five times in history, in 1824, 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016. In 2000, 537 votes in Florida delivered Republican George W. Bush the needed Electoral College votes despite Democrat Al Gore being more than 500,000 votes ahead nationally. In 2016, less than 100,000 votes gave Donald Trump the win, despite Hillary Clinton’s 2.8 million vote lead nationally.

It could happen again. Short of an outright coup, Trump’s most likely pathway to overturning Biden’s win would involve getting state legislatures in Republican-controlled states like Georgia or Pennsylvania to declare a “failed election” and select the electors themselves, a right granted to them under an 1876 law. The legality of this move would almost certainly be contested, but for reformers, it is exactly these kinds of quirks that could be avoided by replacing the Electoral College with a direct presidential election.

Democrats are typically associated with calls to reform the College, but support for reform tends to track electoral performance and parties that win tend to deprioritise reform. Democrats were loudest on the issue after 2000 and 2016. Republicans have toyed with the idea over the years, most recently after Obama’s election in 2012, where Donald Trump called the Electoral College “a disaster for a democracy.” With Biden’s win looking certain, some of the impetus for reform may fade.

Three major reform options exist. The first would replace the Electoral College with a direct popular presidential election. This would require a constitutional amendment, which must be approved by two-thirds of Congress and the states, a difficult proposition in partisan times. The last time an amendment was passed was in 1992 and concerned Congressional salaries. A less radical proposal would assign electors proportionally based on the results of the state’s popular vote. Today, almost all electors are assigned on a winner-takes-all basis. A third avenue, currently used in Maine and Nebraska, assigns two electoral votes to the winner of the state’s popular vote, while assigning the rest – two in Maine and three in Nebraska – to whoever wins the popular vote in each of the state’s congressional districts.

Electoral College reform enjoys considerable public support. A Gallup poll conducted in September 2020 showed 61 percent of Americans support replacing the Electoral College with a popular vote, although this support is increasingly split along partisan lines. 15 states and the District of Columbia have already signed a National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, promising to award their electoral votes to the winner of the popular vote. To date they have mostly been Democrat strongholds.

Assuming Biden takes office, what happens next depends on the ability of Democrats to pass reform, which means taking control of the Senate. Currently, Republicans hold 50 of the Senate’s 100 seats. Democrats sit at 48. The remaining two, in Georgia, will be decided in run-off elections in January. If Democrats win both, they would equal Republicans in the Senate. In the event of a tie, the vice president casts the deciding vote, giving Democrats the possibility of a majority. This would open up the possibility of institutional reform, including changes to the Electoral College, expanding the Supreme Court, or ending the filibuster – long targets of progressive Democrats. Should Republicans maintain control of the Senate, Electoral College reform will be placed on hold, along with most of the Democrat agenda, until the mid-term elections in 2022.

Lewis Jackson writes about economics and politics with a special interest in international politics and central banks. He has a Masters in Public Policy and Political Economy and worked as a management consultant for several years. You can find more of his writing here.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.