Hanoi's Internal Divisions Hinder Its China Policy

Summary

Vietnam is struggling with how to respond to maritime expansion by China and the resulting tensions in the South China Sea. Some of the strategies used by China have included counterbalancing China by cultivating relationships with regional and outside powers and trying to reduce China’s economic leverage against Vietnam. Until recently, the Vietnamese leadership’s tendency to prioritize a cordial relationship with China often offset such strategies — any major rupture with Beijing could expose uncomfortable internal divisions within Vietnam’s ruling Communist Party. Eventually, however, Hanoi will have to reorient its diplomatic, economic and political priorities to deal with China’s rise — a process that could reshape Vietnam’s internal politics.

Analysis

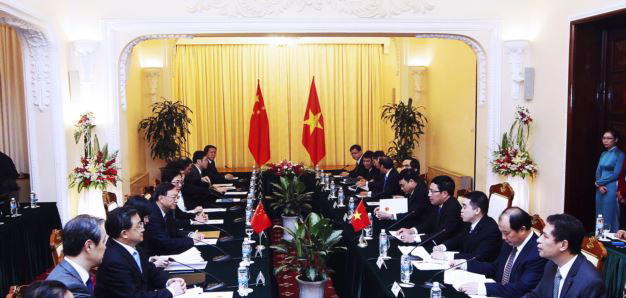

Bilateral tensions between China and Vietnam have become more pronounced since Beijing began pushing its maritime boundaries. China’s most recent aggressive move — the placement of deep-sea oil rigs near the Paracel Islands, which Hanoi also claims — appears to have prompted some unusual responses from Vietnam’s public and top leadership.

Hanoi’s answers to Chinese advances have included stationing maritime enforcement ships around the rig, but Vietnam has been extremely cautious about directly confronting China’s larger and more advanced coast guard and fishery vessels. Meanwhile, Vietnam’s attempt to resort to nationalism domestically fell short after deadly riots broke out in factories, undermining Vietnam’s investment environment and raising concerns about external forces manipulating the protests. Vietnam has also considered legal measures to counter China’s maritime claims, possibly under the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, which China had refused to participate in. While none of these responses will alter Beijing’s determination to exclude Vietnam from the Paracels, Vietnam appears to be seeking a long-term strategy to hedge against China’s intent to undermine Vietnamese territorial claims in future maritime disputes.

Vietnam’s Hedging Strategy

Among the key components of this hedging strategy are neutralizing Vietnam’s own bilateral maritime disputes with the Philippines; finding a common position on China with the rest of the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations; and forging closer security ties with the United States and regional and outside powers, including Japan, India and Russia.

Shortly after the tensions erupted over the oil rig, Philippine President Benigno Aquino III and visiting Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung in a rare joint statement demonstrated their solidarity by denouncing China’s maritime moves despite their own disagreements over the Spratlys. Vietnam has also approached Japan and India in an effort to step up maritime interactions, with the former emphasizing cooperation on coast guard and navy operations and the latter on long-delayed joint natural gas exploration. Most important, Hanoi is apparently interested in expanding its relationship with the United States following a series of high-level discussions. According to Stratfor contacts, one specific request recently from Vietnam has been for Washington to lift its ban on arms sales to Hanoi.

Meanwhile, as bilateral tensions with Beijing reach new heights, Hanoi increasingly views its economic reliance on China, once key to national development, as a liability. Vietnam’s own estimates indicate that tensions with China could slow Vietnam’s gross domestic product growth by roughly 1 percent from its original forecast of 5.4 percent. China is still Vietnam’s most important economic partner because it supplies much of the critically needed low-priced raw materials, machinery and equipment for Vietnam’s export-oriented economy.

Beijing has reportedly barred its state-owned enterprises from bidding on new contracts in Vietnam. While the impact will be limited given China’s relatively small stake in Vietnam’s investment picture (around 3 percent), the risk to Vietnam’s economy amid deteriorating relations — or even a small-scale ban on exports of certain raw materials and processing products from China — is forcing Vietnamese authorities to reconsider the reliance on China. Nonetheless, in the short term, this means Vietnam will struggle to reduce its reliance on relatively cheap supplies from China and diversify to often more expensive suppliers such as South Korea, Thailand or Indonesia.

Reshaping the Balance

Long-term strategies notwithstanding, the tensions with China appear to have aggravated conflicts between Vietnam’s top Party and government leaders over how to deal with Beijing. Notably, the prime minister’s high profile during anti-China demonstrations and efforts to ratchet up international pressure seem to have failed to gain support from the top political leadership. Party Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong, a prominent ideological leader believed to be one of the prime minister’s key rivals, and Defense Minister Phung Quang Thanh both called for prioritizing direct communication with China. The prime minister himself criticized the move to crack down on anti-China protesters, another example of the divisions within the leadership.

In recent years, Hanoi’s often contradictory approach to dealing with China’s territorial threat was in part a result of its historical experiences and geographic proximity to China. It was also a reflection of its delicate intra-party factional balance under the Communist Party’s collective leadership. This balance was characterized not only by its largely even power distribution among the four top positions — the president, Party secretary, prime minister and to a lesser extent the chairman of National Assembly wield roughly equal power — but also among the various geographic and ideological factions within the Party.

To some extent, Vietnam’s hourglass-shaped geography has contributed to the tendency toward relatively dispersed power networks since reunification in 1975. This was often compounded by the absence of a single strong leader and the near-constant warfare, occupation and insurrection the country experienced during the 20th century — a history that required it to capitalize on, balance against and fend off various external powers.

Party Politics

Shortly after reunification, Vietnam’s internal competition was primarily between those affiliated with the Soviet Union’s economic, political and security policies amid the dual threat of China and isolation from the West, and those who backed China’s revolutionary model, though that faction was weaker at the time. The closing years of the Cold War coincided with the country’s economic liberalization in 1986, which strengthened those willing to emulate China’s model of liberal economics and closed politics.

But as economic reform proceeded, it also greatly expanded the influence of Party members from southern provinces. They had previously been sidelined for their capitalist tradition and more liberal ideology in the largely northerner-dominated political elite. As the Party has gradually moved away from the ideological debate over the years, it has brought economic liberalization, the state’s role and regional competition between China and the United States to the fore of Communist Party factional politics.

Conversation: East Asia Flies Under the Radar

The current balance is largely split between the liberal camp led by Prime Minister Dung, whose power base encompasses business connections, pro-Western factions and officials from southern provinces, and the conservative camp, most prominently Party Secretary Trong, which is economically and ideologically more affiliated with China and made up of Party members from the north and the military. But recent years have also seen the rising influence of officials from central regions or those campaigning for balance between China and the United States. Serious infighting has emerged over the issues of changing Vietnam’s officially socialist ideology, privatizing state-owned enterprises and embracing a more Western political system. The competition went as far as an attempt to oust Dung as prime minister over his failure to manage Vietnam’s economic troubles and massive corruption in state-owned enterprises.

The harsh crackdown against anti-China protests has signaled an urgency to restore the country’s social order and appears to have given a voice to those who oppose sharp disruption in Sino-Vietnamese relations. Nonetheless, since China’s maritime expansionism is only beginning to take shape, the fear of long-term threats from China will regain its traction as Hanoi starts to reorient its diplomatic, economic and political priorities for the next National Congress in 2016. How the orientation evolves will depend largely on how the balance of power is struck among Communist Party factions. There appears to be a relative consensus within Vietnam’s leadership to hedge against China’s influence, which will mean either neutralizing those pro-China factions or completely reshuffling the existing balance of power within the Party in the next two years.

This article was originally published by Stratfor Global Intelligence. It is republished with permission.