Handshakes Hide PNG-Australia Tension

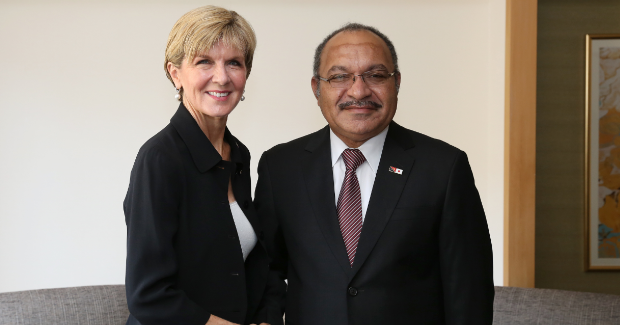

Julie Bishop’s recent visit to Papua New Guinea marked another seemingly stable chapter in Australia’s dealings with the Pacific nation. But the visit’s handshakes and smiles masked increasing strain on the historic relationship.

During her recent visit to Papua New Guinea (PNG) Minister for Foreign Affairs Julie Bishop co-chaired the 25th Australia-PNG Ministerial Forum, co-chaired the annual Australia-PNG Business Dialogue, celebrated International Women’s Day, opened Australia’s new Consulate-General in Lae and inspected what is currently Australia’s largest development project, the redevelopment of the ANGAU Memorial Hospital in Lae.

During the tenure of the Howard government, relations between PNG and Australia reached a low point—not least due to Prime Minister Howard’s and Minister for Foreign Affairs Downer’s insistence on referring to PNG as a “failing state”. However, relations recovered following the election of Kevin Rudd and have remained cordial under the present Australian government. Bishop has demonstrated a personal interest in PNG, which has been appreciated in the country. But for Australia, relations between the two countries require continuing careful management.

Atypical relationship

A major aspect of this relationship concerns Australia’s development assistance to PNG. At the ministerial forum, PNG’s natural planning minister Charles Abel reiterated the call for ‘”trade not aid”, asking for a mutually beneficial trade and investment partnership with Australia. But even if this can be achieved, aid is likely to remain an important element of the relationship. At present, Australia provides about $550 million per year in total development assistance to PNG, including $477 million through its bilateral assistance program. It mostly comprises specific programs negotiated with the PNG government within the framework of PNG’s planning structures.

The fact that some of this aid money is paid to Australian contractors and consultants has long been a source of resentment amongst PNG citizens, who often refer to Australia’s assistance as ‘boomerang aid’. In 2015 Prime Minister Peter O’Neill, arguing that foreign workers were making local staff lazy, announced that the contracts of all foreign advisers seconded to the PNG government would be terminated and a number of Australian public servants would be deported, reportedly over “fears they were spies for Australia”.

It is sometimes pointed out that in the early post-independence years, Australian aid to PNG was paid as direct budgetary assistance. This month, PNG suggested—not for the first time—that aid should again take the form of direct budget assistance. Specifically, PNG sought direct Australian funding for health and education after falling commodity prices and consequently reduced revenues forced the PNG government to make substantial cuts to spending.

The historical reference overlooks two important facts: first, in the early post-independence years Australia provided a large part of the young country’s budget (initially over 40 per cent) and it would not have been practical to deliver this as program aid; second, although it was paid as general budgetary assistance, Australia was in close contact with PNG officials concerning putting together the budget and monitoring expenditures, so there was some oversight of how money was spent.

Fresh challenges

The situation is now different. As it is, Australia’s development assistance programs are negotiated with PNG and are intended to align with PNG’s priorities. With respect to PNG’s interests, there may be a role for outside contractors and consultants. Working alongside PNG counterparts, they can provide expertise not readily available locally and are less susceptible to the pressures of local politics, which have often seen funds diverted away from planned targets.

PNG’s request for direct budgetary assistance reportedly came as a surprise to the Australian ministerial delegation. Bishop did, however, promise to consider it, while noting that any change to the aid program would need to meet Australia’s accountability standards. The delivery of development assistance to PNG is likely to remain challenging.

Another important item on the ministerial forum’s agenda was the Manus refugee-processing centre. Relocating asylum seekers to Manus was never a good idea. Leaving aside moral questions about shunting Australia’s problems onto its neighbour, it has predictably become a source of problems for both PNG and Australia.

In April 2016, the PNG Supreme Court found the Regional Resettlement Agreement between Australia and PNG unconstitutional. The extraordinary response of Australia’s Minister for Immigration and Border Protection Peter Dutton was to gratuitously offer to assist PNG to redraft its constitution. Ignoring this, Peter O’Neill announced the centre would close and the Australian government would be asked to make alternative arrangements for the asylum seekers housed there. The Australian government, however, ruled out the possibility of accepting any of the asylum seekers from Manus. With some 800 asylum seekers still on Manus and the PNG government threatened with contempt of court proceedings due to its failure to carry out the court’s ruling, there is growing frustration over this issue. It has the potential to cause tension in relations between the two countries.

Beyond the issues raised—and amicably discussed—during the ministerial forum, there are larger issues bearing on Australia’s relations with PNG. For one, in recent years and particularly under O’Neill, PNG has aspired to a greater leadership role among Pacific island nations. This has occurred specifically through the Pacific Islands Forum and the Melanesian Spearhead Group, but also at wider international forums.

Even aside from Fiji’s efforts to downgrade Australia’s and New Zealand’s role in Pacific regional politics, it has become increasingly clear that the interests of the island states and territories—on issues such as the PACER Plus agreement, West Papua and climate change—are not necessarily those of Australia. Moreover, while PNG talks about a mutually beneficial trade and investment relationship with Australia, it looks increasingly to Asia. Against this background, Australia’s capacity to influence PNG government policies appears to have declined.

Further, while Julie Bishop has recently spoken of the importance of democratic institutions with specific reference to China, Australia has had little to say about what many people within and outside PNG see as undemocratic tendencies and poor governance in the country: ranging from ignoring Supreme Court rulings, avoiding votes of no confidence, disbanding the anticorruption Taskforce Sweep and passing legislation to authorise action against social media critics of the government, to threatening the ombudsman commission and raising international loans without obtaining parliamentary approval.

Clearly, O’Neill still has strong support within the parliament and may well be returned as prime minister after the national election in the middle of this year. He is a smart politician with whom Australia could work in the past. However, given growing domestic criticism of the prime minister, evident from social media and other sources, one might wonder if a close and largely uncritical relationship with an O’Neill government is in Australia’s long-term interests.

Though the visit of the Australian foreign minister and her colleagues appears to have been a success, the path ahead may not be smooth.

Ronald May is an emeritus fellow at the Australian National University. Earlier in his career he was senior economist with the Reserve Bank of Australia, field director of the ANU’s New Guinea Research Unit, and foundation director of what is now the National Research Institute (NRI) in Papua New Guinea.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.