Growing Threats of Violent Extremism: The Urgency for a Gender-Based Response

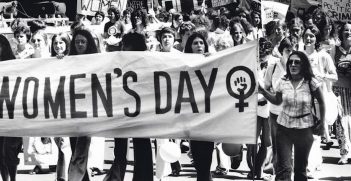

The recognition that gender identity and ideology are connected to threats of violent extremism is now the subject of a growing body of policy and evidence. Prevention strategies should take into account the gendered dimensions of radicalisation and recruitment to violent extremist groups.

In his first ASIO Annual Threat Assessment address, the Director-General of Security Mike Burgess elevated the threat posed by right-wing extremism in Australia. In light of the March 15, 2019 Christchurch attack that killed 51 people, this comes as little surprise to Australians. Specifically, Burgess noted that the “extreme right-wing threat is real and is growing” and that “extreme right-wing online forums such as The Base proliferate on the internet… encourage and justify acts of extreme violence.” However, the address also made reference to “gender” ideology in the risk scenario for the first time, stating that “intolerance based on race, gender and identity, and the extreme political views that intolerance inspires is on the rise across the Western world in particular.”

The 2015 UN Global Study on the Implementation of Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) raised the issue of rising cultural and religious fundamentalisms affecting women’s security and rights. It noted the connections between the Counter-Terrorism/Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) and WPS agendas. Resolution 2242 explicitly linked these agendas by stressing the need for a gender perspective on the prevention of violent extremism (PVE) and opportunities for women’s participation. In recent Monash Gender, Peace and Security Centre research with UN Women in Asia and North Africa in four countries, we found that more than any other factor, including religious ideology, relative poverty, and education levels, support for violence against women was strongly associated with support for violent extremism. Furthermore, we also found that in the context of Bangladesh and Indonesia, that engaging women in community initiatives on PVE and CVE increased their knowledge and confidence to respond to violent extremism at home and in the community and to report incidents that might be warning signs of violent extremism.

This research provides a foundation for research and action, as does recent international guidance on women and CVE, but there is much more to be done. Crucial to investigate are the online forums that are spreading extremist ideologies and justifying violence by explicitly appealing to ideal male and female gendered identities and promulgating extremist, gendered ideologies about men’s and women’s proper roles. These gendered dimensions of radicalisation and recruitment to violent extremist groups should be informing current countering and prevention strategies in all countries, including Australia’s. Few interventions, for example, have explored how online and offline gendered counter-messaging through counter-narratives can prevent recruitment by challenging or disrupting the gender roles and norms of women and men in extremist organisations.

A gender-sensitive approach to countering violent extremism is urgent given the probable threat level. The last Independent National Security Legislation Monitor Annual Report (2018-2019) noted that although Brenton Tarrant conducted the Christchurch mosque attacks alone, he drew inspiration from a global network of like-minded individuals. While attacks by far-right extremists are not new, Christchurch “turned into a seminal event in the history of such terrorism for its lethality and technology to maximise impact, in particular the live streaming of the attacks on social media.” Yet the misogynist, racist, bigoted, and homophobic grievances in Tarrant’s “The Great Replacement” manifesto that condemn “the decline of fertility rates and destruction of the traditional family unit” have hardly been analysed. The racialised, gender ideology underpinning this manifesto is explicit. It reveals a radicalised, gender identity as integral to violent extremist beliefs. Based on our research, we argue that gender analysis holds utility in understanding the factors that can facilitate, sustain, and spread violent extremism. It is imperative that we understand how constructions of masculinities and femininities can drive radicalisation, influencing and reinforcing gendered language and online-messaging, and specific recruitment targeting of women and men.

Currently, we are examining gender constructs in extremist groups in Australia. We have found that among far-right extremist groups, gendered messaging is pervasively used. Such messaging is directed towards both women and men. It suggests the types of distinct roles that they should play in supporting the movement, particularly in terms of supporting the strategic and operational objectives of the group. One group explains that a real Alpha male should remain physically fit in order to “protect his current or potential female partner and children from all aggressors and foreign invaders,” closely linked to broader far-right extremist ideology that tends to promote the need for “protection” vis-à-vis outgroups. More than this, however, we have identified specific gendered themes in the online content of far-right groups. For example, some messaging casts women as being the “reproducers” of the white race and to strong men as the “protectors and guardians for his family and race.” They also suggest how they should “act” in the movement. For example, one far-right group explains that women within the movement should focus on self-improvement, be fit and healthy, and develop skills and education. They should also seek to find honourable men that share the same values, and that they are tasked with “building a strong empire- a strong family.” Another far-right group emphasised men’s roles as the “leaders” of women and children. Strikingly, in far-right groups, we found that ideological constructs linked to the fight to “protect” were often linked to traditional gender norms and deliberate appeals to paternal and maternal instincts.

Although it is clear that the “extreme right-wing threat is real and growing” in Australia, Europe, and the United States, what is also real is that gender dynamics — not just political, religious, socio-economic dynamics – are specific tools of radicalisation. There is thus an urgent need for sharing knowledge, intelligence, and evidence-based research on the gender-specific drivers of violence extremism by country, and to improve the gender-sensitivity of risk assessments for violent extremism and terrorism. Together with other researchers, civil society organisations, and governments in our region and globally, we need to be able to identify the gender-related trends in violent extremist groups, as well as the policy and societal shifts that give early warning of violent extremism and terrorism, to be able to effectively respond to their threats.

The search for peace and security requires new thinking. Australia’s second National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security, to be launched shortly, is an opportunity to address the key gaps in security efforts and to enable gender-based approaches, which serve as frontline defenses against violent extremism and terrorism in our community.

Dr Alexandra Phelan is a Lecturer in Politics and International Relations at Monash University. She leads the gender and violent extremism research stream at Monash GPS.

Dr Melissa Johnston is a Postdoctoral Fellow at Monash GPS, where she leads the research stream on inclusive economies and enduring peace.

Professor Jacqui True, FASSA, is the Director of Monash University’s Gender, Peace and Security Centre. She is an Australian Research Council (ARC) Future Fellow and Global Fellow, Peace Research Institute (PRIO) Oslo.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.