Greece's New Government Faces Serious Discord Over Debt

While the 25 January elections represent a widespread rejection of austerity measures in Greece, reversing these policies will be easier said than done.

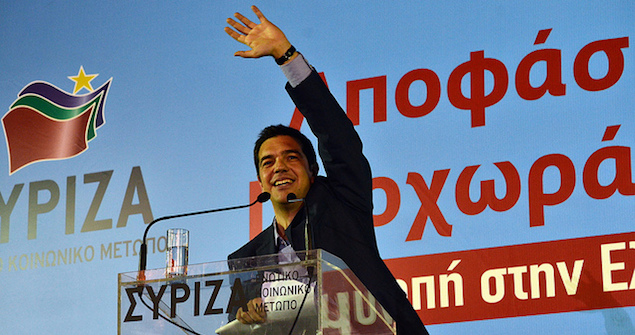

After receiving 36.3 per cent of the vote in Greece’s 25 January elections, left-wing Syriza party reached an agreement on 26 January to form a government with the right-wing Independent Greeks party, which received 4.7 per cent of the vote. This agreement makes Syriza leader Alexis Tsipras the new Greek prime minister. Syriza will push to reverse some of the previous governments’ austerity measures, applied under pressure from the European Union and the International Monetary Fund. More important, it will propose a renegotiation of Greece’s debt.

The alliance with the Independent Greeks, which includes former members of mainstream parties and takes a tough stance on immigration and foreign policy, may prove uncomfortable for many members of Syriza, but it puts in charge two parties that are willing to pursue a hard line on debt negotiations with Brussels. With most Greek voters supporting the country’s membership in the eurozone, Syriza will not make any unilateral moves regarding Greece’s debt, preferring an agreement with the European Union. However, Brussels is unlikely to accept a new write-down of Greece’s debt, a reality that will push the two actors further toward collision. The first test for Athens will come as early as February, with the beginning of a long series of debt repayments.

Six years into the European crisis, most Greeks have voted against parties that, to different degrees, oppose the policies designed by the European Union and applied by establishment political parties in Athens. Syriza’s victory in the 25 January elections, as well as electoral gains made by protest parties such as the centrist To Potami (which got 6 per cent of the vote) and the far-right Golden Dawn (which got 6.3 per cent), mark a turning point in Greek history with the defeat of its traditional elites.

Since the end of Greece’s dictatorship in the mid-1970s, outgoing prime minister Antonis Samaras’ center-right New Democracy and the center-left Panhellenic Socialist Movement, or PASOK, have dominated Greek politics. But the European crisis changed this setting: in 2012, New Democracy and PASOK were forced to form an alliance to remain in power. On 25 January they were defeated by anti-system parties. New Democracy came in second with 27.8 per cent of the vote, while PASOK barely made it into parliament with 4.7 per cent.

The elections represent a widespread rejection of austerity policies in Greece. During the campaign, Samaras promised to gradually soften the policies in place since Greece received its first bailout in 2011. He also warned that a Syriza victory would push Greece to the brink of leaving the eurozone. Such threats were not enough to convince Greek voters, who, facing a six-year recession and an unemployment rate above 26 per cent, decided to vote for a party that promised a change of direction.

A New Political Phase Begins

Syriza’s victory opens a new political phase in Greece. The party campaigned on a reversal of the austerity policies applied by previous governments. Tsipras promised to raise the minimum wage, subsidise electricity and health care for the poorest households and restore the extra “thirteenth month” payment given to those who receive the lowest pensions. More important, he promised to renegotiate Greece’s sovereign debt, which currently represents roughly 175 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product — the highest ratio in the European Union.

Most of this will be easier said than done. Syriza has said its “emergency plan” will cost 12 billion euros (US$13.5 billion), which it said will be raised from renegotiating Greece’s debt, redirecting EU funds and fighting corruption. But none of these funds will be available overnight, and Greece will struggle to turn to debt markets without external support from the European Union and the International Monetary Fund. Greece cannot currently fund itself on debt markets because its borrowing costs are too high. Furthermore, the European Central Bank temporarily excluded Greece from its quantitative easing program on 22 January.

As a result, the new Greek government will have to make critical decisions within a short period of time. Greece’s bailout program officially ends on 26 February, and without a new agreement, Athens may not receive the final tranche of 7 billion euros. Greece certainly needs the money: in 2015, Athens will have to pay some 22 billion euros in principal and interest on various loans, including 1.6 billion euros in February and 2.6 billion euros in March. Then, Greece is scheduled to pay back debt obligations of 1.5 billion euros in June, 4.7 billion euros in July and 3.6 billion euros in August — in addition to financing the country itself.

Syriza has said it plans to finance its government by issuing Treasury bills, or short-term debt, which the Greek banks would buy. But Greece has already reached the issuance limit for its Treasury bills. And without a formal agreement with the European Union, the European Central Bank could also stop financing the Greek banks. The European Central Bank currently exempts Greek banks from requirements on the collateral it accepts for access to funding, but the institution has said the continuation of this mechanism depends on the evolution of Athens’ relationship with its lenders. In addition, Athens has reported that tax collection declined in recent weeks, meaning that the new Greek government will have to more carefully examine the state of its tax coffers before making significant policy decisions.

Tough Negotiations Ahead

EU officials have sent mixed signals to Greek voters. On the one hand, they have said Brussels is interested in keeping Greece in the eurozone. On the other, they have requested Athens not to abandon the path of fiscal consolidation. Syriza has also sent mixed signals, promising to renegotiate Greece’s debt without leaving the eurozone.

Syriza is unlikely to make any unilateral moves on the debt front. Opinion polls show that most Greeks want their country to remain in the eurozone, and Syriza will probably decide to negotiate with the European Union and the International Monetary Fund before making any concrete moves. Should Greece unilaterally default on its debt, markets could panic and trigger a bank run. The European Central Bank could also decide to stop supporting Greek banks and force Athens to leave the currency union. These factors will likely force Tsipras to buy time by assuring markets that the loosening of austerity will be accompanied by reforms, and that any restructuring of Greece’s debt will be done in a negotiated manner.

EU officials have been in contact with members of Syriza for weeks, and Tsipras will meet his European counterparts during an EU summit on 12 February. The European Union will be willing to offer Greece lower interest rates and an extension of its debt maturities, but it is unlikely to accept a new write-down of Greece’s debt, most of which is held by the European Central Bank and eurozone governments. Countries in Northern Europe, including Germany and Finland, are under political pressure not to accept another write-down of Greece’s debt, which last occurred in 2012.

Syriza will face internal divisions because the party consists of a coalition of left-wing groups with differing views on how to manage the Greek economy and negotiate with Brussels. In the coming days, Tsipras will see debates with his new allies in the Independent Greeks as well as within his party to hammer out a negotiation strategy. Athens’ first strategy will be to seek an agreement with the European Union. But with both actors confronted by major political constraints, serious disagreements could take place in the coming weeks.

This article was originally published by Stratfor Global Intelligence on 26 January 2015. It is republished with permission.