G20: How Can it Promote Effective Development?

A fast-changing development landscape is no longer a novelty. Yet we know little about what this means for recipient country governments as they now have many more development financing options than ever before to support their national strategies in a new age of choice. But can developing country governments make the most of this larger set of financing options, or does managing greater fragmentation and complexity pose a challenge for them?

Ahead of the G20 Summit in Hangzhou and the handover of the G20 presidency to Germany, I would like to recommend three actions to G20 members, individually and as a group, and to the Development Working Group in particular. These policy recommendations are meant to increase the effectiveness of G20 members’ development assistance programs for recipient countries at a time when countries are called on to step up their efforts to implement the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the development finance landscape has become more complex.

These recommendations are grounded in the evidence gathered in a recent Overseas Deveopment Institute (ODI) project that conducted interviews with senior government officials in nine sub-Saharan African and Southeast Asian countries over the last four years. The report looked at development finance from the perspective of recipient country governments: how much assistance they actually receive from different sources and their preferences for terms and conditions.

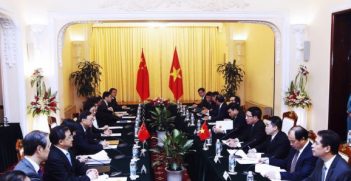

First, I recommend that some emerging donors, notably China, take a more active role in country and global level fora. When we look at all the external flows beyond traditional official assistance at the global level, the share of assistance from China and other emerging donors is small compared to other sources. Yet from the perspective of the recipient country governments we analysed, the picture appears very different. Considering the subset of external flows that governments can directly access, China provides on average 50 per cent of these flows in the case study countries and more than 70 per cent in countries such as Laos, Cambodia and Ghana. In Kenya, Chinese assistance matches that of the African Development Bank and China is also the largest bilateral lender to the Kenyan government. But despite China’s importance as a finance provider, its participation in country coordination mechanisms and global fora is often only passive or as an observer.

Second, G20 members should strive to meet developing countries’ preferences for development finance. The government officials interviewed not only wanted more finance, especially to support infrastructure development, but they wanted projects that are demand-led, that are aligned to their national priorities and, most importantly, that are delivered quickly. Some governments willingly discarded financing options with more favourable financial terms and conditions in favour of funds that that were disbursed more quickly, and even turned down projects that were implemented too slowly. The programs of G20 members—traditional and less traditional donors alike—should reflect the priorities of these developing countries in order to increase the effectiveness of development cooperation and to stay relevant in a rapidly evolving development landscape.

Third, we recommend that G20 members do not load countries with too much debt. Most countries can now access loans and some of them have recently issued bonds in the international financial markets. While international sovereign bonds are more expensive than, for example, loans from multilateral development banks, they have a number of advantages: they do not come with policy conditions, there is more discretion in the use of funds and they signal a country’s ability to access international financial markets. But several countries are now hitting their debt-to-GDP ceiling. There is a progressively more visible trade-off between taking up new loans and keeping the risk of debt distress low. So donors have to be mindful of the potential consequences on debt sustainability in order to help developing countries to avoid slipping into another debt crisis in the medium term.

There are three key action points that the G20 and its member countries can take into consideration to increase the effectiveness of their development assistance programs: China and other emerging countries should play a stronger role at the country and global levels; G20 members should strive to meet developing countries’ preferences for ownership, alignment and speed of delivery in their development cooperation programs; and, last but not least, they should be mindful of the consequences on debt sustainability when they lend to developing country governments.

Dr Annalisa Prizzon is a research fellow with the Centre for Aid and Public Expenditure at the Overseas Development Institute working on development finance issues such as aid effectiveness, debt sustainability analysis and development macroeconomics. She was an economist and policy analyst in academic institutions and international organisations such as the OECD and the World Bank Group. This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.