Fragile Geopolitics in the Himalayas

China and India remain deeply distrustful of each other’s strategic regional and geopolitical intentions. It remains to be seen whether they will continue to cooperate as pragmatic political and economic partners.

Renewed border fights between China and India in the Ladakh region have been taking place since May 2020 are a reminder of the previous military standoff along the disputed Bhutan-China border area in June, 2017. Increased militarisation in long-disputed border areas and heightened nationalism on both sides will make future border clashes likely.

2020 China-India Border Conflict in Ladakh

Since early May 2020, Indian and Chinese troops have clashed violently in the Indian-administered Eastern Ladakh region. This disputed border area was also the place where the 1962 Sino-Indian war started, and numerous skirmishes between Indian and Chinese troops stationed nearby have taken place there since. This time, India’s construction of a strategically important bridge in the Galwan Valley has led to Chinese troops incurring into Indian-claimed territory along the Line of Control zone. Chinese and Indian troops have had serious clashes intermittently since. The situation first was deescalated on the 6 June when Chinese and Indian army commanders met under the consultation mechanism for border issues established during the Modi-Xi summit in India in October 2019.

Since that meeting, however, the border situation has worsened again with the first casualties on both sides since the 1962 war. Both countries have accused the other of border transgressions and rationalised their actions through nationalism. India and China had increased their military presences along the China-Bhutan-Indian border since the 2017 Doklam clashes, making such incidents more likely and more prone to escalation.

2017 India-China standoff at the Bhutan-China border in Doklam

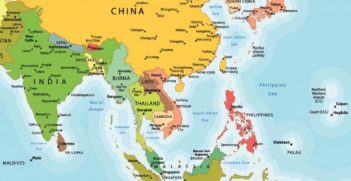

In June 2017, a ten-week-long standoff between China and India started along the 470 km long Bhutan-China border. The Doklam Plateau, which borders China and Bhutan, has been claimed by both Bhutan and China for a very long time. Bhutan has administered the area from its capital, Thimphu. China has insisted that the area has historically been an integral part of Tibet. India sent troops into the area to stop China’s road construction. Indian and Chinese soldiers clashed in minor skirmishes, the first military encounter since the 1962 Sino-India war. India had a strategic reason to intervene as full control of the Doklam Plateau would give China a vantage point over the Indian Siliguri Corridor nearby, also known as the Chicken’s Neck. This small strip of land is a strategically important corridor connecting the eight north-eastern Indian states with the rest of India.

The UN urged both sides to resolve the issue peacefully through dialogue. After more than two months of military confrontation, both India and China withdrew their soldiers to their previous positions on 28 August, 2017. However, both countries have since increased their military presence near disputed border areas.

Doklam: Bhutan in a geopolitical triangle

Bhutan signed a friendship treaty with India in 1949 which gave India the right of “guidance” in its external affairs. Bhutan has since relied on India for its security. The treaty was revised in 2007 to give Bhutan more control of its external affairs. Since 1961, India has been Bhutan’s largest development partner, so it was convenient for India to jump to Bhutan’s “defence” during the 2017 Doklam incident.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s first official state visit in June 2014 was to Bhutan. He stressed that the two countries share a “unique and special relationship.” Modi’s policy of “Neighbourhood First” sought to invigorate India’s relations with smaller regional neighbours such as Bhutan to counter China’s growing presence in the region.

Tibet and Bhutan look back to centuries of religious affiliations, as well as conflicts between Bhutanese and Tibetan rival groups. Bhutan has been wary of China’s strategic intentions and the Doklam incident didn’t help. India and Bhutan have not joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), unlike other South Asian countries. Though China tried to mend fences with Bhutan, the bilateral border negotiations over the Doklam Plateau have not resumed. It can be assumed that China, so far, has not given up its territorial claim to the Doklam area.

India and China strategies: Doklam and beyond

China is India’s biggest trading partner. Because of low levels of Indian exports to China, India hoped that China would lower tariff barriers for Indian exports. Recent years also saw a considerable increase in foreign direct investment into India by Chinese private and state-owned companies.

India had also garnered international support during the standoff. The BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) leaders’ summit in Xiamen, China in October 2017 offered an opportunity to save face and calm things down. The subsequent bilateral meeting between Xi Jinping and Modi in 2018 in Wuhan, China, created the concept of “Wuhan spirit.” Economic cooperation in third countries and cooperation against terrorism were the focus. Both leaders wanted bilateral relations to return to a more normal footing. They agreed, at their second bilateral summit in Mamallapuram, India in October 2019, on closer military and trade ties.

India also increased its geopolitical flexibility. In 2017 and 2018, the decade-old concept of security cooperation between the United States, Australia, India, and Japan ─ the “Quad” ─ was revitalised. In 2018, India and the US signed a defence pact and, in early 2020, India purchased US defence equipment.

India continues to be deeply worried about China’s BRI activities in South Asia. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is seen by India as a major security threat. It is a part of the BRI, costing US$46 billion, and runs through the Pakistan-controlled Assad Kashmir, a territory claimed by India. As one answer, Modi in 2015 announced the Security and Growth for All in the Region policy. This policy focuses on maritime cooperation with Indian Ocean neighbours and improving regional connectivity through infrastructure projects including roads and waterways to Bhutan and Nepal.

China’s strategic intention for starting the Doklam standoff are less clear. They may have wanted to drive a wedge between India and Bhutan or to underline their sovereignty over Tibet. China may also have wanted to avoid driving India closer to the US, especially considering the US’s revival of the Quad. Political cooperation with India within the BRICS framework and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) remains important for China, as India and China have often taken similar stands on a range of topics. The 2017 BRICS summit helped smooth bilateral relations after Doklam. In any case, the Doklam conflict ended with a peaceful disengagement of both armed forces.

Conclusion

Unresolved border questions between China, India, and Bhutan are likely to flare up again, especially with increased militarisation along the border and heightened nationalism on both sides. Unless Beijing and New Delhi achieve a durable modus vivendi on their own borders, they cannot expect their other diplomatic manoeuvres to have a lasting effect on the geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific region.

It is still an open question whether the previous China-India partnership of convenience on trade and investment issues and in multilateral organisations, such as BRICS and SCO, will continue. India remains seriously concerned about a more assertive China and its increased role in the region. India, therefore, aims to have greater geopolitical flexibility by reinforcing its ties with its immediate South Asian neighbours and with its Quad partners.

Dr Anne-Marie Schleich was a career German diplomat from 1979 to 2016. Most recently, she was the German Ambassador to New Zealand and seven Pacific Island Countries from 2012 to 2016. She was the German Consul-General in Melbourne, Australia from 2008 to 2012 and has also served in Singapore, Bangkok, Islamabad and London. This is an edited version of an article that was also published in Denkwuerdigkeiten, Journal der Politisch-Militaerischen Gesellschaft, Nr. 118, June 2020.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.