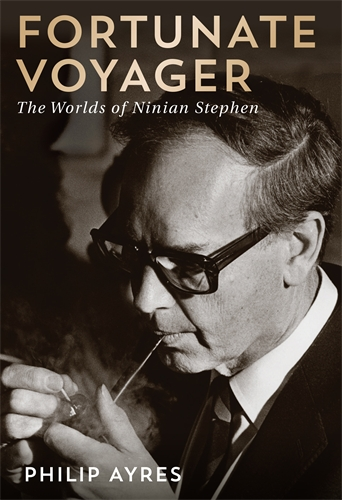

Fortunate Voyager: The Worlds of Ninian Stephen

In February 1983 the Prime Minister, Malcolm Fraser, fretted over speculation that Bob Hawke was about to topple Bill Hayden and assume the leadership of the Opposition. Attempting to dictate events rather than be dictated to by them, Fraser called a press conference for 1.00 pm at which he intended to announce an election. He then travelled, unannounced, to Yarralumla to secure a double dissolution, which was surely a formality given that the necessary constitutional conditions existed. However the Governor-General did not see it that way. The constitutional conditions for a double dissolution election had existed for months; why did Fraser believe that an election was so urgent now? In His Excellency’s view the 40 pages of explanation provided by the Prime Minister required careful consideration and in any case, the Polish Ambassador was expected for lunch. By 4.55 pm, the Governor-General had considered and acceded to Fraser’s request. The election was called. However, by this time the popular Hawke had ousted Hayden. The rest is history.

This coolness is indicative of the man as revealed to us in Philip Ayres’s Fortunate Voyager: The Worlds of Ninian Stephen. Ayres describes a man who was ‘relaxed and nonchalant’ and above all ‘fortunate’. Fortunate indeed, as he excelled in multiple careers. Reading Ayres’s excellent biography causes one to realise that although we know Stephen well – as a Governor-General and as jurist – there is much we do not know, much that was formative in the development of the man.

The world in which Stephen was raised was about as removed from 1930s Australia as it could have been, for the young Ninian grew up on the ski runs above Montreux and under the sun of the Cote D’Azur. In this distinctly cosmopolitan world, Stephen enjoyed the patronage of his mother’s employer (and his own namesake) Nina Mylne. Mylne, a woman of independent views as well independent means, encouraged Stephen in his scholastic development. He was a witness to history, attending the 1938 Nuremberg rally. Stephen’s upbringing was in many ways unorthodox for the time. He himself described the relationship between his mother and Nina Mylne as ‘complicated.’ Ayres handles such matters deftly.

Those of a legal bent will no doubt enjoy reading Ayres’s account of Stephen’s career as a jurist. The logic of various judgments is dissected forensically, but remains engaging to the layperson. In other areas Stephen remains elusive, even to his biographer. His views on politics and ultimate position on issues such as the Whitlam dismissal are cases in point.

No less interesting is the world of diplomacy which Stephen first entered as Governor-General by expanding that role to include international visits and then later embarked on a new career as a mediator that included work on disputes ranging from Northern Ireland to Burma.

Ayres’s contention, that Stephen was a cool individual rather than a driven one, and his framework of studying the various worlds which Stephen voyaged through, shows his talent as a biographer. Ayres clearly admires his subject; however, he maintains his objectivity. Ayres was no doubt aided by the fact that Stephen is a diligent archivist, keeping copies of both his incoming and outgoing correspondence. In Fortunate Voyager, Ayres reveals the unknown Stephen. It is a story that deserves a wide audience.

Philip Ayres, Fortunate Voyager: The Worlds of Ninian Stephen, Miegunyah Press, 2013

Reviewed by Cameron Hawker, President, AIIA ACT Branch