Taming Foreign Influence in Australia

Australia’s historic relative isolation has failed to protect it from the ambitions of foreign influencers. After the most recent scandal involving alleged clandestine interference, what lessons can Australia learn from its past?

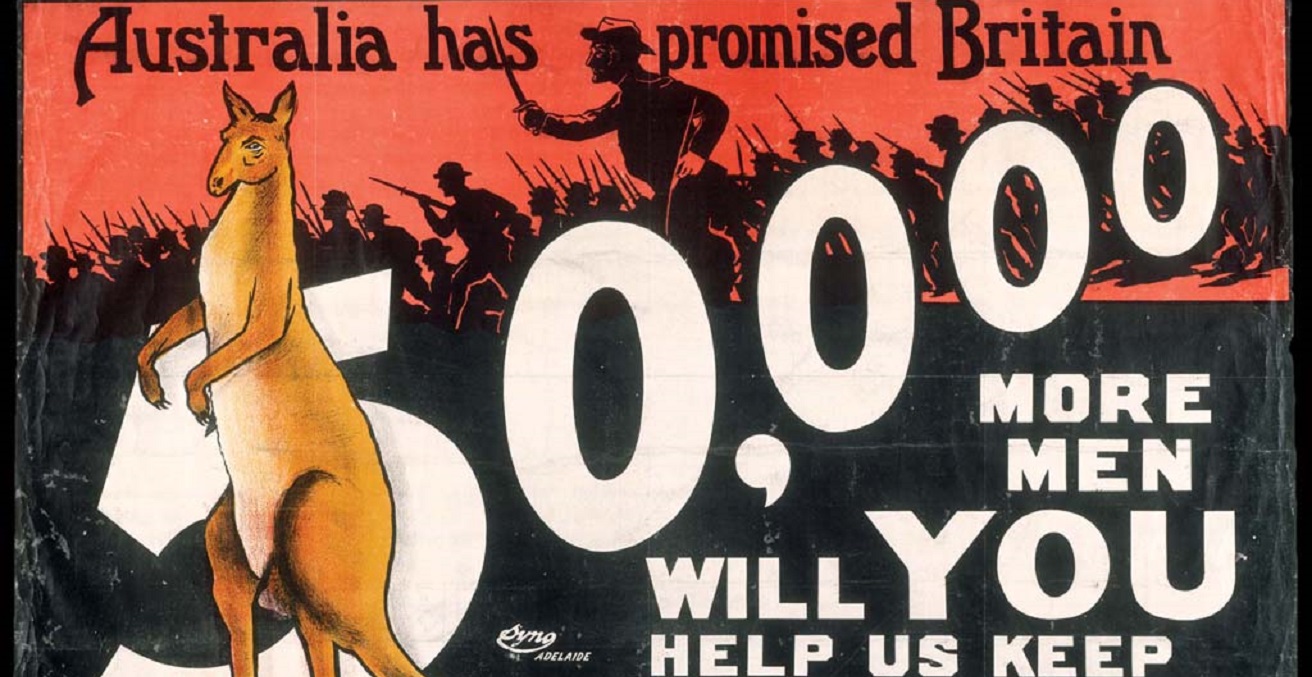

The news of the Turnbull government’s moves to ban foreign political donations and establish a public register for people who seek to influence the Australian political process on behalf of foreign interests comes in the wake of the Sam Dastyari scandal. However, Dastyari is no Robinson Crusoe. Both major parties have a history of being courted by foreign influences. Indeed, as a colony, Australia outsourced its entire foreign policy to London. As recently as 1935, Australian foreign relations were conducted by the British Empire.

The great schism of 1955 that split the Australian Labor Party (ALP) and ensured it stayed in the opposition wilderness for almost two decades was a direct result of Soviet influences in the party and Australian society in general, despite party leader Doc Evatt believing otherwise. More recently, former Minister for Foreign Affairs and current Director of the Australia-China Relations Institute (ACRI) Bob Carr highlighted the influence wielded by the pro-Israel lobby in Melbourne and former Minister for Defence Joel Fitzgibbon was criticised for his friendship with the Chinese Communist Party-linked Helen Liu.

The ALP does not have a monopoly on being susceptible to foreign influence. Richard Bullivant, a former intelligence officer at the Office of National Assessments (ONA), detailed how defector Chen Yonglin claimed that, among other pro-Chinese actions during the Howard government years, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade assisted the Chinese government in a lawsuit lodged in the New South Wales Supreme Court by an Australian citizen against a Chinese secret police organisation. More recently, former Minister for Trade Andrew Robb has been scrutinised for some of the decisions he made while in government, given how he quickly became a lobbyist for a Chinese Communist Party-connected business.

Moreover, it has been revealed that despite ASIO warnings, both major parties have accepted millions of dollars in donations from Chinese Communist Party-linked entities, including from the billionaire at the centre of the Dastyari scandal (and financial backer of ACRI), Huang Xiangmo. And there is always the looming shadow of the United States in Australia’s political system, as the symbiotic relationship grows ever deeper.

But why is all of this important? To the person on the street, the idea that the Australian government, elected by the Australian people to manage Australia’s interests is using the time, money and resources available to it to promote the interests of another state goes against the concept of national sovereignty and undermines the public’s confidence in democracy.

However, it is more subtle than that. Donations to political parties in Australia, as in other Western democracies purchase political access for donors. Large contributors can demand one-on-one meetings with ministers at relatively short notice. Smaller contributions often grant donors the chance to mingle with politicians at dinners or receptions, or attend a privileged advanced presentation of upcoming policy initiatives. Both donors and politicians deny that donors receive decisions or influence in return for cash. Instead, they merely receive an opportunity to state their case to decision makers. Foreign powers can use this access in order to try and shape the government’s interpretation of, and responses to, international circumstances, as well as contribute to the definition of the national interest.

As the Asia-Pacific region increasingly becomes the centre of global geopolitics, Australia’s position as a middle power makes it an important player in the new Great Game. At the moment Australia is, as it has been for the last several decades, firmly in the US camp. However, China is apparently playing a long game, using its economic power in a carrot and stick type of leverage throughout the region as well as using traditional Cold War espionage tactics with 21st century technology.

As far back as 2003, China aimed to make Australia a second France, so it dared to say ‘no’ to the United States. Specifically, China attempted to get Australia to declare it wouldn’t participate in any conflict with Taiwan, one of the most likely sources of military clashes between China and the US, and China’s number one foreign policy objective.

ASIO’s warnings and Turnbull’s reforms are a line in the sand. They are are a direct message to the Chinese that the rules of the game have changed, as removing the financial incentives of the main parties to grant access to foreign donors and increased public scrutiny makes it harder for China to continue with business as usual. Publicly, China has responded in its usual flamboyant fashion, though the situation would no doubt be seen differently if the shoe was on the other foot, and Australian interests were caught meddling in China’s internal affairs. It remains to be seen if China will take more serious action. The ball is now in its court.

Stjepan Bosnjak is studying a Master of Arts (Research) at Victoria University.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.