Fight with Intelligence: Information Sharing and the Absence of Trust

Members of the Indian Ocean Rim Association have declared the need to counter transnational terrorism through the sharing of intelligence. The absence of trust is one of several obstacles that remain for integrated impartial intelligence.

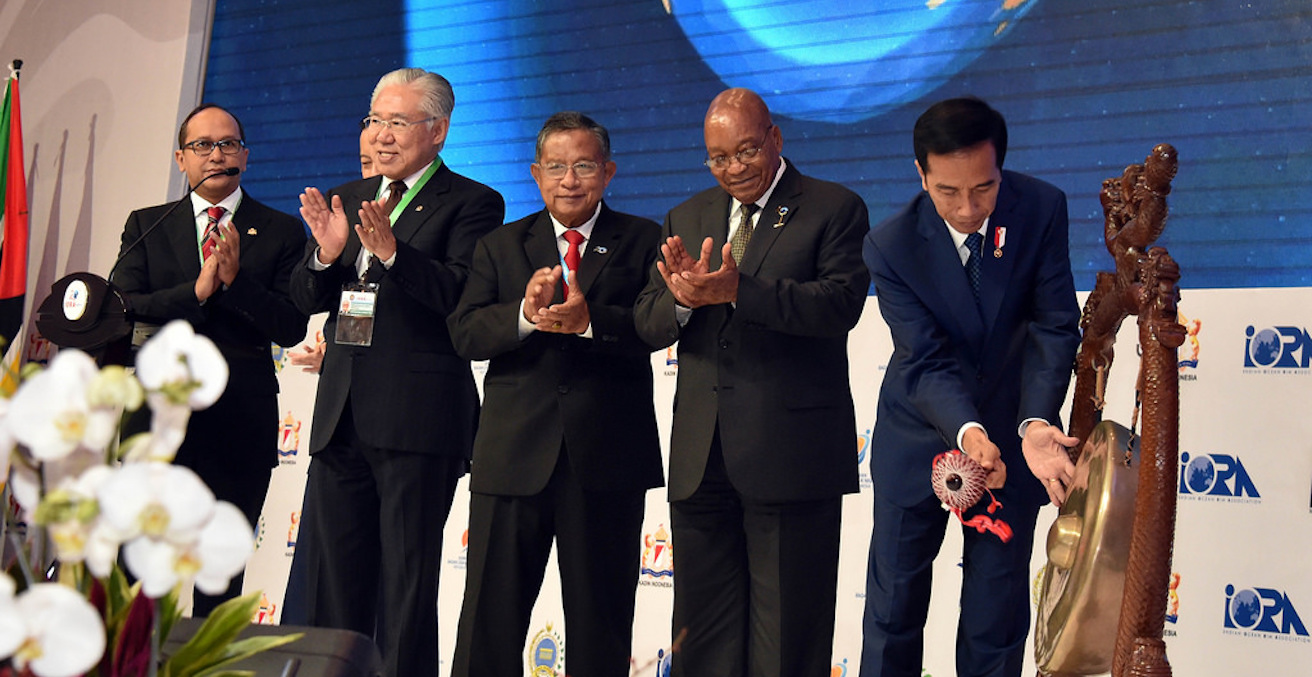

In March last year, member states of the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) declared the need for cooperation to counter transnational terrorism, share intelligence and information and strengthen national and regional institutions. The overall aim is to support better-informed risk analysis and risk mitigation in order to prevent and stop terrorism. As the range of threats grow more complex, Australia’s resources, capabilities and methods of security operation must all be evaluated on a recurring basis. By integrating and sharing impartial intelligence, countries are able to understand the regional and international environment better and can be warned of looming threats to national interests.

Both the Indian Ocean region and the notion of ‘decision advantage’ based on the careful utilisation of intelligence are receiving increased attention in recent years. One of the emergent challenges states face in the region is how to manage and deal with non-traditional security threats. Climate change, illegal fishing, piracy, drug smuggling and arms trafficking all pose a security threat to littoral states and extra-regional states. A drive for greater all-source intelligence information ‘fusion’ will demand both people and systems to increase communication and coordination across similar issues, alter bureaucratic relationships and adapt to technology trends.

Obstacles for intelligence cooperation in the Indian Ocean region

One issue in particular that has consistently garnered the attention of Indian Ocean region states is extremism and transnational terrorism. However, cooperating to counter transnational terrorism through joint action is easier said than done.

There are several factors that pose significant challenges to the systematic pooling of resources and cohesive intelligence cooperation in the region.

Firstly, unlike South East Asia or Europe, the Indian Ocean region does not have a multilateral institutionalised security governance framework in place to coordinate state action and prioritise security threats. In South East Asia, security governance practices are largely shaped by the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) that helps to design, facilitate and encourage cooperation on regional security issues such as terrorism and extremism, transnational crime, maritime law enforcement and disaster relief. The region has no such organisation except for the IORA, which has widely been considered ineffective and sluggish in bringing about critical collective security reforms in the region. IORA currently remains poorly placed to ensure the sharing of information on a consistent, effectual and time-imperative cross-agency basis.

Secondly, there is no unified identity within the Indian Ocean region, as it encompasses states in East Africa, the Middle East, South and East Asia and Australia. The shift in rhetoric towards the notion of the Indo-Pacific arguably only crystallised in 2011 or 2012: it remains to be seen if the new definition will become entrenched. A lack of a strong identity, at least in the short term, will continue to complicate the search for a consensus-based alignment directing overarching goals, expectations and objectives for information sharing. Additionally, a number of states, including India, have been exposed for a lack of unity, coordination and progress within their own multiple domestic intelligence agencies (which also contain a domestic counterterrorism mandate). The existence of turf wars and inter-agency rivalries have often combined to make effective counterintelligence pathways all but impossible.

Thirdly, the geopolitical tensions in the region have generated feelings of mistrust between states. The establishment of a trust environment is absolutely necessary to move towards greater information sharing. This lack of trust – compounded by security sectors characterised by secrecy, dissimilar legal frameworks and divergent ‘rules-of-the-road’ for how and when intelligence can be shared – increases complexity at both operational and strategic levels. For instance, where there are concerns that a partner might be unreliable and compromise the protection of sources and methods, states will tend to forgo the risk of forming a working intelligence relationship. Sharing information is ultimately a balance of interests. Mission effectiveness will always be predicated on the careful assessment and management of the risks associated with it.

Finally – unlike in the Five Eyes arrangement between Australia, the US, UK, New Zealand and Canada – many states in the Indian Ocean region do not have a long history of working with one another to solve common problems. The desire to prevent, pre-empt and disrupt future terror attacks has sparked a shift by many intelligence agencies, including those in Australia, toward establishing case-by-case partnerships or memoranda of understandings (MOUs) with non-traditional allies. In 2015, Australia and Iran made an informal agreement to share intelligence related to extremist groups in Iraq. However, a major concern with such intelligence liaison relationships is that many of these new partners, such as Iran, have poor human rights records.

The formal position of the Australian intelligence community is that it does not use torture, nor does it sanction or condone torture used by other states. But despite the fact Australia has ratified the UN Convention against Torture, at present there are no cohesive guidelines that can influence state practices to better facilitate information sharing practices and stop torture in informal intelligence partnerships. There is an extensive, but arguably only skin-deep and expedient, regional framework for safeguards and expectations about appropriate risks and behaviour.

All these above external factors pose open-ended barriers and challenges to generating and sustaining state cooperation in the Indian Ocean region to effectively tackle issues like transnational terrorism, piracy, drug trafficking and illegal fishing.

Certainly Australia along with other like-minded nations, must be able to meet the threats to national security interests by drawing the most balanced, informed conclusion possible from the intelligence collected, analysed and disseminated. Yet there remain many different dimensions to the intelligence-sharing puzzle. Despite a wide-ranging political appetite to strengthen intelligence sharing to better inform policy-makers, the elements of policy, structure and process must all be successfully interwoven to build trusted information flows with appropriate checks and balances while meeting country-specific intelligence standards and goals.

Dr Daniel Baldino is a senior lecturer and discipline head of the Politics and International Relations program at the University of Notre Dame. He is currently the Western Australian chapter convener for Australian Institute for Professional Intelligence Officers (AIPIO).

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and can be republished with attribution.