Europe is Well Equipped for Challenge and Change

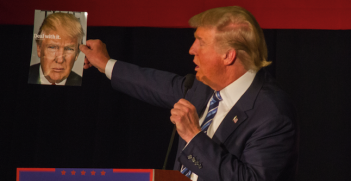

In a time of global turmoil and in the lead-up to European Parliamentary elections in May, the EU is facing serious political and security challenges. These include immigration, a new “populist” coalition government in Italy, uncertainty in Germany, Brexit negotiations, Donald Trump’s disturbing initiatives and Russia’s strategy of intervention and subversion.

The argument I wish to defend is that the European Union has the capacity and political will to resist negative trends, and should play a more significant role in Western security. My definition of the West is global and includes all democratic allies from Europe to North America, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan.

Collective is strong

Contrary to “politically correct” opinions, multilateral institutions may prove more resilient and more strategic than the Member States that compose them. The EU is not only the aggregate of 28 nations, but also a collective body. And this 500-million-person political, economic and judicial organisation is the richest economic region in the world. Most EU countries belong to NATO, the most sophisticated political and military alliance ever created. A number of neighbours are closely integrated in the EU space, like Switzerland and Norway, or are members of the Atlantic Alliance, like Norway and Turkey.

From its very inception in the 1950s, the European Community has promoted a supranational system, respectful of national diversities. It has always kept doors open to new members. Because of their dedication to peace and security, European nations pay close attention to neighbouring countries. They have adopted strategic plans toward the Eastern partnership countries and Mediterranean neighbours. The EU remains a very attractive prospect in Tunisia, the Balkans, Eastern Europe, Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova.

The EU’s strength and attractiveness is based on its common public policies, institutional capacity (including European law and court), and commitment to peace, rule of law and economic development in respect of social justice and human security.

The EU’s principles and values, as well as actual practice and forward-looking strategy, have given force and adaptability to the collective institution. What many denounce as Europe’s flaws have proven to be its deep resource, including its immunity to hare-brained decisions: a consensus method that calls for intense discussion – even to breaking point such as with the Greek crisis – and its commitment to compromise accepted by all. When a policy is approved, EU institutions can exert pressure on Member States to see the decision implemented. Common policies can result in a cumbersome process, and tactical failures, but, as it is essential to reach a consensus, each party makes concessions. Consensus building is a modern, effective form of power.

The force of the multilateral process resides in its very collectiveness. The common decision belongs to the supranational institution, not to national states and governments. For instance, after the annexation of Crimea and intervention in Eastern Ukraine, the EU easily came to the decision to impose sanctions against targeted Russian individuals and organisations. The 28 have maintained, and re-voted, these sanctions several times since 2014. Even Viktor Orbán would not go for Hungary’s veto, because of the political cost of being against all.

Regional and global security challenges

The European Union was created with the explicit goal of promoting peace, solidarity and common prosperity. It is now becoming an effective international actor in the fields of climate change, energy security, information security and social justice, in particular the struggle against inequalities.

Europeans want a world that is not driven by conflicts. As they cannot insulate themselves in a space of their own (a temptation for the English and the Americans), the peaceful resolution of disputes is the only reasonable option. Belonging to a wider space, beyond national boundaries, is a reality that cannot be reversed.

What Donald Trump can do – when Congress, courts and citizens do not stop him – cannot be done by a European far right, or “illiberal” leader precisely because they are constrained by EU obligations and legislation. To re-erect walls and trade barriers, short of a full exit from the EU, is very difficult to envisage. The immigration crisis of 2015-16 was a big test, where a few governments broke the solidarity consensus andclosed their borders. Eventually, the EU came to an unsatisfactory out-of-crisis solution, but overcame the institutional deadlock.

Brexit remains an exception. Demagogues in Italy, Hungary and Poland, will not take the risk. They cry out a nationalist, xenophobic discourse, and impose regressive policies at home, but lack the political or economic resources to cut their country off from the European market. Brexit is harming the UK much more than it is harming the EU.

In Europe, values are a guide for common policies, and coordinated action. But democratic values are not a toolbox, and do not provide us with guidelines and instruments in negotiating with Russia, or any other non-democratic government. Such regimes openly reject the principles we deem “universal” and defy our conception and practice of rule-of-law government. Gone are the days of trustful cooperation with Russia, in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The conflict in Eastern Ukraine, and more dramatically the devastating war in Syria, together with the unprecedented migrations of refugees from Syria, Iraq, Libya and Afghanistan, have changed Europeans’ perceptions and policies. The security challenges we face today are very significant. We can no longer pretend that Russia plays the role of honest broker, or that the USA under Trump will be up to its responsibilities and commitments as the leading economic and military power.

The EU can take on a bigger and broader international role, and wield more influence, by deconstructing old blueprints and taking the lead in a number of key issues, notably ecology and human security. Currently, there is a window of opportunity to engage in innovating thinking, make propositions, and take initiatives with trusted partners, from Australia to Japan, Canada, and beyond.

Dr Marie Mendras is Professor at Sciences Po’s Paris School of International Affairs, and Research Fellow with the National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) in Paris.

This article was originally published in The EU and Australia: Towards a New Era, the official publication of the EU-Australia Leadership Forum 2018, which took place from 18-22 November. It is republished with permission.

The AIIA is part of the international consortium selected to deliver the EU-Australia Leadership Forum project, a three-year initiative funded by the EU. Click here for video highlights of the forum.