Elections to Be Held in Post-Coup Zimbabwe

On 30 July, Zimbabweans head to the polls. The volatile situation highlights the need to stop idealising opposition political parties while remaining critical of incumbent governments.

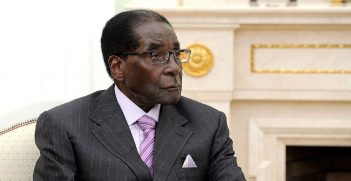

In the aftermath of the November 2017 soft military coup that resulted in the resignation of Zimbabwe’s 37-year-long president, Robert Mugabe, Zimbabweans are headed to the polls on 30 July. The polls come in the aftermath of the post-coup Mnangagwa government’s unwillingness to form a Government of National Unity with the country’s opposition political parties. Tensions and hopes are high as the country’s post-coup transition continues.

Militarised politics

Zimbabwe’s harmonised presidential, parliamentary and local government elections taking place in a more open political environment, which has seen opposition political parties able to campaign without impediments throughout the country. While the credibility of the Zimbabwean Electoral Commission is still being questioned, international observers from across the world have been granted permission to observe the elections. This has not been the case in previous elections. The harmonised elections come amidst reassurances by the incumbent Mnangagwa government that they will be free, fair and credible. Some analysts question these reassurances given pro-ZANU-PF military involvement in previous elections.

However, the Zimbabwean political landscape has shifted since the November coup. Opposition political parties supported the military coup and organised a civil society march on 18 November 2017 that helped Mnangagwa’s faction within the incumbent ZANU-PF party consolidate its hold on power. The military coup saw opposition support for active military involvement in the country’s politics which, arguably, increased Zimbabweans’ trust in the military. Such support for the military coup shows that when it comes to Zimbabwean politics, there is no distinction to be made between civilian and military politics.

Post-coup, the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) Alliance, has pledged to protect the “rights and interests” of liberation war veterans. MDC Alliance leader, Nelson Chamisa, recently applauded the military for pledging neutrality in the upcoming elections. The MDC Alliance is actively courting the military and reclaiming the anti-colonial liberation war narrative. This is the narrative on which the country was built and it has been reclaimed in anticipation of an electoral victory following the July 30 harmonised elections. However, despite such efforts, it remains to be seen whether the Zimbabwean military, deeply intertwined with the incumbent ZANU-PF party as it is, will continue to observe its self-proclaimed neutrality.

Other issues and potential outcomes

Both Mnangagwa and Chamisa are campaigning on a common platform of economic renewal and job creation, with significant overlap in both presidential candidates’ messaging. The contest is, therefore, less about the issues than about the personalities involved and how well each manages to present themselves and their party as a more desirable option. This is notable given in a recent survey conducted by Afrobarometer (an independent Pan-African research network), 40 per cent of Zimbabweans are reported as indicating that they would vote for the incumbent ZANU-PF, while 37 per cent indicated they would vote for the MDC (both the party and the MDC Alliance). The race is close.

Moreover, 86 per cent of Zimbabweans surveyed reported that they would definitely be voting, with only 28 per cent expressing the fear that people in high places will find out which way they voted. In terms of support for the two main parties (incumbent ZANU-PF and MDC Alliance), 34 per cent of surveyed individuals indicated support for ZANU-PF, while 29 per cent indicated support for the MDC Alliance. Only 1 per cent supported another party, with 36 per cent refusing to disclose their party preference.

This once again demonstrates the closeness of the race. Indeed, on the issue of job creation, 42 per cent of those surveyed believe MDC Alliance’s Chamisa would be better placed to create jobs, while only 32 per cent believe ZANU-PF’s Mnangagwa would be able to do the same.

The MDC Alliance continues to command greater support in urban areas, whilst ZANU-PF continues to command greater support in its tradition rural strongholds. However, undecided voters will by and large decide the presidential race. These survey findings have reinvigorated a previously beleaguered opposition. However, in a country where any non-opposition victory is regarded with suspicion, and in a Southern African regional context where opposition political parties threaten civil war when elections fail to yield desired results, the elections could be result in an unprecedented level of instability.

Indeed, Zimbabwe’s MDC Alliance has been referred to as the country’s Renamo, the party that re-ignited Mozambique’s civil war, following contested municipal election results in 2013. Zimbabwe’s MDC has similarly been threatening civil war since 2016. Zimbabwe’s elections could, therefore, potentially result in protracted conflict if both the incumbent ZANU-PF and opposition political parties fail to observe the Peace Pledge signed by various political parties last month and in early July.

The Peace Pledge was signed in the aftermath of an explosive blast at a rally in Bulawayo where President Mnangagwa was present. The blast went off close to the president as he was leaving the stage following a speech to supporters on the campaign trail. Several people were injured and the president has subsequently claimed that the New Patriotic Front (NPF), a new party with links to former president Robert Mugabe and his wife Grace, was responsible. The NPF is also known to work with the MDC Alliance, while the latter often refers to itself as the ‘Red Army’. Despite the Peace Pledge, an opposition loss in light of these developments is likely to ignite increasing violent outbursts from Zimbabwean opposition political parties.

The way forward

Zimbabwe’s ongoing post-coup transition and volatile situation highlight the need to stop idealising opposition political parties while remaining critical of incumbent governments. Moreover, the situation highlights that liberal institutions, by virtue of their competitive logic, are ill-suited to an African context grappling with intra-state conflicts. A post-election Government of National Unity may be the way to go in order to ensure not only stability but collaborative rather than competitive democratic governance in the country. Some analysts have suggested that this is a likely outcome; however, it remains to be seen whether the relative stability the country is currently enjoying will be sustained in the post-election period.

Tinashe Jakwa is a doctoral researcher at the University of Western Australia. She is studying how liberal institutions and norms increase state instability in Africa.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.