Don’t Look Away From Aylan Kurdi’s Image

Last week, an image of a drowned refugee child became an icon before our eyes.

Of all the photographs of this crisis, why did this one finally allow us to truly see these human refugees in the deluge of images that surround us every day?

The photograph that made the front pages worldwide could not be simpler. A man in uniform stands slightly hunched as if he cannot bear to raise his head. We feel his shame. In his arms is a small child. So utterly still is the child, held horizontally, that we know at once that he is dead. His arms are unnaturally straight, and we realize the body is in rigor mortis.

The photograph has the sharp focus, depth of field, wide angle and saturated color that says “news.” It was taken by Nilufer Demir of Dogan News Agency, after she made sure that there was nothing that could be done for the child. Demir felt she had a responsibility to make sure the “silent scream” of the body was heard through her images.

We see unbearable loneliness. It sears its way into our memory, instantly unforgettable.

The world now knows that the child was three-year-old Aylan Kurdi, a refugee from Kobane in Syria. This town has been heroically defended by its Kurdish residents against ceaseless attacks from the terrorist group ISIS. Photographs of the town look like European cities after World War II. Nothing but rubble.

We can open our eyes to this photograph because it reminds us of images we know well. Such iconic images carry the power of the sacred. The posture of the policeman, Sergeant Metmet Ciplak, who carries Aylan’s body, unconsciously echoes one of the key icons of Western art.

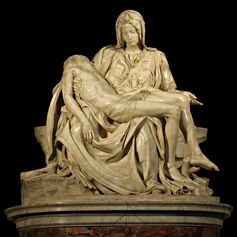

Echoes other icons

Known as the Pietà, meaning “pity,” this frequently explored motif depicts the Virgin Mary holding the body of Jesus, after he was taken down from the Cross. Perhaps the best known example is Michelangelo’s 1499 sculpture in St. Peter’s.

That unconscious recognition, regardless of our religious beliefs, allows the photograph to get past the deflecting shell that we have all developed in today’s image-dominated world. This shell allows us to survive both the constant stream of ads and the endless depictions of suffering.

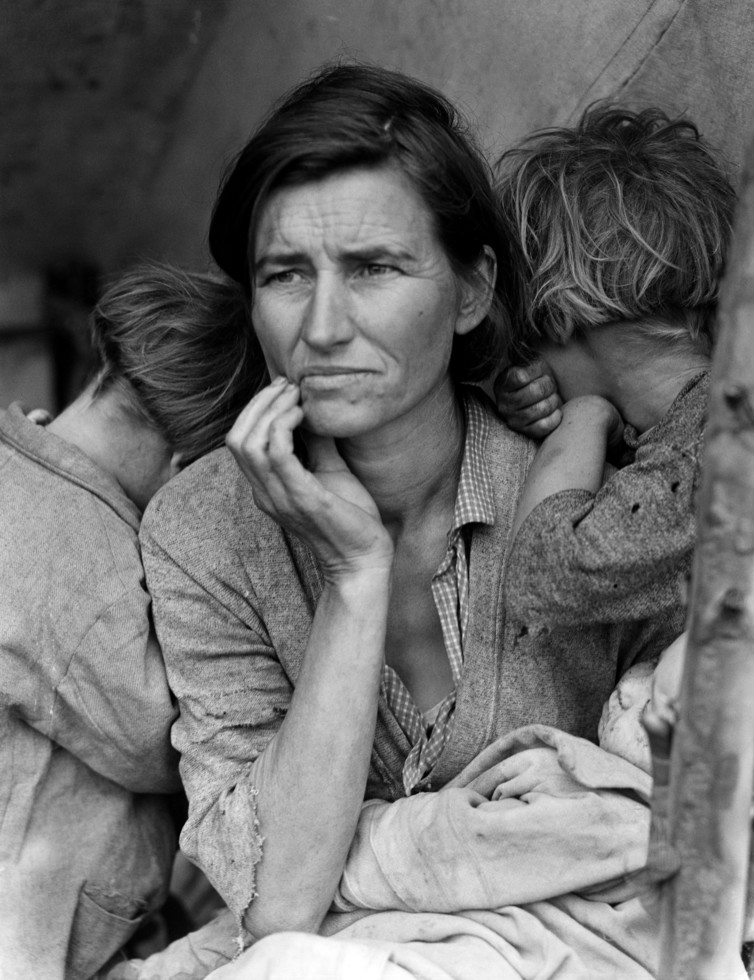

Once seen, the photograph calls to mind other such sacred moments.

Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother (1936) shows migrant farm laborer Florence Owen Thompson and her children in California. Evoking the Holy Family on the flight into Egypt, this photograph has come to symbolize the Great Depression.

No history of the Vietnam War is complete without Nick Ut’s 1972 Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph “The Terror of War.” The photograph shows Kim Phuc, a nine-year-old Vietnamese girl, running down the road naked because she had torn off her burning clothes after a napalm attack. The title is almost unnecessary, so stark is the image.

Not so well remembered today is that news organizations debated whether to print “The Terror of War” because of the young girl’s nudity. Similar debates, seen and unseen, have coursed around the picture of Aylan Kurdi and other drowned refugees.

Off and on Facebook

A similar but invisible debate over refugee images has just happened on Facebook. On August 29, anonymous pictures of drowned refugees on the coast of Libya were posted by the Syrian artist Khaled Barakeh. He called the album of these seven photographs of drowned refugee children “Multicultural Graveyard.” It has been shared over 130,000 times.

One of the images from ‘Multicultural Graveyard.’ Photo Credit: Facebook (Khaled Barakeh) Creative Commons

The album disappeared from Barakeh’s Facebook wall on August 31. Most, but not all, of the shares also were deleted. No explanation was offered to any user. When Barakeh objected to Facebook, his album was restored, at first without its title, about a day later.

Did Facebook’s mysterious algorithm delete them by accident? Or does Mark Zuckerberg employ Filipino tech drones to delete offensive content for US$300 a month, as Wired reporter Adrien Chen has suggested?

With nearly one billion users, Facebook is not just any website. It is the public square for the digital era. Who decides what should be seen there and why matters. And we saw why just a few days later.

The power of looking

When the pictures of Aylan followed, they had the authority of the Reuters news agency and were not deleted. Most commenters on social media, on blogs and in newspaper articles supported showing them. A vocal minority was against it, mostly in online comments.

Some viewers suggested the photograph might traumatize viewers. Most media outlets posted a warning regarding the “graphic” nature of the image. In fact, nothing violent can be seen. Even in the terrible picture of Aylan Kurdi lying on the beach, less often reproduced, the boy is fully clothed and no injury can be seen. Perhaps his very wholeness is what is so upsetting.

Others alluded to cultural sensitivities in non-Western societies. Certainly there are cultures where the sight of the dead is taboo. In this case, Abdullah Kurdi, Aylan’s father was quite clear: “We want the whole world to see this.”

Sixty years ago this same week, a young African-American man named Emmett Till was murdered and thrown into the Mississippi River for allegedly whistling at a white woman. His mother Mamie Till Mobley also wanted the world to see. She displayed his broken body in an open casket. Only Jet magazine and the Chicago Defender newspaper, both targeting African American audiences, dared print the photographs.

Today, she is credited with inspiring the Civil Rights Movement.

If that parallel holds, this photograph of Aylan Kurdi may also be seen someday as the beginning of a new political reality.

The alternative was foreshadowed by Marine Le Pen, leader of the French extreme-right National Front. In a speech given less than a week after it was taken, she described the photograph as a “sinister project” of what she termed the “Washington-Berlin” axis.

An estimated 2,643 people drowned in the Mediterranean before Aylan Kurdi, his brother and his mother this year. The best memorial for him would be for us to keep looking at his picture until the world sees refugees, simply, as people.

Professor of Media, Culture and Communication at New York University. This article was originally published in The Conversation on 9 September 2015. It is republished with permission.