Domestic Violence in Papua New Guinea

Although Papua New Guinea (PNG) has made much progress towards resolving issues of domestic violence, more needs to be done.

On my first posting to PNG working for the Australian government’s aid program almost 20 years ago, I visited the Daru Hospital in Western Province.

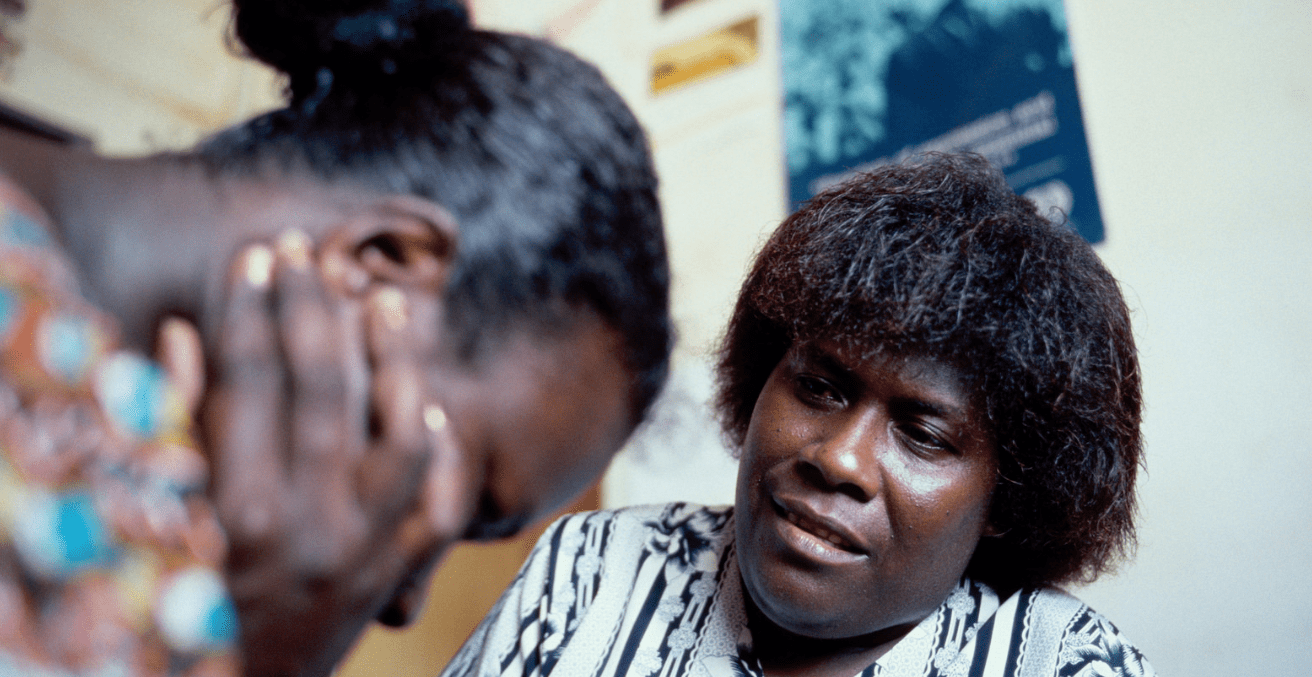

In an isolated corner of the maternity ward sat a woman with a black eye, broken hand and a few missing teeth who was breastfeeding her 12-month-old baby. Her child’s hand was in a cast and there was a large gash on her small face. The woman told me she had come to the ward because it was the only place she felt safe. She said if she returned home her husband would kill her and her baby would suffer. She pleaded for help. I tried everything I could think of but there were no local services in Daru for women escaping violent partners.

The plight of this young mother haunted me, and even though I could not do anything for her, I wanted to help others. I soon discovered that it was hard to raise the sensitive issue of family and sexual violence even though it affected most women and many men in PNG. At the time, there were also only a few civil society organisations providing support services or advocating for change.

Fast forward to today and while there are still very enormous challenges for those experiencing family and sexual violence, conditions have improved. Talking about it is much easier. And importantly it is not a donor driven conversation. The police commissioner, the commander of the PNG Defence Force, the governor of National Capital District, PNG private sector leaders, as well as leaders in civil society, the PNG public service and many others have stepped up to say, “enough is enough.” They want a different life for their families and communities.

These actions have led to new laws being passed, policies developed, training delivered, support services being established, as well as coordinated prevention and advocacy efforts. Again, many of these, while funded by donors, are led by Papua New Guineans who want change. We can learn a great deal by understanding what galvanised the transformation over the last two decades.

First, the change is directly linked to the collective efforts by many different stakeholders, all of whom had a reason to be involved. The PNG government recognised it must address this violence to progress overall social and economic development. Donors prioritised women’s empowerment in their aid programs and civil society demanded better services for the most vulnerable. More recently the private sector has become a new player recognising the significant cost to business of staff not coming to or engaging at work. New and innovative public, private and civil society partnerships such as Bel isi PNG (peaceful PNG) have emerged which demonstrate that change can happen by leveraging collective interest.

The growth of PNG’s civil society has also been of critical importance. When looking for ways to help the young mother in Daru, I I was unable to refer her to a support service. Today, at least in Port Moresby, there are several different locally run safe houses, case management centres, advocacy and coordination groups, sports bodies and other prevention focused organisations that are playing an essential role in addressing family and sexual violence. While many improvements are still necessary, including better quality and coordination of services, as well as more involvement from men, progress has been made.

It is also important to remember that every society across the world has been forced to address family violence and violence. Most, including Australia, are still on that journey. And every country has had to tread the same path of consistent advocacy for changing attitudes, making sure services exist for people who seek help, developing policies and changing laws. Many countries are still exploring how to better work with men in ways which create real change.

To move forward in PNG, there needs to be a continued commitment to support the sustainability of the country’s civil society organisations. Donors have played an important role in helping establish these organisations and providing ongoing funding essential to the growth of civil society in the country. Donors need to continue providing funding over a long period and avoid exiting before an organisation can sustain itself. Doing so can create serious unintended consequences. For example, if a safe house collapses it can undermine the effectiveness of the entire referral pathway for domestic violence services. In the case of HIV and Tuberculous exiting too soon from supporting organisations that assist clients to stay on life saving medication can lead to drug resistant forms of these diseases.

It is also important that donors don’t shy away from funding core running costs and that they find ways to support fostering public-private partnerships, raising income and accessing PNG government funding on an ongoing basis. These organisations also need ongoing help to set up good governance mechanisms and effective systems and capacity including finance and human resource management. Many local organisations are established by local leaders who have specific advocacy or service delivery skills, but lack leadership, management and governance skills which can be difficult to develop without support.

Importantly, donor requirements for funding applications, reporting and monitoring and evaluation should not be overly onerous, as this could set up an organisation to fail. International non-government organisations, including United Nations organisations, should be encouraged to prioritise building capacity and partnering with PNG’s civil society. Donors should avoid having international NGOs compete with local NGOs for limited donor funding.

The rise of civil society in PNG is a major success story and is the key to the growing movement to address family and sexual violence and other social issues. All partners need to continue to work together to ensure we foster a dynamic civil society, so we can continue to provide better services and support PNG to improve development outcomes.

Stephanie Copus Campbell is the Executive Director of the Papua New Guinean Oil Search Foundation that implements annual programs focused on health, leadership and education and women’s empowerment and protection.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.