The Dangers of Nuclear War Between North Korea and the US

The threat of war between the US and North Korea has continued to grow as both nuclear-armed states refuse to give ground and reflect on their shared security history.

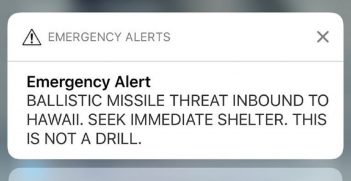

The world inches dangerously close to an armed conflict between the United States and North Korea, one which could all too easily tip over into nuclear war, either by design or by accident. In the past several months we have seen the stakes being raised, most overtly by North Korean President Kim Jong-Un’s confrontational testing of nuclear weapons and missiles, but also by US President Donald Trump. In his speech to the UN and on Twitter, Trump appears to contradict efforts made by his staff to reach a diplomatic negotiation to this crisis, suggesting instead a military solution, is now “fully in place, locked and loaded”.

However, there are other more proximate causes for this dangerous state of affairs. Chief among these has been the US insistence on continuing with its regular military exercises so close to the North Korean border, in conjunction with South Korean forces. These have been held for years, and North Korea—with some justification—sees them as highly provocative.

Earlier this year, Chinese leaders called for a freeze to these exercises, in exchange for Kim Jong-Un halting his tests. But this call was rejected by the US which claimed that even if Kim froze his nuclear and missile program, the US and South Korea were justified in their continuing demonstrations of military might. In late September, American B1-B strategic bombers flew perilously close to the North Korean border, something that clearly antagonises Kim, who sees the exercises as nothing less than a rehearsal for invasion.

American foreign policy has done little to disabuse Kim of this idea. The escalation is more than just a classic case of what international relations scholars call the result of a ‘security dilemma’, in which the actions of one state, even if they are meant to be defensive, can prompt adversaries to see them as threatening, leading to these adversaries putting forward military responses.

The poor record of American nuclear agreements

That US military exercises have been occurring on the Korean peninsula for decades is problematic enough, but the US record of following through on promised agreements with North Korea has been very poor. For a start, the US violated the terms of the armistice signed in 1953, by deploying approximately 100 tactical nuclear weapons in South Korea. The armistice required that only replacement weapons, on a piece-by-piece basis, could be brought onto the peninsula. The US violation of this promise did not bode well for subsequent relations with North Korea and eventually they were removed following the end of the Cold War.

In 1994, amidst growing fears of a North Korean nuclear capability, President Bill Clinton negotiated the Agreed Framework with Pyongyang in which oil supplies and two light-water reactors would be provided to North Korea in exchange for its halting of plutonium production. This was the first and only nuclear bilateral government agreement between the two states, and it had the potential to bring about an end to the Korean War, or at least to ease nuclear tensions considerably.

North Korea had been largely compliant with the Agreed Framework—although it continued enriching uranium, this was not explicitly prohibited under the deal. Nevertheless, Clinton’s Republican opponents despised the 1994 Agreement, and when they gained power in Congress they placed obstacles in the way of its implementation.

The election of George W. Bush in 2000, who took a hardline stance towards North Korea, further doomed the accord. His policy of hostility, hints of regime change, his labelling of North Korea as a member of the “axis of evil” against which the US claimed a right to launch a pre-emptive attack scuppered any good will that had been reached by Clinton.

This, and the failure to deliver the goods agreed to in 1994, saw North Korea renounce the deal. Not surprisingly, Pyongyang withdrew from the nuclear non-proliferation treaty in 2003 and commenced testing nuclear weapons in 2006. A promising opportunity had been lost.

We see a similar story happening now: Trump has disavowed the nuclear deal reached with Iran in 2015 by President Obama, the P5 states and the EU. His decertification last week of that agreement—against the pleas of security analysts and political leaders who demonstrated that Iran is indeed complying with its terms—jeopardises the chances of preventing Iran from gaining the bomb.

This is bad enough, but Trump’s renunciation of what was a painstakingly negotiated agreement with Iran is bound to leave North Korea wondering whether Washington is really serious about diplomatic solutions. Kim Jong-Un may well conclude that even if Trump was to engage in a brokered deal with North Korea, there is no guarantee that Trump would live up to his end of the bargain.

For his part, Kim Jong-Un has been highly provocative and has been rightly denounced by the international community. He has been acting recklessly and his continued defiance of UN resolutions and global norms sets the stage for a potential disaster. None of the above is to condone Kim’s nuclear and missile policies. But we need to keep in mind the record of US-North Korea relations before we insist that the blame lies entirely at his door.

Will it escalate to nuclear war?

It could. While it is hoped that nuclear deterrence between the two adversaries will hold and that neither will be reckless enough to launch a nuclear weapon, the dangers of strategic misperception and miscalculation are too high for anyone to be complacent. The parties can probably avert a nuclear war, but ‘probably’ isn’t good enough. There have been too many cases already when the world has come close to a nuclear confrontation or accident, and only an idealist would think that it can never happen. As Patricia Lewis, from London’s Chatham House notes, there have been “several occasions in which nuclear weapons were very nearly used deliberately”.

There are several dangerous scenarios which might play out were Washington or Pyongyang to resort to even a conventional weapons strike, and for this reason it is imperative that we seek a non-confrontational approach to ending this current crisis. Insisting that Kim dismantles his nuclear and missile programs before talks can be held will not work. Washington must be prepared to seek talks without conditions, at least in the first instance. Kim Jong-Un is not likely to refuse: North Korea has repeatedly called for direct talks with the US, a peace treaty and a guarantee that Washington will not attempt regime change.

What can be done?

There is an urgent need for inflammatory rhetoric to be wound back and for direct talks to begin. It will also be necessary for the US to engage in a process of strategic empathy, whereby officials understand the history of their broken agreements and the consequences of ongoing military exercises. A sustained dialogue that eventually brings in regional partners and builds a sense of trust, and the creation of confidence-building measures are badly needed. Only then might it be possible to work constructively with Pyongyang to dismantle and ultimately eliminate North Korea’s nuclear weapons.

There is no guarantee that this approach will work. But the policies that have prevailed before now have not worked either—at best they have simply added to the hostile environment and at worst they promise devastating military consequences.

Marianne Hanson is associate professor in the School of Political Science and International Studies at the University of Queensland. She is also the director of the Rotary Centre for International Studies in Peace and Conflict Resolution.

Dr Hanson spoke to AIIA Queensland on this topic on 24 October.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.