Cyclone Seroja in Timor-Leste: A Complex Crisis

Tropical Cyclone Seroja hit Timor-Leste, resulting in significant loss of life and displacement. The full fallout will depend not only on the natural disaster itself but how it interacts with the worsening COVID-19 pandemic and emerging political tensions in Dili.

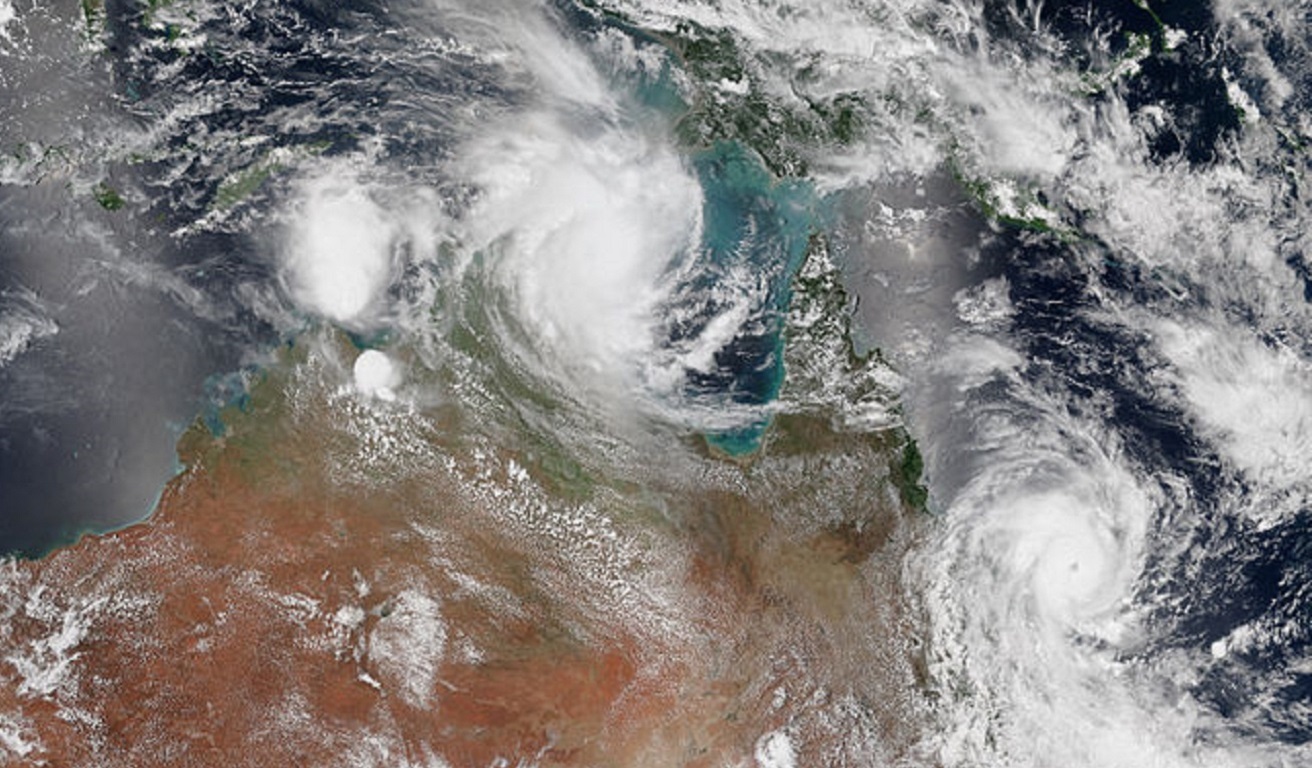

This week we have seen an unusual meteorological phenomenon, known as the Fujiwhara effect, where two tropical cyclones form in close proximity to one another and engage in a complex dance, making their trajectory and intensity difficult to predict. Across Southeast Asia, meteorologists tracked Tropical Cyclone Seroja as it ripped through Timor-Leste and Indonesia leaving devastation in its wake, eventually coming into contact with and subsuming Tropical Cyclone Odette. However, it is not only these cyclones that have interacted in unexpected ways. In the wake of Seroja, complex political and epidemiological crises are forming in Timor-Leste that have the potential to lead to a more serious political flashpoint.

Cyclone Seroja has caused some of the worst flooding the island has seen in decades, leading to the death of at least 42 people and the displacement of some 13,554 people in Timor-Leste. The capital city of Dili has seen unprecedented levels of destruction with bridges, houses, and roads collapsed in many locations. While reliable estimates of the damage will take weeks to tally, recovery and humanitarian assistance costs are likely to run into the hundreds of millions. This natural disaster has overlaid and compounded the developing threat of mass contagion from COVID-19.

Throughout 2020, the Timor-Leste government was hugely successful in preventing the spread of COVID-19. Strict quarantine measures were implemented, and the small half-island nation managed to last until February 2021 without any reported cases of local transmission. Despite best efforts, this trend proved impossible to continue, largely due to the challenge of managing the land border with Indonesia. In February, the first cases of COVID-19 outside of quarantine were detected in the border regions of Covalima. Since then, 983 cases have been detected, and the nation reported its first COVID-19 related death on 6 April.

To slow the spread, the government of Timor-Leste instituted a “sanitary fence,” effectively cutting travel between the capital city and other municipalities and imposed a strict lockdown across Dili. With little or no formal social assistance available, these measures have caused significant hardship across vulnerable populations. For many, staying at home means not being able to feed their family. Even before the floods, the resulting poverty and deprivation had led to widespread dissatisfaction and occasional protests.

Enforcing lockdown rules in Timor-Leste has been challenging. A lack of understanding about COVID-19, coupled with high levels of misinformation on social media, has meant that there are many who do not believe in the seriousness of the illness or the serious consequences that it could have on the people of Timor-Leste. Most positive cases detected to date have been asymptomatic.

The destruction caused by Cyclone Seroja has had a significant impact on the application of COVID-19 restrictions. The destruction that the city awoke to on Easter Sunday meant that maintaining lockdown was impossible. Neighbours and citizens rushed to aid each other as the devastating waters rose. Crowds congregated alongside rivers and bridges, watching as rivers carried houses, trees, and masonry in their wake. Tragically, the national medical warehouse experienced significant flooding, with stores of medication and personal protective equipment (PPE) destroyed. As a result of the cyclone, thousands of people are now living in evacuation centres, making social distancing and sanitary measures almost impossible. Many government officials, NGO staff, and volunteers have mobilised to provide much needed humanitarian support to communities, and the government has temporarily suspended the lockdown in the city. Not only are emergency response services allowed to open, but it appears that many businesses have taken advantage of the relaxed rules to open their doors. Many fear that the floods will act as a super spreader event and that Timor-Leste is likely to face large numbers of COVID-19 cases in the coming weeks.

As if this was not enough, Timor-Leste is now facing an emerging political incident involving the former president, prime minister, and beloved veteran leader Xanana Gusmão. On 12 April, a second COVID-19 death was announced. The government has strict sanitary protocols related to COVID-19 deaths and mandates that all those who die with COVID-19 must be buried at a state-run cemetery. The family of the deceased deny that he died of COVID-19 as he had been ill at home for some time with an underlying condition. They wish for his body to be returned to them for burial in accordance with their customs. Gusmão, whose party Congresso Nacional de Reconstrução de Timor (CNRT) is currently in opposition, became involved in the case and staged a protest outside the isolation hospital in Vera Cruz. Over the coming days, a series of interventions and visits from government officials, high-ranking members of the armed forces, and notable veteran fighters (Gusmão’s comrades in arms) failed to resolve the situation. Gusmão maintains that he will not leave until the body has been returned to the family.

While some spoke out against his actions, and members of government and the security forces have threatened the use of force, social media was inundated with a large outpouring of love and support for Gusmão, showing that he still holds significant sway over public opinion. A crowd of hundreds formed around the isolation centre, and police were called in to provide protection. The crowd is made up of family and neighbours of the deceased, political supporters of Xanana Gusmão, and members of CNRT, but also students and others dissatisfied with COVID-19 restrictions.

Gusmão has used the opportunity to rail against the current COVID-19 regulations, suggesting that he does not believe in the validity of the COVID-19 testing and, at one point, even advising the public not to go to hospital if they were sick. He has targeted the current government and most notably former Prime Minister Dr Rui Araujo, who is currently the head of the COVID-19 taskforce. Araujo is a member of FRETILIN, the largest political party in the country and main opponent to Gusmão’s CNRT. He was appointed prime minister of a national unity government in the aftermath of Gusmão’s resignation in 2015 and is widely rumoured to have future political ambitions that may not align with Gusmão’s own ambitions.

Much like the cyclone’s involved in the Fujiwhara effect, the full impact and trajectory of this incident is difficult to predict. It is likely that many of those who were disbelieving of COVID-19 will put more stock in the words and actions of Gusmão than in public health advice and that the work of public health officials will become more difficult. More significantly, while this incident can be interpreted as little more than a personal gripe over COVID-19 regulations, the position that Xanana Gusmão occupies as “father of the nation,” the underlying political dissatisfaction among Xanana’s own political supporters, and the political profile of those pulled into the saga suggest that this incident has the potential to become a more serious political flashpoint.

Méabh Cryan is a visiting fellow at the Department of Political and Social Change, Australian National University.

This article is part of the “Supporting the Rules-Based Order in Southeast Asia” project. This project is run by the Department of Political and Social Change at the Australian National University and funded by the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The opinions expressed here are the authors’ own and are not meant to represent those of the ANU or DFAT.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.