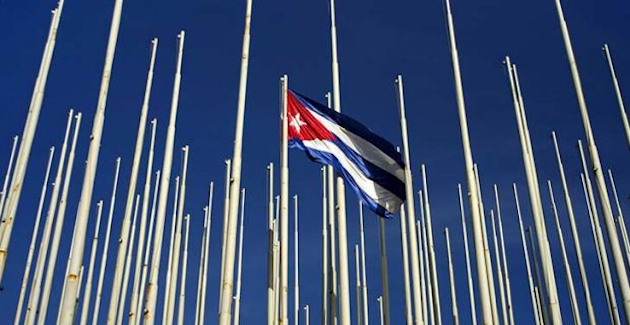

Cuba's Bipolar Engagement Offers Opportunity For Australia

This week, the Minister for Foreign Affairs Julie Bishop visited Cuba to promote Australia’s growing commercial interests in the Caribbean island nation. The visit is a sign of recent advances in Cuban diplomacy.

No longer hampered by the bipolar world of the Cold War, Cuba’s diplomatic efforts have come a long way. On the one hand, Cuba has reached out to the world with the advancement of bilateral trade agreements. In the last year alone, Cuba has seen trade volumes with China reach US$1.6 billion (AUD$2.1 billion), and Russia has cancelled 90 per cent of Cuba’s debt, amounting to US$32 billion. Russia and Cuba are planning military, intelligence, and naval collaboration, and Cuba has recently renewed its bilateral trade agreement with Venezuela with more than US$1.4 billion in investment.

However, among these advancements in trade, channels of communications and interconnectivity with people living outside Cuba is less progressive, with only 5 per cent of the Cuban population having access to the internet. As the Cuban government touts its plan to reform and revitalise the economy, companies in Europe and the US are anxious to invest in Cuba, but many doubts remain.

Economic reform in the direction of liberalisation has not materialised despite the assurances of President Raul Castro. Investors want more than just favourable tax concessions and special economic zones. Infrastructure, telecommunications and regulatory frameworks are the types of incentives that larger market investment participants are wanting to see.

Unique investment environment

In terms of human capital, a study by Boston Consulting Group notes that many professionally qualified Cubans living in the US claim that until there are significant political reforms they won’t return to Cuba to engage in joint ventures or start-up businesses. The private sector in Cuba is growing quickly, but the government’s reforms are not keeping up with market forces.

President Castro suggests that economic reforms are being implemented “without haste, but without delay,” but Cuban workers say that Castro is opening up the economy for his benefit and firing state employees too quickly for the private sector to absorb them. Lifelong public workers moving into an emerging private sector will experience insecurity and unrest, which is something the Castro regime has always wanted to avoid.

The private sector only makes up 27 per cent of the workforce and Cuban authorities continue to stall economic activity with bureaucracy, which inhibits local businesses from pursuing start-ups and results in an increase in parallel (black) markets. Making matters worse, economic supply is unstable, and fluctuating prices compromise the profits of small businesses.

For these reasons, many aspiring entrepreneurs and investors are afraid to put their money into the Cuban economy. The Peterson Institute for International Economics has previously described Post-Soviet Russia’s rush into capitalism as having yielded disastrous results because “the economy was captured by oligarchs and overrun with corruption”. The same could happen in Cuba, given its vast portfolio of state-run companies closely tied to the military and its entrenched bureaucracy.

Cuba is attempting to climb out of a 25-year trading slump and only in the last decade has it begun to recover from the economic damage that prevailed after the fall of the Soviet Union. It is no longer troubled by the Cold War era, yet opposite extremes continue to mark Cuba’s engagement with the world.

Cuba never recovered from the slide in domestic product per capita growth that began in 1984 and persisted through the 2008 global financial crisis. Official figures peg the annual GDP growth rate at 4.7 per cent, but the actual figure is likely to be lower, given the unreliability of official statistics.

The reasons behind this anaemic growth are well known; besides the lack of foreign investment, several structural issues blight the Cuban economy. Within the self-employment sector, the government only permits 201 types of job functions and these activities are reserved for skilled trades. Occupations that require a university education are rarely authorised for self-employment. The restrictions placed on those with advanced post-secondary education discourages them from investing their time and money in creating lucrative, breakthrough technologies.

Cuba is an unusual case as countries go, it is relatively poor in terms of GDP per capita but it has a high rate of human development and human capital. To experience growth rates like those experienced by Southeast Asian and East Asian economies, Cuba will need to free its human capital to enable its workforce to participate in products and services that can be exported to the world.

Another structural issue that needs urgent attention is a tax code that reduces incentives for new economic activity. The overall tax burden remains 24.4 per cent of GDP. However, this figure masks some deep problems with taxation in Cuba. While there is a notable absence of personal income taxes, corporate taxes, and value added tax, Cuba does tax private enterprises on the number of employees they hire. This is an impediment to increasing the number of workers and is a drag on economic growth.

Besides the issues of taxation and private sector regulation, another structural issue Cuba must address is its demographics. Cuba is facing a demographic crisis in the form of an ageing population and the loss of its younger citizens to emigration. Addressing the defects of Cuba’s economic system will go a long way in addressing at least one factor in the demographic crisis and the economic conditions forcing people to leave the island.

Given the structural issues facing Cuba, one wonders what the solution might be and the answer may lie in Cuba’s bipolar engagement with the world. Cuba’s close trading partners, such as China and Brazil, may provide the impetus for its leaders to make much-needed changes to its economy.

There is some evidence that the Chinese have persuaded Raul Castro to undertake some model reforms inspired by the China model. However, China’s reforms under Deng Xao Ping, which decentralised state power and empowered small enterprises, have yet to be replicated in Cuba.

The change will have to come from the top, as Cuba firmly remains a command and control economy. It’s to be hoped that as Cuba distances itself from countries like Venezuela, it grows closer to countries such as Australia and that its leaders realise the merits of fully implementing the economic and political reforms needed to bring prosperity to its people.

Fernando Rodriguez has a degree in economics and a master’s degree in international trade from Monash University. He has extensive experience in the resources and energy sector and has provided strategic advice and investment solutions to governments in Latin America, including Argentina, Chile, Peru, Bolivia, Colombia and Ecuador.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.