Costly Choices: Establishing the Facts of Australia’s China Policy Since 2016

With the relationship between Australia and China now in a stalemate and the possibility it could get worse, leading local protagonists have taken to telling a story of how things came to be. But it’s in no small part a self-serving tale, seemingly designed to deflect having to take some responsibility.

The starting point to be clear on is that, as former senior Singaporean diplomat Bilahari Kausikan has observed, Australia’s foreign policy challenge of having to manage a large economic relationship with China alongside a deep strategic and security relationship with the US isn’t unusual. Many countries, including Japan, India, Thailand, and the Philippines to name just a few, similarly must balance such interests.

The next point to recognise is that Canberra isn’t alone in having serious differences with Beijing. Indeed, the divisions between China and Tokyo, New Delhi, and many other capitals are even more acute. Yet despite this, it is Australia that is an outlier in having no senior-level political dialogue with China, in addition to the array of trade punishments it is being hit with. This raises obvious questions about whether in the face of China’s undoubted capacity for hypocrisy and bad behaviour, Australia got its strategy for handling the relationship right.

Former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, who was at the helm when the relationship with China began its downward spiral, wrote recently that the “Chinese strategy was to isolate Australia from its allies.“ He further assessed that “at the same time as Australia was being disciplined, Beijing sought to get closer to Japan and the United States.” This implies that the severing of political dialogue and trade strikes that now mark Australia as an outlier were not of its own making. Turnbull’s remarks instead argue Chinese strategists had settled on isolating Australia and that was that. This aligns with Prime Minister Morrison’s more recent claim that “Australia has done nothing to injure [the] partnership [with China], nothing at all.”

However, this version of events comes up short. First, it ignores occasions when arresting the decline, and potentially even turning the corner to a positive relationship trajectory, was within reach prior to the dramatic negative step-change in 2020.

On August 7 2018, just two weeks before he was deposed as prime minister, Turnbull delivered what Phillip Coorey, the Australian Financial Review’s Chief Political Correspondent, described as a China “reset speech.” Coorey noted it was “carefully written and planned to address an invited audience, which included China’s ambassador and consul-general to Sydney.” In responding to Turnbull’s intervention, which had praised China’s economic reforms and the benefits of bilateral ties, the Chinese foreign ministry said it had “noted and commended these positive remarks.”

On August 23 2018, the Australian government banned Chinese tech company Huawei from participating in the country’s 5G rollout. At the time, Scott Morrison took responsibility for the decision, then in the position of treasurer and acting minister for home affairs. When he subsequently emerged as prime minister, Beijing still extended an invitation to his new minister for foreign affairs, Marise Payne, to visit China in early November 2018 for the 5th Australia-China Foreign and Strategic Dialogue. Payne’s predecessor Julie Bishop went the last two and a half years of her tenure without setting foot there. As well, a year later, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang met Morrison for an annual leaders’ meeting on the sidelines on the East Asia Summit in Bangkok. Such moves are hard to square with a settled strategy of isolating Australia.

Second, the idea that Australia’s outlier status was inevitable ignores a series of national diplomatic choices over a period of years that were guaranteed to make China less willing to cooperate with Australia, while providing no offsetting national interest benefit. These included Bishop’s needlessly provocative Fullerton Lecture in Singapore in March 2017, in which after singling China out as a “non-democracy,” she then contended that “democracy and democratic institutions are essential for nations if they are to reach their economic potential.”

Then there was Turnbull’s inflammatory remarks made while introducing new foreign interference legislation in December that year. Delivered in Mandarin, Turnbull asserted that the Australian people had “stood up,” just as Mao Zedong said the Chinese people had done at the formation of the People’s Republic in 1949 following a century of foreign occupation and humiliation. As well, rather than pressing the point that the laws were intended to be country-agnostic, Turnbull chose to justify their passage by citing “disturbing reports about Chinese influence.”

Australia’s diplomatic positioning hasn’t only involved loose rhetoric. For instance, The Wall Street Journal reported that in recent years, Australian diplomats have “crisscrossed Europe connecting China critics in smaller nations with counterparts elsewhere,” adding that these efforts had “buttressed similar ones by Washington.”

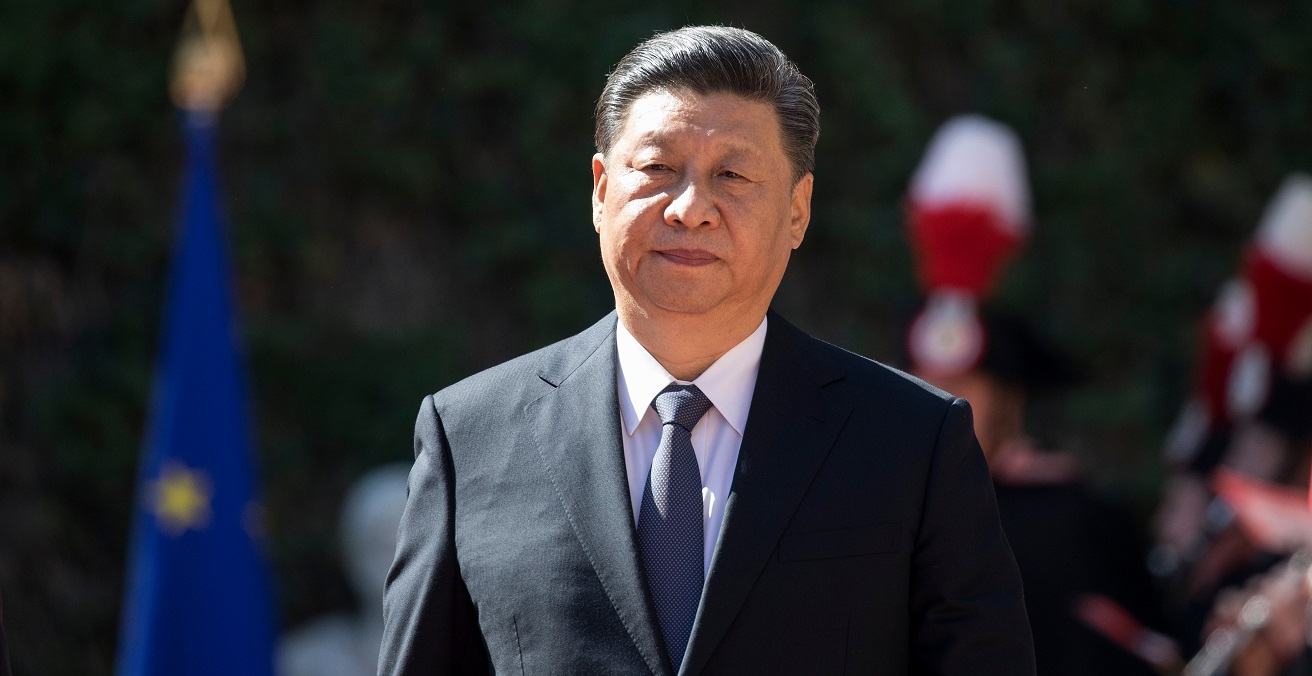

Third, even if other countries such as Japan were the subject of Beijing’s overtures, they also proactively took steps to maintain a balanced relationship with China. Tokyo’s approach to China, by contrast to Australia’s, has been anchored in careful, consistent, and clear diplomacy. Former Australian ambassador to Tokyo John McCarthy assessed that, “The Japanese are… careful about the tone and context of public statements about China, and the company in which these are made.” This can be illustrated in the fact Japan has sought to find areas where partnerships with China could be forged, even while retaining misgivings. On China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Tokyo University professor Asei Ito says that Japan moved from “non-participation” prior to 2016 to “conditional engagement” afterwards. Ito further assessed Japan demonstrated a willingness to work with China on projects in third countries. On a state visit to China in October 2018, Prime Minister Abe Shinzo and President Xi Jinping announced 50 joint infrastructure initiatives in partnership with China.

On the other hand, Australia appears to have moved from “conditional engagement,” signing a memorandum of understanding with China on cooperating in third countries in 2017, to “non-participation.” This can be reflected in the prime minister’s declaration in June last year that the BRI was a programme “Australian foreign policy doesn’t recognise,” with it not being in “Australia’s national interests.” This turn has extended as far as threatening to tear up a non-binding agreement on BRI cooperation signed by the Victorian government.

That ties between Tokyo and Beijing are now experiencing strain does not change the facts of Australia’s China policy since 2016. Abbreviated accounts of how Australia-China relations came to be in such a parlous state won’t fool China. And in the long run, they won’t serve Australia’s interests either.

Professor James Laurenceson is Director of the Australia-China Relations Institute (ACRI) at UTS. He has previously held academic appointments at the University of Queensland (Australia), Shandong University (China), and Shimonoseki City University (Japan). His research has been published in leading scholarly journals including China Economic Review and China Economic Journal. Professor Laurenceson also provides regular commentary on contemporary developments in China’s economy and the Australia-China economic relationship. His opinion pieces have appeared in Australian Financial Review, The Australian, Sydney Morning Herald, South China Morning Post, amongst many others.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.