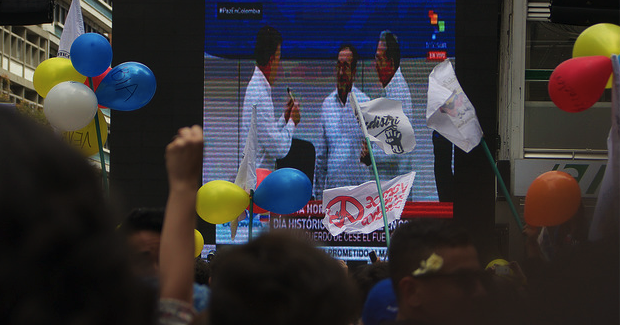

Colombia Celebrates a Second Independence

History will remember Wednesday 24 August 2016 as Colombia’s most important day after Independence Day. On this day, the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) reached a peace agreement that will change the lives of 47 million people. It marked the beginning of a new era after more than six decades of armed conflict that claimed over 8 million lives.

Colombia was a violent society even before the conflict started with the FARC. The civil war that started in 1960 between the state, the FARC and the extreme right-wing armed paramilitaries—supported by the terratenientes (landowners) and the state—has its roots in La Violencia. This was a civil war carried out between 1948 and 1958 when the Liberal party (representing the working class) and the conservative party were fighting each other for political power.

The FARC was born as a Marxist-Leninist guerrilla group, whose goal was to bring about land reform, redistributing land ownership among the peasants and the working class. The idea was to erase the latifundios (rural estates) and to enable equal opportunities for rural people through access to the means of production. The FARC was initially linked to the Liberal and Communist parties of Colombia. Thus, economic inequality and political participation have been at the root of more than half a century of conflict and have shaped the militarised and violent society that Colombia is today. This is why the recently signed peace agreement gives significant importance to rural development, extermination of poverty and political participation.

The peace agreement signed two weeks ago is the third major attempt in five decades to reach a negotiated solution to the conflict. In 1984, the government and the FARC reached a ceasefire agreement for first time, which allowed the creation of a new leftist political organisation as a first step towards the FARC´s demobilisation. However, in the four years that followed, more than 3,000 members of this political organisation, the Patriotic Union, were killed by the paramilitaries in collusion with the state’s military forces.Consequently, the ceasefire collapsed in 1987 and the peace talks in 1990.

Militarised society

Nine years later, the government and the FARC engaged in a second major series of peace negotiations. The government on that occasion agreed to demilitarise a territory the size of Switzerland in the Caguán region of Colombia were the talks were going to take place. This initiative collapsed in 2001 because of the low level of trust and because the parties became stalled in long conversations around procedures and were unable to address any of the substantive issues. In 2002, Alvaro Uribe was elected as the new Colombian president on his promise to wipe out the guerrillas through the use of military force.

During Uribe’s term, I witnessed Colombia become the most militarised it had ever been. The national expenditure on defence grossly increased and our dependency on the US to abolish cocaine fields became even more sickening. For eight years there was no budget for education, health or food, but an endless supply of funds to purchase arms to fight the guerrillas. While this military offensive was unable to defeat the FARC, it certainty triggered the peace negotiations that concluded with the recently signed peace agreement.

Although, the FARC were able to resist the government offensives they realised they would never achieve a military victory over the state. For the government, despite its success in turning the public opinion against the FARC, a military victory also proved to be elusive. The political context in South America also encouraged the parties to come to the table. Colombia´s neighbours had had leftist politicians ascend to lead their governments: Evo Morales in Bolivia; Rafael Correa in Ecuador; and Hugo Chávez in Venezuela. Countries such as Uruguay and Brazil even saw former guerrilla combatants become leaders, “Pepe” Mojica and Dilma Rousseff respectively.

The 2016 peace deal

Thus, government and the FARC came to negotiate peace for the third time. The preliminary talks were held secretly in Colombia in 2011 and by August 2012 formal negotiations were underway in Oslo and later moved to Havana, Cuba. The pact signed by the FARC and the government representatives comprises a series of agreements. The first of those is on integral agricultural development, in which land ownership rights are formalised and given to rural communities, and natural reserves are finally protected by the state. This agreement also encompasses social development and poverty eradication. The second agreement is on illicit drugs, the FARC has vowed to halt its involvement in the dug trade, restoring government control over regions were cocaine is grown and trafficked.

Point three of the deal is about transitional justice and victim’s reparations. Under this, a truth commission will be created to investigate everything that happened during the conflict; ex-combatants are required to tell all, which is a historic precedent that will allow for reparation measures for victims to begin. Those who admit to grave crimes—such as kidnappings and executions—will be subject to periods of restricted mobility for five to eight years, during which they will be expected to perform community service.

Those who have committed less serious crimes—like drug trafficking—will receive amnesty. This is perhaps one of the points that has been heavily criticised by those lead by ex-president Uribe, who are opposed to the peace agreement and believe it will inevitably leave many crimes unpunished and will give amnesty to the members of the FARC who committed grave crimes. Nevertheless, this point, if managed correctly, could allow many victims to have access to justice and reparation by having their day in court while holding war criminals—including members of the military—accountable for their crimes.

The fourth point of the agreement is about political participation. Members of the FARC will be allowed to run for office in legislative elections in 2018 and a minimum of 10 seats will be set aside in the senate and the house of representatives for ex-guerrilla combatants.

The fifth point involves a complete bilateral ceasefire and abandonment of arms. This section establishes the process by which members of the FARC will put down their weapons and re-enter civilian life. It also contains the clauses regarding the fight against the still existing paramilitary groups—BACRIM—that might threaten the ceasefire and the implementation of the peace. The last point is on a procedural issue dealing with implementation and monitoring.

Certainly, this agreement is a major milestone in the process of settling one of the world´s most protracted and violent conflicts. Colombia is showing the world that apparently intractable conflicts can be solved through political solutions. Yet, one of the biggest challenges ahead that could stifle change towards sustainable peace, is the way security is perceived and defined in the country. Security has been historically understood through logic of war, which maximised the different forms of violence faced by civil society on a day-to-day basis. Women and civilians have borne the consequences of rampant sexual violence, common crime, acid attacks, femicide, homicides, sex trafficking, hunger and unemployment. Colombia rates within the top 10 countries with the highest levels worldwide of inequality (7th), femicide (10th) and sexual abuse (more than 17,000 cases per year).

The journey of independence from the chains and burdens that war has imposed on Colombian society has begun. Patriarchy, militarism and violence need to be eradicated to be able to have a sustainable peace with a different development paradigm. This is the first time in our history that we will be able to say yes to a new beginning. On 2 October, Colombians will get a chance to vote in a national referendum to endorse the peace. It is time for Colombians to shift the understanding of security to one that encompasses human security.

Alejandra Pineda holds a bachelor degree in international relations from La Trobe University and has a graduate certificate in conflict resolution and peace building from Johns Hopkins University.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.