China’s New Era Under Xi

It is crucial to understand the radical nature of Xi’s project to understand a changing China.

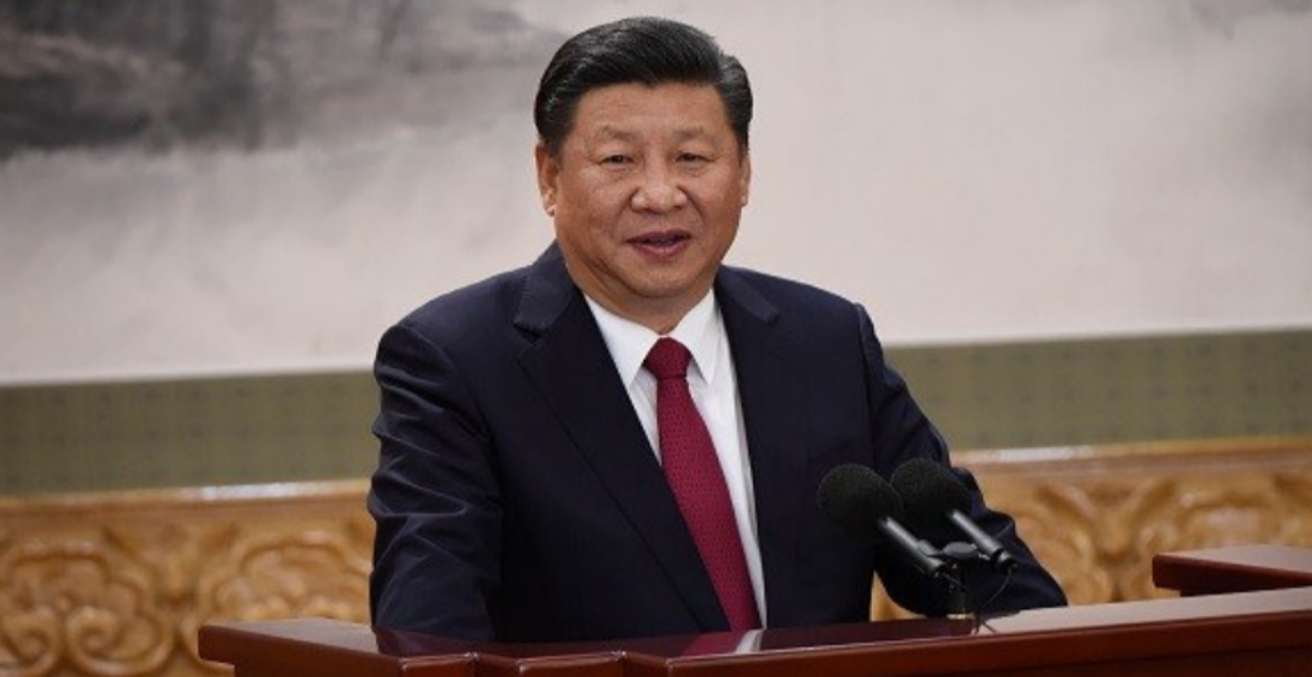

We have all watched agog, these last 18 months, the shaking up of America under Trump. But a far more significant, radical and enduring transformation has been under way. The nature and scale of Xi Jinping’s ambition, and the extent of his success in implementing it at home and increasingly internationally, are breath-taking.

China has in recent months written into both its communist party and national constitutions, “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era.” How this plays out for your studies, your career, your company and your country, is of central importance.

How to parse this Xi Thought? His three and a half hour speech at last October’s five-yearly party conference provides the key text. Those who seek to engage with China today need to read it seriously, if they are to be taken seriously.

When Xi emerged as general secretary in 2012, he was viewed as a consensus kind of guy like his immediate predecessors. This proved totally wrong. Instead, Xi has destroyed all individual rivals, rival families, power blocs and factions. He is now called by state media “helmsman of the nation.”

Politics professor at Oxford Stein Ringen calls Xi’s rule a “controlocracy.” Most people go about their daily lives as they please, provided they are able to accommodate to limitations on liberty. There is no institution in China that is neither directly led by nor accountable to the party, or that the party does not have the capacity to direct if required. The recent National People’s Congress amended Article 1 of the national constitution by adding the explicatory sentence: “The defining feature of socialism with Chinese characteristics is the leadership of the communist party of China.” Thus, the party has been brought directly into the main body of the constitution for the first time. A multiparty system may thus be deemed unconstitutional, while the rights accorded under the constitution have been made unappealable thanks to the party’s primacy under it.

Xi’s Era is one of centralisation of decision making, restructured around party commissions, formerly known as ‘leading small groups’, such as on security and on the Internet, six of which Xi personally chairs. They have effectively replaced the Politburo Standing Committee as the locus of real power. But we know far less about the personnel or the processes around the commissions than we do about PSC meetings. Typically, I noticed Xi recently chaired the central auditing committee responsible for all party and state audit operations; there appears no technical area that he believes to lie beyond his grasp.

There is no separation of powers in China, of course. Xi views government workers essentially as hired help, and has just dragged a lot of important areas from government to direct party control. Xi is installing a National Supervisory Commission to extend to every government official at every level, the purge within the party of rivals and of “disloyalty” – under the formal goal of “anti-corruption” – that has delivered him even greater authority than Mao Zedong. The intense, energetic campaigns by the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection over the past five years, Xi has said, “cut like a blade through corruption and misconduct.” This was his key tool in achieving such unassailable personal control over the party so rapidly; any word or act of dissent might trigger a CCDI raid. As an unintended consequence, though, this campaign has broken up many networks of trust that had driven business activities for decades.

Xi is utterly sincere. He is not a pragmatist or “realist”. He has a relentless work ethic and has taken over day-to-day direction of every important policy area. He has identified China’s “three tough battles”: preventing financial risks, reducing poverty and inequality and tackling pollution. He has also warned against seven deadly sins. They are: to promote constitutional democracy, universal values, civil society, economic neo-liberalism or the Western concept of a free media; to deny the party’s official narrative of history; or to question the nature of Chinese socialism.

Xi has helped transform the Internet, in the name of “cyber sovereignty,” into a great tool of control, delivering him broader and deeper power over the population than Mao could have dreamt of. In the “real world,” each 200 Chinese households are to be monitored closely by a security manager via the “grid management” system. This is being augmented by the new “social credit” system whereby people who jaywalk or smoke on trains and so forth risk being tagged by CCTV and by great facial recognition software, and may be banned like those who in the “virtual world” sign petitions or, say, post critical items online, from travelling, forbidden state jobs, denied promotion, etc – while those who act worthily will gain advantaged “green channel” access to jobs, travel and leisure. China has 200 million surveillance cameras, four times as many as the US. A further 100 million are planned by the end of 2020. Martin Chorzempa, a fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, says: “The goal is algorithmic governance.”

Xi has smashed domestic dissent, chiefly through a single masterstroke three years ago with the nationwide overnight arrest of hundreds of lawyers and their staff whose practices had focused on rights cases. The marginalised have thus lost their intermediaries, while China’s embryonic civil society is cowed and in retreat. The extraordinary administrative efforts of the heightened control being applied in this New Era are seen not only in grid management, social credit and the Great Firewall, but also in regions such as Xinjiang, where half a million Uighurs have been detained in new re-education camps.

Xi is a healthy-looking 65, and may well wish to continue ruling for a further 20 years or more. He is not grooming a successor. Xi will preside over the 70th anniversary of the PRC next year, and in 2021 the centenary of the party itself. Chinese people are naturally proud of what China has achieved. So long as Xi continues to score successes, they will be grateful. But, as sinologist Andrew Nathan warns, “if he stumbles, they will turn on him.” I must stress there is no hint of that so far, although the centralisation and personalisation that constricts advice to a very narrow and hard-to-approach circle do create potential new risks for the party down the track. The party has placed all its eggs in the Xi basket, and if he fails then the party will face a mountainous task to re-establish its credibility no smaller than it faced in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution at the end of the Mao era.

Rowan Callick OBE FAIIA is an Industry Fellow of the Asia Institute in Griffith University. He has recently returned from Beijing as The Australian’s former China Correspondent and has held positions including The Australian’s Asia-Pacific Editor and The Australian Financial Review’s China Correspondent.

This is an extract of his speech at AIIA VIC on 23 August 2018. Further extracts will follow.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.