China’s International Influence

China under Xi no longer looks to Soviet or Western models, but exudes confidence in its own model.

This article is the last in a series of three based on the author’s talk to AIIA VIC.

Xi’s China is supremely purposeful. In Xi’s New Era, he wants China’s economic heft to be reflected in international influence and respect and in a capacity to transform global institutions to better suit its own ambitions. Its population is travelling, studying and investing globally; Xi is assuring that population that Beijing will promote and protect them and their interests in full.

Politics professor at Oxford Stein Ringen wrote recently that “under Xi’s leadership, the People’s Republic is coming into its own. Xi is promoting its ‘model’ in the world as superior in delivery and problem-solving to what is seen as dithering democracy. He believes in the mission of Chinese greatness in the world. Xi’s political project is audacious.” It no longer looks to Soviet or Western models, but exudes confidence in its own model.

As prosperity becomes more routine within China, Xi has needed to identify a fresh channel of legitimacy for party rule, China’s international authority, which can be audited readily by the hundreds of millions of Chinese who travel internationally. He spoke during the Party Congress of China’s system now providing “a new option for other countries… which want to speed up their development while preserving their independence.” China’s own rapidly spreading influence is being hinged not only off such ideas, but also off the economic interdependence through which it has become the number one partner in trading goods of most of the world.

Evidence of the higher priority given by Xi to international affairs was provided by the elevation of the top foreign affairs leader, Yang Jiechi, to the Politburo, and more potently by the election by the National People’s Congress in March of Wang Qishan as vice president. Wang is Xi’s closest political ally. The vice presidency is a meaningless position domestically, but potentially important internationally. One might surmise that Wang is taking on such a role because foreign affairs is climbing to the top of Xi’s priorities.

Last year, indicating both anxiety and confidence about “going out”, a patriotic Chinese Rambo style movie, Wolf Warrior 2, smashed box-office records. The film’s slogan, adapted from a Han Dynasty saying, is: “Whoever offends China will be punished, no matter how far they are.”

Or how close. The mountains may still be high, but the emperor is no longer far away. He is omnipresent. Xi’s visit to Hong Kong for the 20th anniversary of the handover last year revolved around the big set-piece of his inspection of a large People’s Liberation Army (PLA) parade, sending a clear message. His era is new in part because of its clear break with the era of Deng, who devised the one-country-two-systems formula for Hong Kong that was for long touted as a model for Taiwan. Those days are now over.

Xi gave no time to the highly pragmatic Tsai Ing-Wen to demonstrate that she intended to run Taiwan in a very different way from her predecessor Chen Shui-bian, instead tightening pressure especially through military flights and sailings. Last month, El Salvador cut its diplomatic ties with Taiwan after demanding a huge amount of money, which President Tsai refused to discuss. This is the third country that Beijing has persuaded to shift its loyalty this year, leaving only 17 remaining. While stressing his championing of globalisation, Xi also refused from the start to countenance any role for the International Court of Arbitration over the South China Sea controversies, establishing armed bases on islets there despite saying three years ago during a White House visit that “China does not intend to pursue militarisation” in the South China Sea.

Asian concerns over the reliability of Trump are reinforcing Xi’s hand. Japan’s wily leader Shinzo Abe is stealthily rebuilding relations with China, as is South Korea’s Moon Jae-in. And just when it appeared China was being frustrated in gaining a core role in the fast-moving North Korea denuclearisation saga, Kim Jong-un travelled to Beijing and then to Dalian to meet Xi. The brief document signed in Singapore is claimed by Beijing – rightly, I believe – as directly meeting its own proposal.

Xi has modernised the PLA, cutting its size by 300,000 to two million while it establishes overseas bases, the first in Djibouti, and patrols distant oceans as far as the Baltic Sea. It stands ready to break free of its former constraints within the “first island chain” in the Pacific. Immediately after his recent speech at the Bo’ao Forum, Xi went on to review China’s biggest military exercise in the South China Sea, involving 48 warships, 76 fighter jets and 10,000 naval personnel. China’s fleet is now bigger than America’s in sheer numbers.

Xi is boosting China’s diplomatic resources massively. Since 2013, its foreign affairs spending has almost doubled. Xi established China’s first aid agency this year, tasked “to better serve China’s diplomacy, and the Belt and Road Initiative,” the BRI. This month, every African leader flew to Beijing for the second Africa-China Summit, underlining which power wields most influence in that continent.

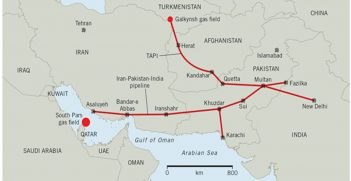

Xi’s BRI is acting as a great magnet for countries short of capital and infrastructure. It is being engineered to help ensure that not only all roads, but also all rail, air and sea routes, all compliance arrangements and technical standards, all telecommunications carriers and all leading Internet platforms lead not to Rome but to Beijing as Eurasia’s connectivity hub. In certain strategic cases, as massive loans prove unsupportable, Beijing has begun to forgive the debt but assume the assets, such as ports in key locations including Sri Lanka and the Maldives. IMF managing director Christine Lagarde recently said that while the BRI could provide much-needed infrastructure, such ventures “can also lead to a problematic increase in debt.” Malaysia’s sprightly new leader Mahathir has launched a review of BRI projects, using the phrase “unequal treaties,” which he would be well aware carries deep resonance within China.

China’s expanded regional and world role under Xi has encouraged Hun Sen in Cambodia and the military in Thailand to shrug off the need for real elections, and has emboldened the military to revive their grip in Myanmar.

Xi was applauded wildly by the international elite at Davos 18 months ago as the new champion of economic globalisation. China has recently convinced the UN’s 47-member Human Rights Council to accept as its new template Xi’s formula of “a community of shared destiny for human beings,” supplanting the former adherence to universal values. Xi has also presented himself as the global champion in areas from climate change to global health and from international peacekeeping to anti-piracy.

Our lives are changing in extraordinary ways. Xi’s New Era for China and for the wider world challenges us all to interrogate what Xi wants, and the degree to which this coincides with our own ethos and goals, and to consider how best to relate with his China in a way that produces net mutual benefits. That is the formidable task facing all of us.

Rowan Callick OBE FAIIA is an Industry Fellow of the Asia Institute in Griffith University. He recently returned from Beijing as The Australian’s China Correspondent and has held positions including The Australian’s Asia-Pacific Editor and The Australian Financial Review’s China Correspondent. He is a Fellow of the AIIA.

This is an extract of his speech at AIIA VIC on 23 August 2018. Read the first article here and the second article here.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.