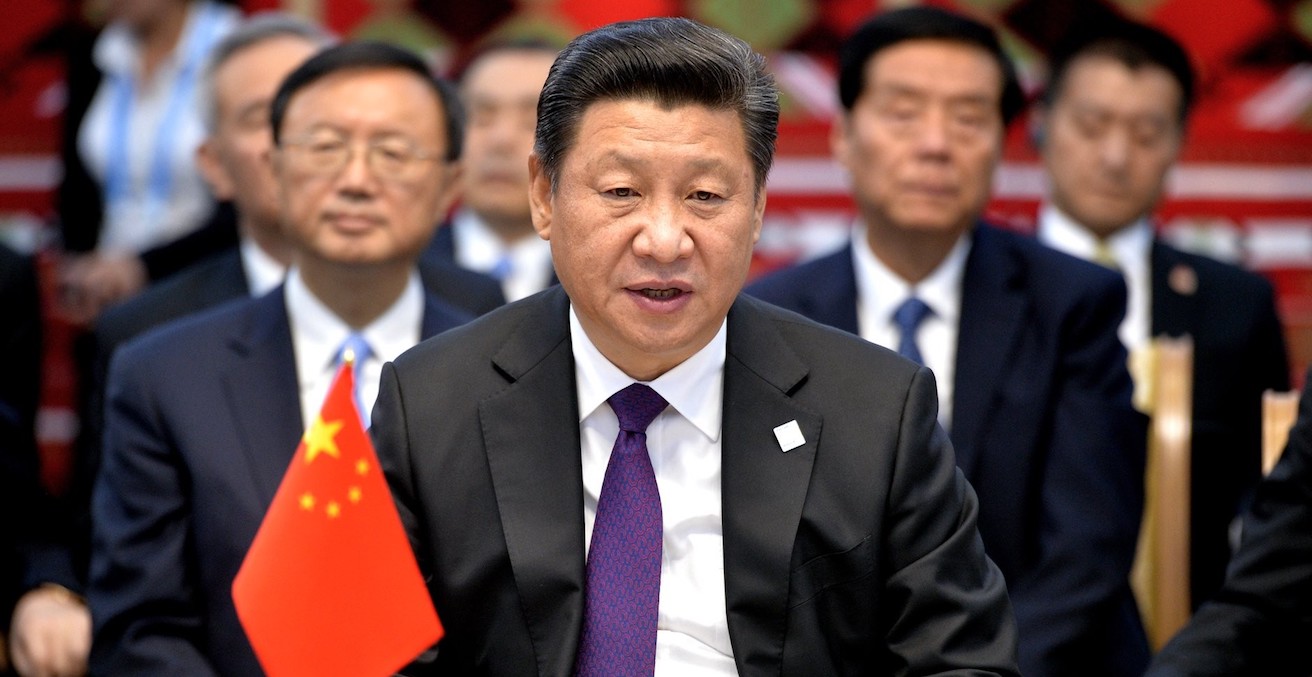

China is Limitless but What of Democracy?

On Sunday, the National People’s Congress voted to extend the limit of Chinese presidential terms indefinitely. The vote was expected to go without a hitch and it did, with only two “no” votes and three abstentions. Xi Jinping’s hold over China is assured for many years to come.

It is difficult to name an individual who has accumulated more power than Xi Jinping in living memory. Certainly, US presidents are popularly listed as the most powerful people on the planet, yet this power has always had a sunset clause: it cannot be sustained. This has generally been a good thing.

So many wars have been fought over the succession of power that it is not worth listing them. It may be a gross simplification, but democracy was the great innovation developed to deal with this problem. Democracy may have its weaknesses, but its true strength has always been the peaceful transition of power. Placing term limits on absolute power almost always works out better for those who live in its proximity.

China’s governance system no longer has the structural capability to transition competing power distributions. This is important; it’s perhaps the most important political development of 2018, if not the decade. Xi is the man who will make or break the future of China. The patron-client relationships he has cultivated over decades will now be entrenched throughout the world. This has dynastic implications.

This global evolution in governance systems is occurring parallel to the decadence of democracy. Engagement in mainstream political parties is at all-time lows across the Western hemisphere. Youth have all but given up on their democratically-elected politicians as the disconnect between political rhetoric and political action haemorrhages in a 24-hour newscycle.

For the first time since the Cold War, democracy has a competing governance system and that governance system is China. Since the Global Financial Crisis, this competition between modes of governance has only increased. East Asia became the Asia-Pacific, the Asia-Pacific became the Indo-Pacific; each time policymakers redrew the map, the borders of this competition grew.

You don’t have to look far to see its consequences: it’s in a Turnbull policy announcement on Twitter; it’s in a call of fake news by a no-name senator; and it’s written across the ways of identity politics. Developing nations the world over shop around for models of governance; they don’t always do this overtly—like asking for help on drafting a constitution—and often these movements are very soft, such as a small legislative shift based on the prevailing popular attitudes.

The removal of limits on Chinese presidential terms is dangerous because it affirms the status of term-less heads of state and heads of government across the world. It has normalised a form of governance that creates and inflames conditions of civil unrest and civil war. All this at a time when Western examples of democracy are at a very low ebb.

Trump in the US, Brexit in the UK, instability in Europe: where do you go for a good example of a functioning democracy when China is your yardstick? Where is a democracy that is generating annual GDP growth akin to China? Where is a democracy that walks with similar confidence and expectation of greatness as China? It should be no surprise that countries like Cambodia are sliding away from inherently democratic values and democratic modes of governance. Likewise, elections such as that held in Kenya last year should be expected more often.

Democracy’s fourth estate no longer holds the power and prestige it once had. In the US, disinformation, dark advertising, false truth and the internet of influence are weapons wielded by outsiders to weaken the system. In China, these are tools used by the state to strengthen the dominant distribution of power. To which model should developing countries look? To which model will they look?

The next time a prime minister or president is answering a difficult question from a pesky journalist or dealing with a false truth inspired by the foreign memes of faceless actors, what will they think? What policies might they decide to implement when a politically opportunistic event presents itself?

The true danger of this policy shift in China is the impact it will have on modes of global governance, particularly in Southeast Asia. Confidence and expectation define the nuances of daily diplomacy and personality plays a role. Five years down the track or 10 years, there is the potential for a Chinese president who has been president longer than any other head of state in the region. A Chinese president fuelled with the belief that the Middle Kingdom must and will be returned to its rightful place at the centre of the world. Try negotiating with that in 2025.

It is unlikely that China is going to tear itself apart in a civil war when Xi does decide his time has come. However, it is impossible to say the same about every other country that might adopt a Chinese model of governance. Not every country that slowly drifts towards a Chinese distribution of power will have the maturity to sustain that system. Coups, political witch hunts disguised as corruption crackdowns and the winding back of journalistic freedoms will be the symptoms of an anti-democratic slide. All the while, countries that engage in this practice will be able to play the US against China and Russia against the EU, extracting international resources while securing their hold on power.

Xi is here to stay. His vision of the future will not only make or break China, it will make or break the world. The competition for influence over those rare people in a position to steer the governance systems of their country has well and truly begun. China’s move has made it that much more likely that the political instability of power transition will become an even more regular fixture.

Thom Dixon is the Vice President of the AIIA NSW and a commissioning editor for Australian Outlook. He works as the research engagement and impact coordinator within the Office of the Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Research) at Macquarie University, Sydney.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.