Changing the National Conversation About China

Australia needs to unravel several different issues with foreign interference but the proposed legislation succeeds only in straining diplomatic ties with China and weakening political participation. Australia would be better to strengthen its democratic structures and expand its diplomatic role in the region.

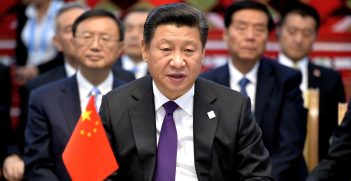

The current national conversation about China needs to be reoriented and its tone defused. Debate about the government’s proposed foreign interference legislation has been shadowed by an array of other matters: from reports on China’s blocked investment in Ausgrid, to Minister for Foreign Affairs Julie Bishop’s objections to China’s increasing militarisation of the South China Sea, to Labor’s Michael Danby’s comparison of Xi Jinping to Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm.

In the surrounding commentary, the object of concern has been slippery and shifting.

We need a conversation that is specific about the problems we do face and is effective in our response. The foreign interference legislation achieves neither of these objectives. Instead, it lumps together a whole raft of disparate issues under the amorphous label of “interference.” As a result, it strains diplomatic ties with China, threatens to undermine the very democratic structures it purports to protect and fails to meaningfully address the weaknesses that Australia’s democratic institutions do have.

Foreign interference in our politics, universities and media

Amid all the talk of the perniciousness of influence of the People’s Republic of China on Australian politicians, the response should actually strengthen our political system rather than weaken it. For all its posturing, the government’s legislation does little to redress the problem of money and influence in politics. The fact is, foreign entities comprise a tiny fraction of political donors. In 2015-16 they contributed only 2.6 per cent of total donations to the two major political parties.

While we do need a ban on foreign political donations, it must be decoupled from the current debate about foreign interference and instead become part of a wider sweep of measures that strengthen Australia’s campaign finance laws. Australia has some of the weakest campaign finance laws amongst developed nations. Instead of legislation that significantly impairs the ability of charities to participate in our political processes, we should establish a federal Independent Commission Against Corruption to oversee and act upon corruption in politics. Moreover, we need to drastically reduce the threshold for public disclosure of all political donations no matter where they come from. Currently donations of up to AUD$ 13,500 are kept hidden from public view.

In the education sector, if there are genuine instances of speech being silenced or pushed in certain directions, they must be specified, made public, and then addressed head-on. A photograph showing an academic or a political figure with a member of the United Front, an agency of the Chinese Communist Party, is not proof that any influence efforts—if they’ve even occurred—have been effective. So far, guilt-by-association seems to be the only accusation.

Concerns about interference in Australian media have centred upon the Chinese Communist Party’s increasing influence on Chinese-Australian outlets. But just because China’s state media has a platform, does not automatically mean it has a direct impact on its audience, who naturally respond in a variety of ways. The foreign intervention legislation risks weakening the Chinese-language media options available in Australia and has fuelled a dialogue that alienates Chinese-Australians and treats them as homogenous. Instead, we need to expand the options for Chinese-language content through incentivising schemes that would encourage bilingual production amongst all media outlets. This would be a step towards repositioning Chinese-language media so that it is not siloed from English-language media outlets but an integrated part of the media landscape.

Foreign investments

Against this backdrop, MPs on both sides of politics have lobbed warnings about Chinese companies seeking to invest in Australia, tapping into a long history of fears of foreign investment: from the United States and, later, Japan. Claims against Chinese companies such as Huawei or ZTE emphasise their connections to the Chinese Communist Party. Is the problem the fact that these are companies with ties to a foreign government? It shouldn’t be as this is a common part of the international investment scene. The French company Engie, for example, is one the largest providers of energy in Australia and just over 24% of its shares are owned by the French government.

Is the problem, instead, that China is governed by an authoritarian regime? If so, then we need to be specific about what makes investment from such a regime a concern. Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund, which under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has sought to expand its activities, doesn’t engender the same response here in Australia. Nor should it.

A more important question to ask in this debate is whether the investment is going to give the foreign government access to information or capabilities it wouldn’t have had through regular espionage means. The answer is almost always no. And when the answer is more complicated, as in the case of Ausgrid, we now have the newly-created Critical Infrastructure Centre designed to address any national security complications.

Increasing Australia’s foreign aid budget

The real issue, of course, is that China under Xi Jinping has become increasingly assertive. And the unpredictability of the Trump Administration has thrown into sharp relief the necessity of genuinely grappling with what Australia’s long-term foreign policy vision looks like. But at the same time that we have the largest peacetime defence budget, the Turnbull Government has slashed our foreign aid budget, which is now at its lowest level in Australian history.

Now more than ever, as China continues its militarisation in the South China Sea and breaches international law, Australia must move from a reactive to a proactive foreign policy. This cannot be achieved by lopsided expenditure that expands defence while cutting aid. Instead, we should be expanding our diplomatic role in the Indo-Pacific region.

The conversations we’re having here in Australia are part of and informed by conversations happening globally. While the Turnbull Government and the legislation’s supporters claim that our foreign intervention bills provide a model for other countries, they don’t address the real problems we do have in our political system. Instead they muddy and inflame the broader conversation about China at a time when Australia’s foreign policy is at an inflection point.

We need a nuanced and considered debate about our place in a rapidly changing Indo-Pacific region. We need a conversation about China that unravels the very different issues at stake. We need targeted legislation that will strengthen our democratic structures and expand our diplomatic role in the region. Only then will we become a true model in our region and beyond.

Dr Elizabeth Ingleson is an American historian at both the United States Studies Centre and History Department at the University of Sydney. She has also published on political interference on ABC Online.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.