For the Central African Republic There Will be no Peace Without Justice

The government of the Central African Republic has signed a peace deal with 13 rebel groups to bring an end to violence that has plagued the country since 2013, but what the prospects for success?

There has been a series of conferences, summits, agreements and plans for peace in the Central African Republic in the past five years, yet instability in the republic continues. The most recent agreement, signed in June, was no different. The day after it was signed, there was an upsurge of violence in the country’s eastern provinces.

The Central African Republic shares a border with six other African countries: Chad, Cameroon, the Republic of Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan and Sudan. It has a population of 4.6 million people.

Since 2013, the country has been embroiled in a civil war that has left half the population in urgent need of humanitarian assistance, and displaced nearly 1 million people. Half of those have sought refuge in neighbouring countries. Citizens also have to contend with economic desperation on a grand scale. The country is the lowest ranking country in the world on the Human Development Index.

Humanitarian actors, religious leaders and political activists believe that peace won’t come to the country until the perpetrators of violence are brought to justice. There is also the need to knit communities back together again. To this end, a national peacebuilding strategy has been developed. Its first pillar is about renewed trust between the people and the government. But there is no clear pathway for how this will happen.

Pragmatic developments on the ground are bringing about some change. Concerted attempts by humanitarian actors to sensitise community members about peace and tolerance has led to renewed trade and freedom of movement in the capital Bangui, and in many rural areas of the country where the fighting has now diminished.

But much more needs to be done before citizens of the Central African Republic believe that they can build a peaceful future together.

The civil war

Fighting broke out in late 2012 when the mostly Muslim opposition alliance, ‘Seleka’, attacked three towns. A year later it overthrew President François Bozizé. Meanwhile, Christian-led militias known as the ‘anti-Balaka’ began a brutal backlash against Muslim civilians.

Rebel leader Michel Djotodia declared himself president but he was unable to ensure a peaceful transition to a unity government and resigned in January 2014.

After a period of transition, elections were held in December 2015 with Faustin-Archange Touadéra assuming the presidency in March the next year. But unrest continues to this day, and has displaced more than half a million people internally, with close to 400,000 fleeing abroad.

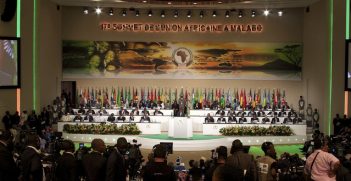

There has been a series of conferences, summits, agreements and plans for peace. These have included a meeting in Brazzaville in 2014 where National Reconciliation Talks resulted in a ceasefire agreement with the main militias. But this was never adhered to by militias on the ground. A 2015 Kenya conference also included a ceasefire agreement and a transitional roadmap; it was signed by the main militias but not adhered to on the ground.

Under the June agreement armed groups were offered political representation and incorporation into the country’s armed forces in exchange for a countrywide ceasefire. The day after it was signed, however, there was an upsurge of violence in the eastern province of Bria.

No justice

More than four years into the conflict, the perpetrators of war crimes have not been brought to justice and militias continue to attack civilians with impunity.

From my experience on the ground, residents are hesitant to welcome displaced families back into their communities because some of those families are part of the very militias who attacked them.

Arnaud Yaliki, former Permanent Secretary of the Central-African Interreligious Platform, explained the impact that these memories of civil war have had on civilians:

Imagine someone killed your relative and was not condemned. Grudges are kept and maybe you will kill to avenge their death. Thus starts a cycle of violence. There is some desire for revenge and a lot of grief.

The issues surrounding returnees are a strong indicator that the Central African Republic won’t be able to move on without justice. Nearly 20 per cent of the country’s population are internally displaced or refugees; provision needs to be made for them to reestablish their livelihoods if and when they return.

Humanitarian actors are investing heavily in social cohesion, as well as projects designed to promote dialogue and peace messaging. But fear and mistrust remain the dominant emotions among the citizenry.

The Imam of PK5, which is a Muslim-majority neighbourhood in Bangui had this to say:

It seems like the only solution now is weapons. People are not going to wait for MINUSCA [the UN peacekeeping mission in CAR]; they are going to stand up for themselves. Even with disarmament, they will go out and get another weapon, because they want to be able to defend themselves.

Efforts at peacebuilding

Understanding that its citizens are beginning to lose all hope, the government is implementing a national peacebuilding strategy, with the assistance of the United Nations. This, combined with concerted humanitarian efforts to sensitise community members about peace and tolerance, has led to a few positive developments. One is renewed trade. From my personal interactions with people on the ground, citizens are now eager to tell outsiders that there is tolerance and social cohesion in their communities.

Take PK5 for example, which is the sole Muslim-majority neighbourhood in Bangui. Before 2013 it was a vibrant commercial centre. But when the conflict began the neighbourhood was almost entirely cut off from the rest of the city. Even after the militias were driven out by the peacekeeping troops residents were still afraid to leave the neighbourhood.

It was commerce that finally facilitated their restored movement in the early months of 2017. They reopened their shops and attracted customers from elsewhere in Bangui. Then they leveraged their economic activity to trade for safe passage around the city.

A great deal of progress has been made in building a post-conflict society. What remains, however, is to address the memories, underlying fears, and suspicions. The various peace accords do not have provisions to bring the perpetrators of the war crimes to justice.

It will be impossible to promote peace without a functioning justice system. While the government has the will, it doesn’t have the means to implement a transitional justice programme.

Without creating space for truth telling, and assuring citizens that the perpetrators of violence will not go unpunished, the citizens of the Central African Republic will continue their struggle to welcome returnees, lay down their weapons, and withdraw support for militias.

Kathryn Kraft is lecturer in International Development at the University of East London.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation on 21 August and is republished with permission.