Castle Bravo: Marking the 65th Anniversary of the US Nuclear Disaster

Sixty-five years ago, the United States conducted the Castle Bravo nuclear test in the Marshall Islands. The blast spread radioactive fallout across a number of Pacific atolls and left a devastating legacy.

At 6.45am on the morning of 1 March 1954, Marshall Islanders are said to have woken to the sun rising in the west. The detonation of the Bravo shot at Bikini Atoll was estimated to have been 1,000 times as powerful as the bomb dropped on Hiroshima and was the largest nuclear device ever tested by the United States. It was also its worst nuclear disaster.

In the aftermath of the explosion, inhabitants of the neighbouring atolls, US servicemen and a passing boat of Japanese fishermen were exposed to radioactive fallout. The nuclear debris that coated the surrounding atolls caused generations of health problems and left a dark legacy which has shaped the small archipelago’s national consciousness.

The United States originally selected the Marshall Islands as a site for its nuclear testing at the end of World War II. Initially wanting to test the effects of its newly developed weapons on naval vessels, it sought a remote, sheltered location with stable weather that was in reach of its heavy air bases. The low-lying archipelago of five islands and 29 atolls in the North Pacific met these requirements. It had been occupied by the United States during the war after they pushed out the Japanese forces in the Pacific campaign. In 1946, the United States relocated the 167 residents of Bikini Atoll to the less hospitable Rongerik Atoll and with much fanfare invited the press and representatives from around the world to watch the two Crossroads nuclear tests, Able and Baker.

The Bravo shot was just one of 67 nuclear tests carried out by the United States in the Pacific Proving Grounds between 1946 and 1958. It was the first test in Operation Castle, a series of tests intended to evaluate different designs for high-yield devices in order to establish their suitability for weaponisation and production. Unlike the earlier Ivy Mike thermonuclear test, Bravo utilised a dry lithium deuteride with 40 percent content of lithium-6 isotope as its fuel source. This made it the first US deliverable fusion bomb.

The yield from the blast was estimated to be 15 megatonnes (equivalent to 15 million tonnes of TNT). By some accounts, this was two and a half times the predicted yield of 6 megatonnes. But by others, it was within the upper limits of what was predicted.

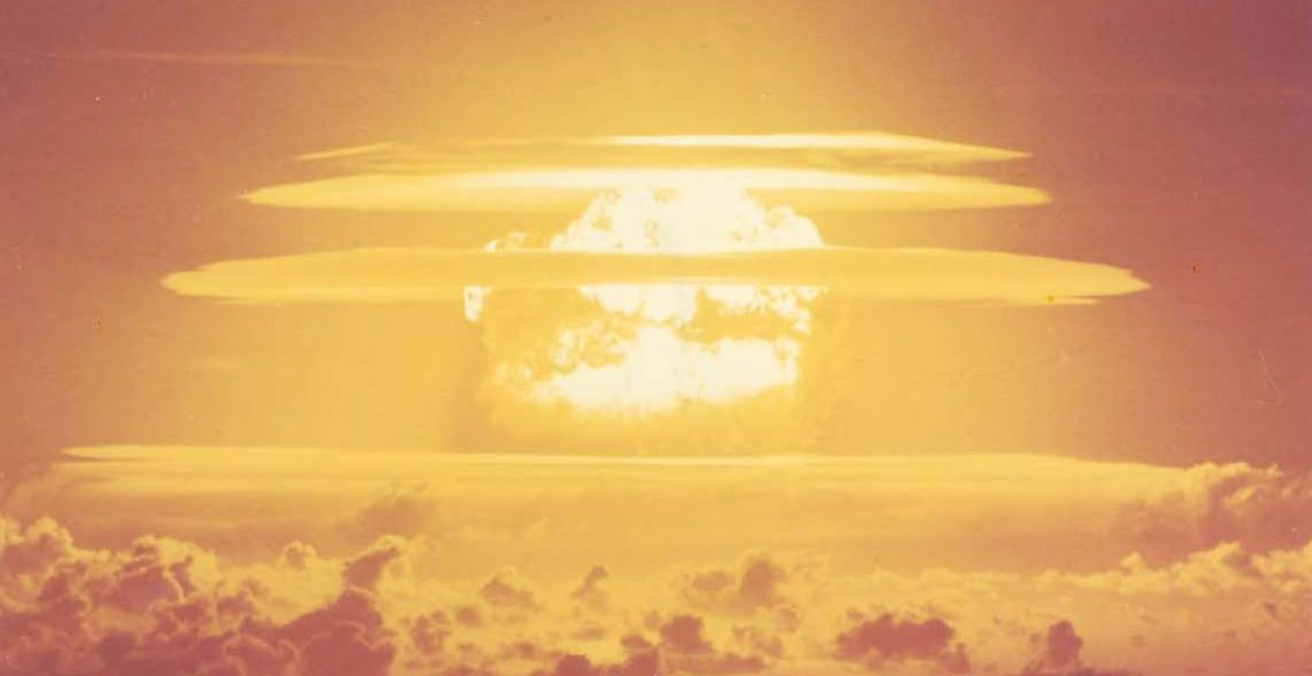

The blast from the Bravo test was immense. The force of the blast was described in a report written shortly after the test by Operation Castle’s military commander, Major General Percy Clarkson, and its chief scientist, Dr Alvin Graves. The test was reported to be so powerful the fireball from the blast grew within seconds to be “3 miles across.” Ten million tonnes of coral were coated with radioactive debris from the fusion reaction and sucked up into the rising fireball. According to Clarkson and Graves, the fireball rose to “45,000 ft in the first minute,” leaving behind a “4-mile wide stem of radioactive debris.” After five minutes, the rising cloud reached an altitude of more than “115,000 ft,” and after ten minutes the head of the mushroom cloud had grown to be “75 miles across.” It was from this giant cloud that the radiated dust drifted back down to earth and soon settled on nearby inhabited atolls, including Ailinginae, Rongelap and Utrik.

In contrast to the Crossroads tests, the Bravo shot was conducted in secret and with no attempts made to evacuate or notify the Marshall Islanders on the nearby atolls. Some commentators suggest the decision not to relocate them was based on standing orders from Washington to minimise costs, and that Bravo’s planners were confident the fallout would not affect the neighbouring atolls in the prevailing winds. Proponents of this view argue it was Bravo’s detonation at surface level that caused it to blast such large amounts of radiated coral into the atmosphere. And additionally, that there had also been a fundamental misunderstanding about the ability of the stratosphere to trap such debris.

However, much commentary takes the opposing view that there had been a change in the wind direction prior to the test and those in charge decided to just push on with it anyway, despite the unfavourable conditions. Some have even taken the more cynical view that the United States deliberately exposed the Marshall Islanders on the neighbouring atolls to the radioactive fallout in order to test its effects on human subjects. Adam Horowitz makes this argument in his film Nuclear Savage. Arguing that Project 4.1, which conducted tests on the affected Marshallese, was a pre-planned operation, rather than established retrospectively. Regardless of intent, it is widely argued the Project 4.1 tests were conducted without receiving informed consent and without much regard for the Marshallese.

Along with the other nuclear tests carried out in the Pacific Proving Grounds, the Bravo shot had a devastating impact upon the people and the landscape of the Marshall Islands. An estimated 665 Marshall Islanders were overexposed to radiation from Castle Bravo resulting in high incidents of birth defects and thyroid and other cancers amongst the population. The tests saw many people removed from their homes and parts of the Marshall Islands left uninhabitable. On Enewetak Atoll, another principal test site, the United States left the Runit Dome. By many accounts, this is a hastily constructed concrete lid built over a hole in the ground that was backfilled with radioactive waste. The Runit dome is reported to be leeching radioactive material into the surrounding sand and there are concerns that, like the rest of the Marshall Islands, it faces the threat of being submerged by climate change-induced sea-level rise.

It should be noted the Marshall Islanders were not the only victims of Castle Bravo. On the morning of the test, a Japanese fishing vessel “Lucky Dragon number 5“ (Daigo Fukuryu Maru) was exposed to the radioactive fallout approximately 145 kilometres downwind from the Bravo test. One of the fishermen died from radiation sickness on his return to Japan, while other members of the crew also fell ill. Coming just nine years after the United States dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, this sparked a major diplomatic incident and the United States eventually had to pay compensation to the Japanese.

In the 65 years since the Bravo test, the Marshallese have pursued various avenues to seek not only financial compensation for the damage done to their health, livelihoods and homes but also justice. In 1947, the Marshall Islands were made a UN trust territory under the administration of the United States. But in 1979, the Marshall Islands voted in a referendum to become a republic and in 1986 entered into the Compact of Free Association with the United States. The compact established a US $150 million fund to assist those who were affected by US nuclear testing. However, it has been widely criticised for being an insufficient amount and for only providing recompense for those affected by testing on the Bikini, Enewetak, Rongelap and Utrik Atolls, despite the damage being far more widely spread. Amendments were made when the Compact was extended in 2003, but these have not been sufficient to compensate the Marshall Islanders for the harm done.

Beginning in 2014, the former Marshall Islands Foreign Minister Tony de Brum led a bold attempt to bring attention to the global threat posed by nuclear weapons. De Brum attempted to take the nine nuclear-armed states to the United Nation’s International Court of Justice for failing to fulfill their obligations under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. This was ultimately unsuccessful but, arguably, it helped to bring greater attention to the plight of the Marshall Islanders.

While the United States was not the only nation to conduct extensive nuclear testing, they were responsible for 1032 of 2053 tests conducted worldwide. The former Soviet Union tested 715 devices, including the largest bomb ever detonated – the so-called Tsar Bomba in 1961.

Although much of the damage done to the Marshall Islands and its people is irreparable, there is perhaps some hope in the fact the attention the terrible events at Bikini Atoll have brought to the destructive nature of nuclear testing has worked to contain it. Although many years after it was first conceived the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty has still not come into force, it has arguably worked to establish international norms against nuclear testing.

Sean Walker is the Australian Outlook editor. He holds Masters of Journalism and Masters of International Relations degrees from the University of Melbourne and an MA (hons) degree in economics and philosophy from the University of Glasgow.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.