Can China use RCEP to Capitalise on Trump?

Trade Minister Steven Ciobo’s recent visit to China confirmed the end of efforts to revive the Trans-Pacific Partnership. The question is whether China can now capitalise on US protectionism by pushing through the multilateral Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.

Early last week, Australian Trade Minister Steven Ciobo ended the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) salvage mission. Travelling to Shanghai for the AustCham event, Ciobo pivoted from traditional TPP talking points to focus on the potential benefits of the China-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). With the spectacular collapse of the TPP, a renewed concern surrounding the role of the United States in global economic leadership has taken centre stage.

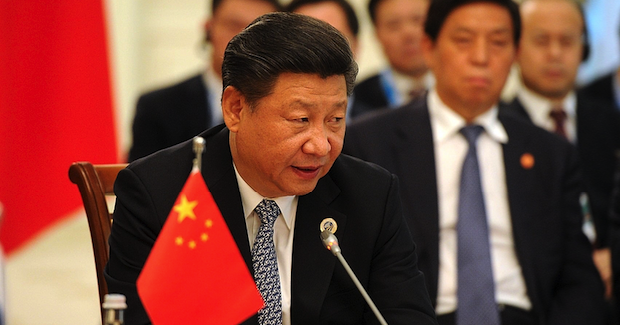

Over his first month, US President Trump has pulled out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), shown support for a Mexico border tax and has taken many positions on China and its currency manipulation. Counter to this, China’s Xi Jinping has used the first two months of 2017 to place himself in the public eye as the ‘anti-Trump’.

China: The globalisation reformer?

The World Economic Forum in Davos was China’s first salvo against Trump’s economic vision. During the event, President Xi Jinping conceded income inequality and lacklustre financial regulation were driving forces for the new wave of protectionism and isolationism. Yet in the tone of a reformist, Xi argued that “pursuing protectionism is like locking yourself in a dark room, which would seem to escape the wind and rain, but also block out the sunshine and air”. Seeking to play the role of a uniting and reforming world leader, Xi has begun to shift perceptions in a short space of time.

This reformist tone, unsurprisingly, has been warmly accepted by countries such as Australia. During the AustCham event, Minster Ciobo highlighted remarks from President Xi at Davos extolling the benefits of further regionalism and multilateralism, especially the benefits of RCEP for Australia. However, the shift from TPP to RCEP brings up an important issue: defining global economic leadership. There is no divine right or popular vote to elect a leader when it comes to international economic leadership.When Xi talks about globalisation reform or advises the US against walking away from the Paris agreement when they could “join hands in cooperation“, existing perceptions of who leads are challenged.

Going back to Bretton Woods, a new set of values were laid out for the post-war economic era. These values are based on the idea that cooperation and driving integration define global economic leadership. These values continue to foster perceptions to this day. Applying these values to the contemporary global economy, world leaders (including Australia) are currently presented with two choices: Do they continue to follow a potentially regressive protectionist/isolationist superpower in the US? Or, do they seek to follow China—a rising global power that professes a reformed status quo?

Critics of ‘reformist China’ such as John Pomfret argue that whilst China wishes to be seen as the leader of reformist globalisation and eschewing protectionism, the reality does not match opinion. Pomfret rightly raises questions about how China can be seen as the ‘anti-Trump’ by citing China’s protection of certain industries and economic rules that favour domestic companies. The idea that Xi’s China is becoming the ‘anti-Trump’ leader of the global economy dissipates when other countries hit the brick wall of Chinese mercantilism and protectionism.

From TPP to RCEP

However, with Trump having swiftly withdrawn from the TPP after taking office, China has been gifted an enormous opportunity to show its leadership credentials. The TPP was seen by many as a potential answer to what Jagdish Bhagwati called “termite” trade agreements. These are preferential trading agreements that have stacked upon each other over the decades leading to an economic trade system that some argue undermines negotiations at the multilateral level.

RCEP, as highlighted by Dr Jeffrey Wilson, is essentially an Indo-Pacific partnership wherein large-scale trade reform takes a backseat to more conventional—yet multilateral—tariff reduction negotiations. Whilst broader trade reform within RCEP could further help serve China’s goal of changing perceptions, China must now focus on completing the agreement.

In a longer report, Wilson lays out the path China should take. The RCEP must now be sold to its negotiating members as “the only practicable vehicle for multiateralising regional trade”. Only through the successful completion of the RCEP and continual appeal to the post-war values of cooperation and integration will China be able to successfully shift perceptions.

Steven Ciobo’s recent comments regarding RCEP show a blatant and resilient commitment to multilateral trade liberalisation policy in the face of US protectionism. However, China will be challenged by countries like Australia. In the AustCham speech, Ciobo raised concerns that the RCEP was lacking ambition. If China rushes too quickly to finalise the deal, or does not listen to negotiating members, the failure of the RCEP will severely hurt China’s and Xi’s leadership ambitions.

Throughout 2017, China biggest opportunity is also its biggest test. The question of US global economic leadership has been raised by countries like Australia and the opportunity to capitalise on Trump is in China’s hands.

Charles Bryant was the July-December 2016 international trade & economy fellow for Young Australians in International Affairs.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.