Can China Afford Its Global Ambitions?

China seems to be on the offensive everywhere these days. But as growth slows and budgets tighten, the country is finding it increasingly difficult to meet its imperial ambitions.

If the United States is perceived as the indispensable country, China has more recently become the unignorable one. The days when China kept a “low profile,” to use Deng Xiaoping’s memorable phrase, are long gone. That is especially true of Australia, which last month was the target of a 14-point ultimatum from China (to use the most natural word for it) demanding that Australia make a series of changes to its own internal governance relations, refrain from lecturing China on human rights, and somehow prevent individual Australians from criticizing China, too. The media seems to want to skirt the obvious by calling it a “list of grievances,” but the Chinese embassy’s “if you make China the enemy, China will be the enemy” appears as a clear statement of hostility. China may not be invading Darwin anytime soon, but seems to have placed Australia squarely within its sphere of influence — if not yet within its empire.

The twenty-first century Chinese empire now spans the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road,” extending as far as Luanda and Piraeus, however says nothing of Melbourne and Darwin. But running an empire is an expensive business, and it is unclear whether China has the funds to afford it. In theory, China is planning to build six aircraft carrier battle groups, ports in Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan, rail networks in Africa, secret submarine bases, new satellite networks, stealth jets, railguns, hypersonic missiles, quantum computers, and the list goes on. These developments are required to support its imperial ambitions, or in China’s preferred diplomatic language, its aspiration to “win-win cooperation.” All of this costs money, and money is always in limited supply, even in China.

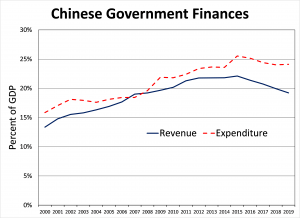

Four decades of rapid growth conditioned everyone, even Chinese planners, to believe that money was no object when it came to China. It may not be wise to trust official Chinese statistics, but according to those statistics, the average growth in Chinese government revenues between 1980 and 2015 was more than 15 percent per year. Shave off a few points for inflation, and it is still clear that money was pouring in at a prodigious rate. With that kind of revenue growth, it does not take much budgetary discipline to balance the books. Still, China rarely managed to balance the books. As in most countries, budget deficits were a way of life.

The difference in China is that, until 2015, revenue growth was so rapid that each year’s expenditures were superseded by the following year’s revenues. China had an endlessly expanding budget. Every year China would spend more than it could afford, but within twelve months, it could afford the prior year’s excesses. China’s leaders made ever-more extravagant promises — to neighbouring countries, to international organisations, to People’s Liberation Army generals, to everyone — because no matter how much they promised this year, they could always count on there being enough money next year to pay the bill.

For the last five years, however, China has been defaulting on its promises, if not exactly on its debts. It has demanded more local funding from partners for projects across Asia and Africa. Its six aircraft carrier battle groups have been downgraded to two. South China Sea islands have been built, then left to decay. Development banks like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the New Development Bank (or “BRICS Bank”) are lending far less than their authorised capital. Financial support for national champion technology companies has evaporated.

The effects can be felt as far away as Australia. Universities that set up think tanks and China centres in anticipation of a bonanza of official or unofficial Chinese funding have found it impossible to sustain their development programs once they had spent the official seed money. Chinese partner universities, once exploited as a source of research funding, now want Australian institutions to provide the funding for joint projects, for which the Chinese partners will contribute the staff. Budgets are tight all around. China is no longer the world’s piggy bank.

China is probably not going to go bankrupt anytime soon. But with an official government deficit running at about 5 percent of GDP (and expanding) even before the coronavirus hit, it is likely to be a lot less generous with international handouts from now on. And for China’s imperial “Belt and Road Initiative,” that presents a serious problem. Unlike the United States and other Western democracies, China has not founded its foreign policy on a community of common values, or even interests. China pays top dollar for its friends, who typically do not even accept Chinese Yuan. If China finds it can no longer afford to buy its friends, it may increasingly find that it has no friends.

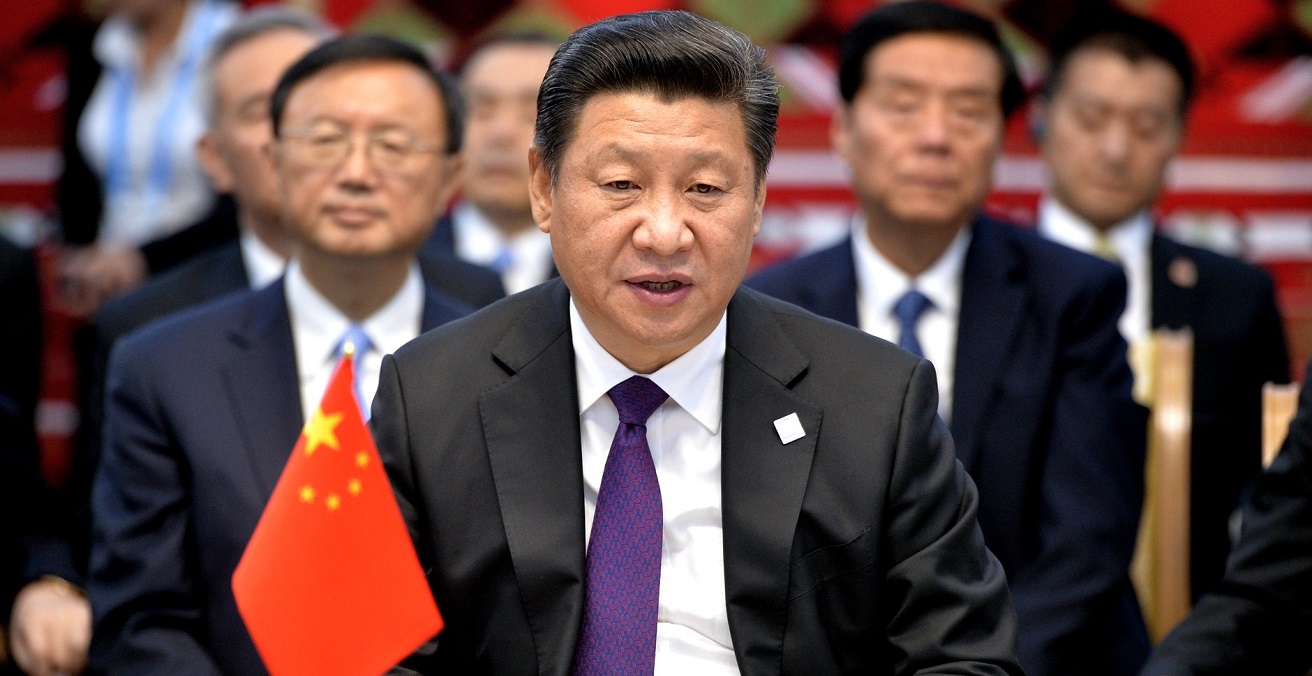

Xi Jinping clearly has global ambitions for China. However, he must meet those ambitions while acknowledging the declining budget of a highly corrupt middle-income country that has little to offer except money, which is exactly what he is running out of. Does anyone sincerely believe that China would have any friends among Australia’s economic and political elite, if it did not directly or indirectly subsidise them? On this basis, if you multiply that expenditure by several dozen, you can see how expensive the world looks when seen from Beijing. Double-digit growth rates can hide many structural weaknesses. Now that the economic party is over, the Communist Party will find it much more difficult keeping its “friends” onside — and holding its empire together.

Salvatore Babones is an associate professor at the University of Sydney and a fortnightly columnist for Foreign Policy magazine.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.