Bringing Space Age Politics Back to Earth

As the US, the United Arab Emirates, and China all celebrate successful arrivals of their Mars missions, it is worth observing geopolitical undercurrents. While the first space age of the 1960s was driven by Cold War politics, this new space age is fuelled by politics of the 2020s.

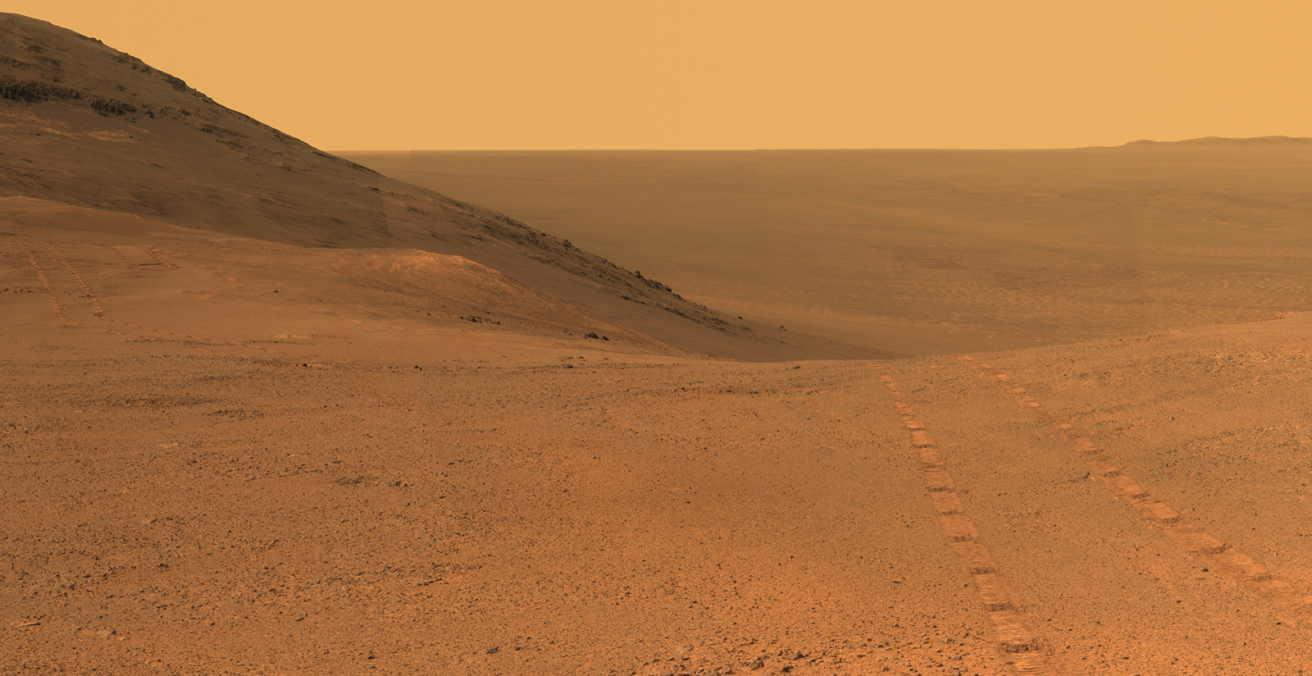

The ability to watch live stream images of NASA’s rover “Perseverance” landing on Mars was exhilarating. The crystal-clear pictures of the Mars-scape broadcast now almost daily on social media allow us all to feel we are a part of this exciting next step in inter-planetary exploration. As well, there is some international celebration of the United Arab Emirates (UAE)’s Mars orbiter “Hope” making a successful arrival – a first for any Arab nation – however, not as much media attention has been paid to China’s own recent Red Planet mission, “Questions to Heaven” (Tianwen-1). The intention of all three Mars missions is to gain more understanding of our neighbouring planet, with an eye to future human missions. But the geopolitics of these missions run deeper than their scientific purposes bely. The 21st century space age is highly competitive, and in the face of current tectonic shifts in global power relations, Australia would do well to have a better understanding of how politics are being played out in space.

As we read about the Mars missions, and NASA’s Artemis programme to return astronauts to the Moon for the first time since 1979, Australians can celebrate our their involvement in these exciting space initiatives. Since 2018, Australia has its own Australian Space Agency, whose mandate it is to support Australia’s space industry. Australia has signed the Artemis Accords, allowing Australian companies to be partners in NASA’s programme. Additionally, an Australian scientist, Abigail Allwood, leads the technology developed to examine Mars surface samples for signs of life. We hope to learn much from these scientific endeavours. Yet Australia should reflect on the political alliances and international competitions that are taking place underneath it all, to ensure it understands the implications of where it puts its technological, financial, and diplomatic support. To help, Australia can turn to the history of the 20th century space race.

The dawn of the space age was sparked by the Cold War. As the USSR and the US vied for technological and ideological dominance, their competition extended into space. With the launch of Sputnik in 1957, the USSR staked a claim to this “higher ground,” and the race was on. Both the Soviets and Americans rapidly developed space-based military intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance technologies, particularly to monitor each other’s nuclear programmes.

Already by 1958, the international community expressed concern regarding the potentiality of conflict between the superpowers extending into space. The United Nations (UN) was still a young and hopeful organisation, and the General Assembly adopted a series of resolutions urging exclusively peaceful purposes for activities in space. In 1959, the permanent UN Committee on Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) was established, with a mandate to ensure space diplomacy was at the forefront of activities in this new domain. Already by the early 1960s, the two superpowers and many of their allies were using space for telecommunications and broadcasting. The strategic importance of space had become a fait accompli.

Both superpowers began testing anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons, including nuclear explosions, but because the physics of space are so different from Earth’s environment, it was impossible to protect one’s own satellites from the impacts of activities intended to target one’s adversary. For example, the 1962 US nuclear Starfish Prime test took out British, American, and Soviet satellite telecommunications and affected radio transmissions from California to Australia. The competing powers realised if they wanted to ensure continued access to and use of space for their own national interests, they would need to put some restraining rules in place under international law.

Thus, at the height of the Cold War, two rivals negotiated and signed the 1967 Outer Space Treaty. The treaty gained immediate international support, possessing benefits for both the strong post-World War II allied powers and smaller nations alike. It remains the key treaty for all activities in outer space today.

The Outer Space Treaty has remained the cornerstone of space governance and international space diplomacy for more than half a century. While some critique it for lack of specific regulation, for instance on military or commercial activities in space, it was not designed to do this. Rather, it is a sort of constitution, laying down the ground rules of human expansion into space, which are still respected. One of the core principles is that space is not subject to appropriation: no country can claim ownership or sovereignty of any aspect of space. Another is that our activities in space should benefit all nations without discrimination.

These principles have prevented space from becoming subject to contested territorial claims, but they have not prevented geopolitical competition from extending into space. Just as during the Cold War, space is the technological domain where contestation and competition play out in the 21st century.

Today, there are many more nations active in space, and most of the world is dependent on space-based technologies for communications, internet, banking, navigation, tracking of weather, climate and natural disasters, and national security. Not only are more countries competing in the ability to access and use space, but half of all operational satellites orbiting the Earth are owned by commercial companies, most of which are US companies. And one third of all satellites belong to one company: SpaceX.

We need to think about our relationship to outer space the way we think about cyberspace. We all use it, need it, and should ensure the world has access to it. But not all countries have access, and we should be wary of the security implications and the economic interests which often outweigh international stability.

Our presence in space reflects our global realities. The bigger powers dominate space for commercial and military activities, and private entities dominate the economic and political climate. The creation of the US Space Force last year has raised tensions with respect to militarisation and potential weaponisation of space, as China, India, and Russia ramp up their space military programmes as well. China and the US are now in a race to return to the Moon, to begin mining resources for fuel and for long-term human habitation within the next ten years. Lessons learned in that race will be used to get to Mars, sparking new industries and new opportunities for particular ideologies to be carried into new human settlements. This is not science fiction, this is where countries and companies want to take humanity within a few decades.

Future space governance is likely to be a hybrid of states, international organisations, and commercial entities working together, which has exciting potential. What we need to ensure now is that Australia is nurturing partnerships with its non-traditional allies and not just pouring all resources into one programme with one partner. As global politics enter a new multi-polar reality, Australia needs to see its space activities as an extension of its Earthly political positioning.

None of the current Mars missions are an attempt to stake territorial or sovereignty claims, out of respect for the Outer Space Treaty. But they are expressions of technological prowess, which symbolise the ideological and political pride of each of the nations who have a remote presence there. “Perseverance,” “Hope,” and “Questions to Heaven” are all missions to ensure those nations have currency in the politics of the 21st century. Australia has a stake in greater collaboration and exchange of that currency, and with greater awareness, it could be playing a key role in space diplomacy.

Dr Cassandra Steer is a Mission Specialist with the ANU Institute of Space (InSpace), and a Senior Lecturer at the ANU College of Law. Her research focuses on space governance and space security, including space situational awareness and sustainability. She has published widely on the application of the law of armed conflict and use of force in outer space, including her recent work “War and Peace in Outer Space: Law, Policy, Ethics”, and has begun research on incorporating Indigenous knowledge into space governance. Twitter: @CassandraSteer.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.