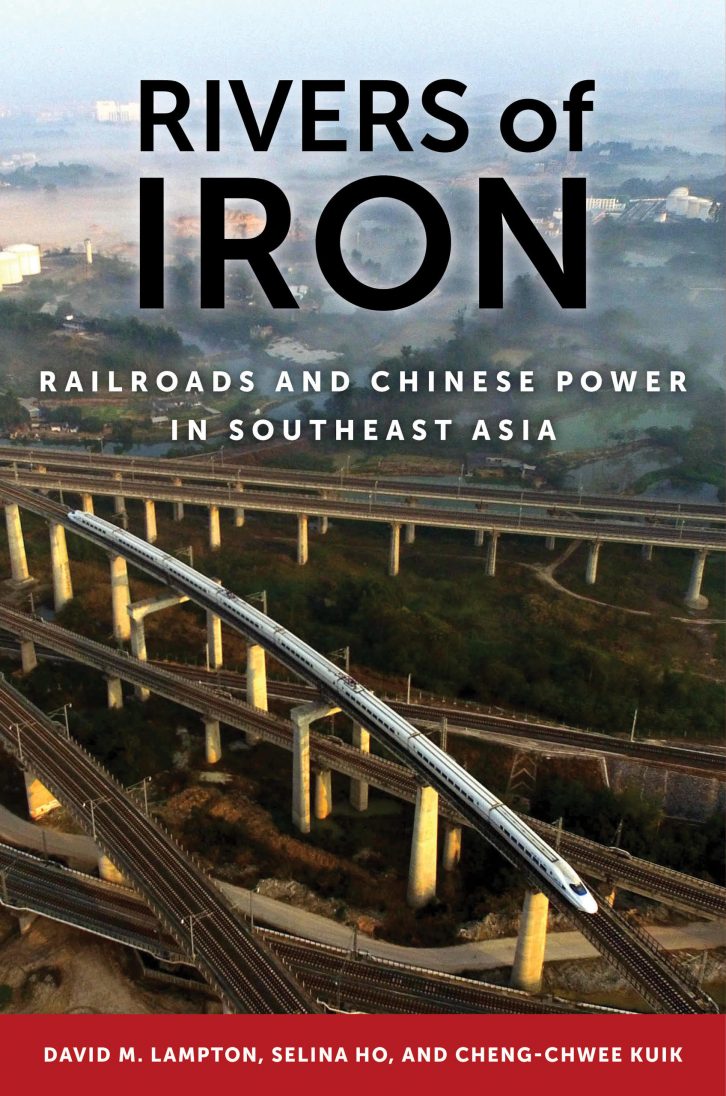

Book Review: Rivers of Iron - Railroads and Chinese Power in Southeast Asia

One part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative is a high-speed train project from Kunming, China through Southeast Asia to Singapore. This project suggests that China’s partner countries can have substantial agency and shape projects to suit their own interests.

According to a common narrative, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) would be brilliantly led from President Xi Jinping’s central control tower in Beijing. It is part of a grand strategy to establish a new regional order in Asia. So-called “debt diplomacy” and opaque loans are used to ensnare unsuspecting partner countries, and the benefits flow overwhelmingly towards China.

While there may be some element of truth in this narrative, the reality is much more complex and nuanced, according to Cheng-Chwee Kuik, David M. Lampton, and Selina Ho in their recent book, Rivers of Iron: Railroads and Chinese Power in Southeast Asia. Rivers of Iron documents forensic field work on one piece of the BRI, the project to build a high-speed railway from Kunming in China to Singapore, with three branches passing through Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam, then converging in Bangkok, before passing through Malaysia to Singapore. Apart from the segment crossing Laos, very little work has been done on the railway to date, with most segments still being discussed and negotiated.

The authors argue that the idea of connecting China with Southeast Asia by railways is not a new idea emanating from Beijing. Rather it is an old one, dating back to colonial times when the British and the French developed such plans, as did the Japanese during World War II. Following decolonisation, under Malaysian leadership, the countries of ASEAN (the Association of Southeast Asian Nations) put the idea to China.

It was only during the 2000s that China acquired the technological, engineering, and financial capacity to build high-speed railways in China itself, creating a competitive railway industry. By 2013, China was able to contribute to the vision of rail connections with Southeast Asia. In short, this is not a Chinese idea imposed on Southeast Asia. Southeast Asian countries agree on the importance of transport infrastructure for the future. At the same time, China’s assertive foreign policies are creating anxieties in Southeast Asia.

Despite China’s enormous system of high-speed trains, it is now facing numerous challenges developing this rail project with the seven different Southeast Asian countries. Each has their own different history, political system, and culture, which means that each reacts differently to China. The authors argue that these smaller neighbours are not devoid of agency as they are often able to influence, shape, and sometimes even manipulate China. Indeed, Vietnam, which has a long history of anti-China sentiment, has chosen to have only very limited involvement in the high-speed railway project, especially since an earlier Chinese light rail project in Hanoi was not successful.

The book highlights the importance of state capacity in determining negotiating power. Thus, Singapore, which is a very competent state and is not overly dependent on China, is well able to defend its interests, in contrast to the poor and landlocked Laos, which is a weak state. China also must deal with domestic politics in Southeast Asia. For example, when Mahathir Mohamad returned to the leadership of Malaysia in 2018, he was able to renegotiate railway deals, after having criticised his predecessor’s deals with China during the election campaign. Other challenges, like in Indonesia, are the impact on local populations, who may need to be compensated, and dealing with local authorities who were little consulted in the negotiations between Beijing and Jakarta.

In the case of the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway, Indonesia was able to play Japan off against China and extract a better deal from China with no sovereign guarantees and a lower interest rate. As all three railways from Kunming pass through Bangkok, Thailand has huge bargaining power with China, and it can readily exercise its mastery of balancing great powers.

China is also facing enormous technical challenges, notably in Laos, a very mountainous country, according to the authors. The high-speed railway through Laos requires 170 bridges and 72 tunnels to be constructed. What’s more, Laos has large amounts of unexploded mines remaining from America’s secret war in Laos. A Chinese railway engineer reportedly said, “we should have the United States demine the area.”

China is not alone in the Southeast Asian infrastructure space. Indeed, Japan has long been the leading infrastructure investor in the region, and in response to China’s BRI projects, Japan has stepped up its infrastructure diplomacy through its “Partnership for Quality Infrastructure” initiative. Indeed, missing out on the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway project has motivated Japan to compete more aggressively with China. There are also a number of other players like the US, EU, Korea, and the Quad active in infrastructure diplomacy.

The authors argue that the China which is involved in BRI projects is far from monolithic. The many Chinese actors involved include state-owned enterprises and banks, provincial governments, as well as different ministries in Beijing, all of which have their own pet projects. While Beijing may have a masterplan for this high-speed railway project, what actually gets built depends on these players on the ground. Interestingly, some of the greatest opposition to the BRI comes from Chinese academics and the public, who believe that China is wasting money on questionable projects.

Will China’s aspirations for high-speed railways connecting China with Southeast Asia succeed? The authors believe that the railway system will ultimately be realised, even if it differs in some details from the initial plans — already China greatly surprised the US by establishing its national high-speed railway. The authors also believe that it will be transformative, as were transcontinental railways in the US, with South China becoming the economic and strategic hub for Southeast Asia.

Rivers of Iron is part of a growing new literature which seeks to go beyond the hype of geopolitical rhetoric on the BRI and examine the reality on the ground. Another such excellent book is The Emperor’s New Road: China and the project of the century, in which author Jonathan E. Hillman shares with readers his journey observing BRI projects in Africa, Asia, and Europe.

According to all reports, the BRI is being slowed down and scaled back by COVID-19. But the BRI will likely remain a reality, especially as the Chinese government and companies are trying to be responsive to the many criticisms made, and are learning quickly. Thus, in this world where there is so much heat generated about China but much less light, Rivers of Iron shines a lot of new light on today’s China, and it should be required reading for all China-watchers and scholars.

This is a review of Cheng-Chwee Kuik, David M. Lampton, and Selina Ho, Rivers of Iron: Railroads and Chinese Power in Southeast Asia (University of California Press, 2020). ISBN: 9780520372993 (hardcover) & ISBN: 9780520976160 (eBook).

John West is adjunct professor at Tokyo’s Sophia University and executive director of the Asian Century Institute. His book Asian Century … on a Knife-Edge was reviewed in Australian Outlook.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.