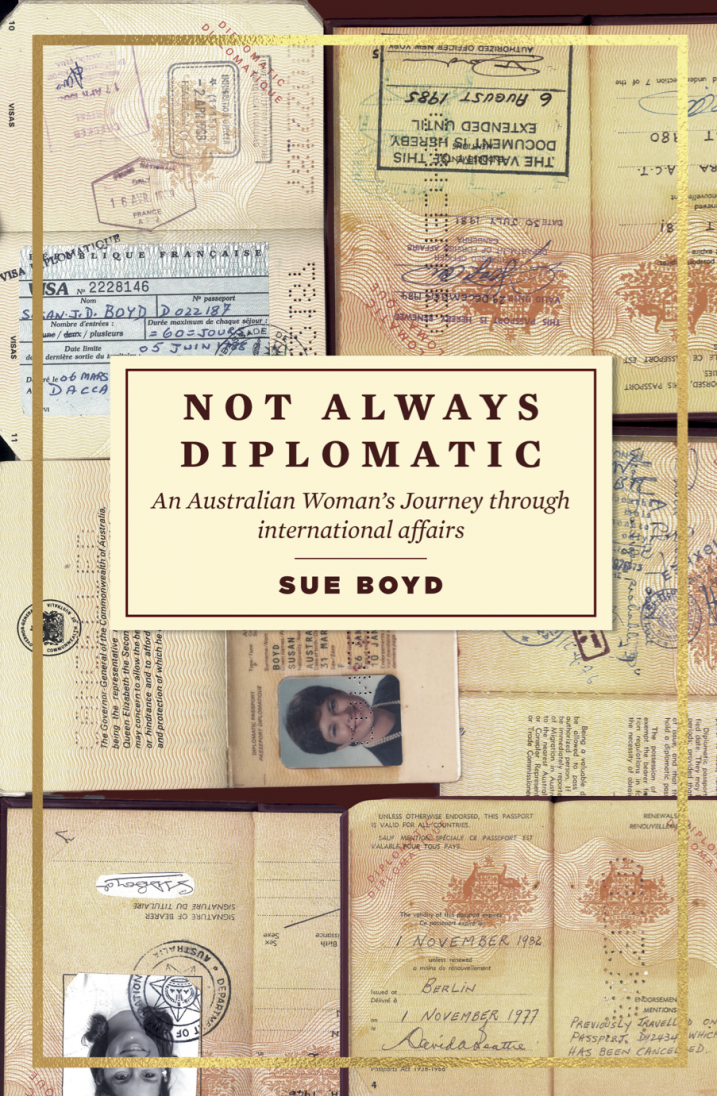

Book Review: Not Always Diplomatic

Sue Boyd was a trailblazing diplomat at a time when women were just starting to make a name for themselves in the Australian government. Her memoir provides a wealth of detail on the difficulties she faced and the substantial contributions she made to Australian international affairs.

As an avid reader, especially during our recent lockdown in Melbourne, I usually have two books on the go at the same time: a more serious one for spare moments during the day and a lighter one for “after hours.” But I found while reading Not Always Diplomatic that just one book sufficed. As Sue Boyd writes this “is not an academic analysis of Australian Foreign Policy. It is rather the view from the trenches from a career officer serving Australia’s interests internationally.” Although the analysis might not be academic, this book still gives us some important insights into what transpired in places where the author was posted – particularly in Fiji following the coup which took place in 2000. I don’t know whether Sue kept a diary, but throughout the book, the detail is impressive but kept at just the right level so that the narrative keeps moving. There is also a good dose of humour, sometimes at her own expense.

The subtitle to Not Always Diplomatic is “An Australian Woman’s Journey through international affairs.” As Peter Edwards says in an introductory comment, “Her engaging memoir should be read by anyone interested in a woman’s experience of what was, and to a lesser degree remains, a predominantly male profession.” A view of the current DFAT website reveals a vastly different picture to when Sue Boyd joined what was then the Department of Foreign Affairs in 1970.The department is now headed by a woman, Frances Adamson, and two of the five deputy secretaries are women. About a third of the listed overseas postings are now held by women, and in recent years, both the Foreign Minister and Shadow Minister have been women. But 1970 certainly was a different world to 2020.

The early chapters reveal an interesting family history. Sue did not start life as an Australian. She was a child of the British Raj, and as her father was in the British Army, she attended thirteen schools in five different countries. On leaving secondary school in England in 1964, she volunteered to teach in Africa for a year. In late 1965, she arrived back in the UK and found, to her surprise and fury, that her whole family was migrating to Western Australia. When told that she could attend the University of Western Australia (UWA), Sue wondered whether anyone had even heard of the place and whether her degree would have any worth. Sue seems to have fallen on her feet quickly, as she threw herself into life at the UWA. She was the first woman elected as president of the Guild of Undergraduates, defeating Kim Beazley, now the governor of Western Australia and author of the forward to this book.

Then her life took another unexpected turn. After only four years in Australia and still a British citizen, she bumped into a British friend, the son of the then governor of Western Australia, who told her that he had just been accepted as an Australian diplomatic trainee. At that time, the federal government was committed to improving gender balance, and this included the Department of External Affairs. Applications were closing the following day, but Sue was able to quickly organise her application, including a reference from the university vice-chancellor. So, in 1970 Sue moved to Canberra as one of two women in the departmental intake of 23. She also became an Australian citizen, although she retained her British nationality.

The young woman who arrived in Perth with her family in 1966 as “ten-pound poms” would never have dreamed that five years later, she would be posted to Lisbon as the third secretary at the newly created Australian Embassy. After several years there, she was back at a desk job in Canberra, though this was interrupted by being sent to Darwin to monitor developments in East Timor. Although Sue’s role in Darwin was important, she was quite rightly annoyed that she wasn’t sent to Dili, as the department said “if they sent a woman, the public would say that the government was not treating the situation seriously!”

Sue’s next posting was to East Germany from 1976 to 1979 where she was able to use the language learned at school in Germany as a child. In 2006, she applied to the German government to access her Stasi file, which amounted to 900 pages! Sue met many writers and artists in Berlin, although she found contemporary East German painting “on the whole dark and depressing.” However, the music was world class. Sue’s interest in art is apparent throughout the book, which includes illustrations of the artwork she sourced over many years and from all parts of the world.

After further postings to the UN in New York, Washington DC, and stints back in Canberra, Sue’s first posting as head of mission was to Bangladesh in 1986. Here she learned to play golf as she was advised that “most high-level decisions were made on the golf course.” This seems to have stood her in good stead throughout her later career. The descriptions of life in Bangladesh are fascinating on many fronts: geography, culture, religion, and the role of women.

Vietnam from 1994-1998 was, for Sue, “the best posting.” Here all her skills were utilised, and her interests fulfilled. Among other things, she was involved in discussions to open defence cooperation between Australia and Vietnam. Again, the narrative is enhanced by the personal stories, which are all well-chosen and enable the reader to understand what life is like as a diplomat living in a foreign country, including managing an embassy.

A subsequent posting to Hong Kong and Macau was not as appealing, although she was able to use her Portuguese language skills developed during her earlier posting to Lisbon. Sue was relieved to be posted as high commissioner to Fiji and other Pacific Islands, based in Suva, in 1999. Her friends in Hong Kong could not understand why she would be pleased to be posted to what they saw as a holiday destination, but she understood the importance of the South Pacific, where Australia had real work to do. The personal description of what transpired in Fiji at the turn of the century is as important as any academic analysis. The Speight coup of May 2000 started a crisis which lasted for 56 days. There were serious issues for Australia in how to handle the situation. Sue describes it as “one of the most stressful but most rewarding periods of my 34-year career in the Australian foreign service.” DFAT even received a report from a reliable source of a threat to Boyd’s life. Although the situation eased and elections finally took place in August 2001, tensions continued for some time.

Sue Boyd retired from DFAT at the age of 59 in 2003 and moved back to Perth where her family was still based. She joined boards and used her skills to mentor and coach people around the country. I first met Sue in Melbourne in 2004 when she was deciding whether to become president of the Australian Institute of International Affairs in WA. At that stage, she was somewhat reluctant to take up the challenge, but I was able to reassure her of the importance of the AIIA both in WA and nationally. She brought all her skills to the position during her eight years as president and was subsequently made a fellow of the AIIA for her contribution to Australia’s international relations.

Former Foreign Minister Gareth Evans has described this book as “An engaging account of life at the coalface by one of Australia’s most active and effective diplomats – and real pathfinder in leading our diplomatic establishment out of its sexist dark age.”

There is still work to do, but Sue’s story can provide inspiration to us all. The only criticism I have is that the book has no index.

This is a review of Sue Boyd, Not Always Diplomatic: An Australian Woman’s Journey Through International Affairs (University of Western Australia Press, 2020) ISBN: 978-1-76080-149-6

Zara Kimpton OAM is the National Vice President of the Australian Institute of International Affairs and a Past President of AIIA Victoria. She was the Leader of the Australian Delegation to the Women 20 (W20) Argentina in 2018 and the W20 Japan in 2019.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.